Environmentalism Is Antithetical to Abundance

From the Death of Environmentalism to the Abundance Movement

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

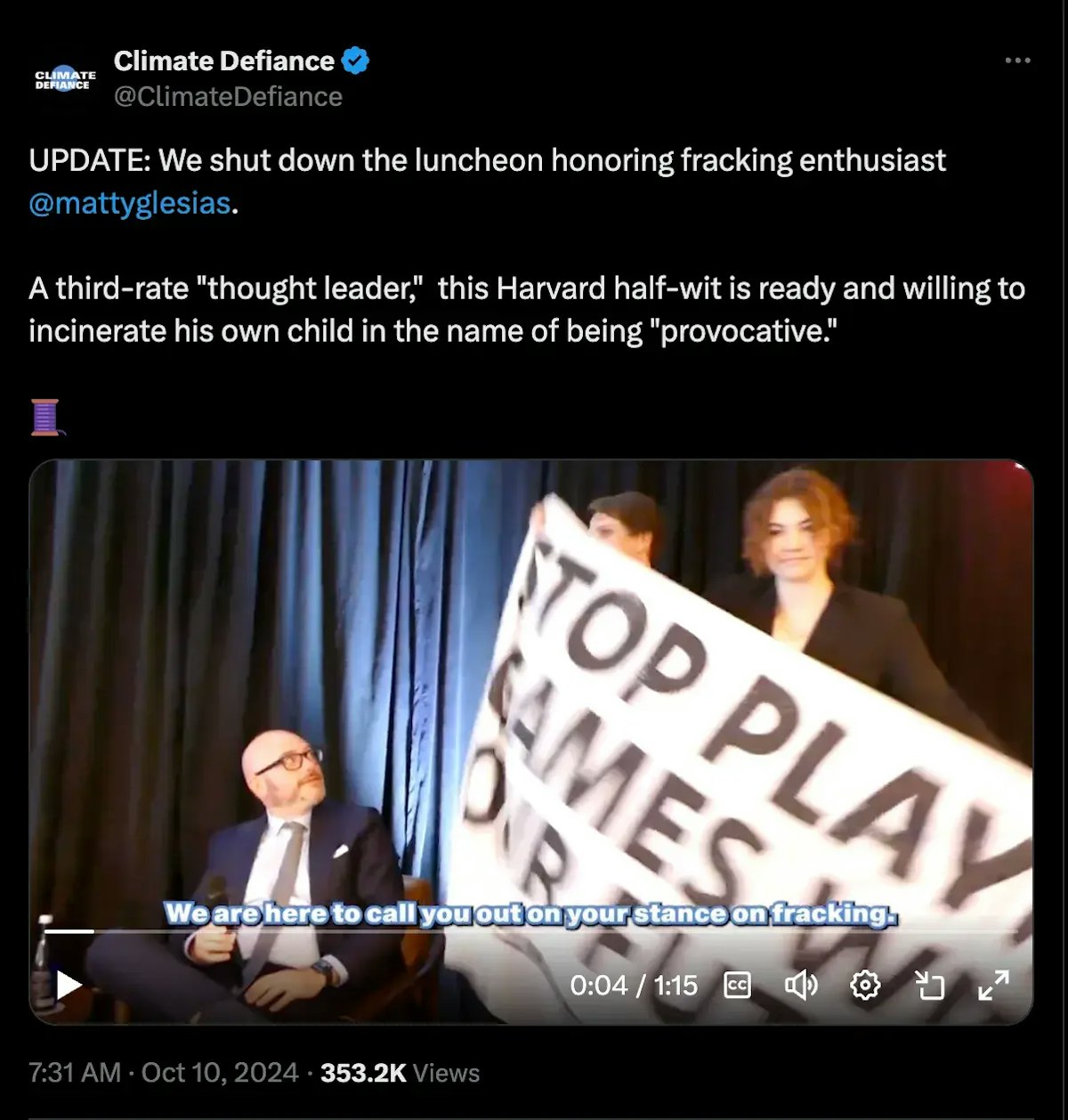

Every now and again, a series of events unfolds in such serendipitously perfect succession as to prove a point beyond any reasonable doubt. Yesterday, I gave a keynote at the first Abundance Conference in Washington, where I made the case that the climate movement is foundationally neo-Malthusian and, hence, the enemy of the Abundance movement. Shortly after I turned over the stage to Slow Boring’s Matt Yglesias and The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson to talk about the meaning of the Abundance Movement and its political future, the climate movement arrived to prove my point. Chanting “No Abundance with Climate Change,” “Yglesias Lies and the Planet Dies,” and “No False Solutions,” activists from Climate Defiance stormed the stage, shouted down the speakers, faked being “tackled” by a hotel employee, and brought the conversation to a halt for about 20 minutes. So perfectly timed was this demonstration of the methods and ideological commitments of the climate movement that many people in the audience initially thought that it was a prank that I had set up myself.

Lest anyone object that the group is not representative of the climate movement, it is important to note that Climate Defiance has been endorsed by Bill McKibben, Michael Mann, and Congressman Ro Khanna among many others and is funded by scions of the Getty, Disney, and Kennedy families and the Climate Emergency Fund, whose advisory board includes McKibben and New York Times columnist David Wallace-Wells.

As I have noted elsewhere, the climate movement increasingly aims not simply to advocate for its own demands for radical climate action but to silence more moderate, pragmatic, and nuanced viewpoints. It is hostile toward pluralism and the give and take of politics and negotiation that democratic governance requires and has become a far more influential source of science disinformation than opponents of climate action in recent years. As I will discuss in a forthcoming post, sooner or later, its tactics are likely to escalate to political violence.

You can read my remarks below.

From the Death of Environmentalism to the Abundance Movement

20 years ago this month, I published an essay called “The Death of Environmentalism” that anticipated the rise of the Abundance Movement. In the essay, I argued that modern environmentalism was incapable of solving climate change because climate change was, at bottom, not a pollution problem that could be solved by taxing or regulating carbon emissions. Instead, it was a technology and infrastructure problem that would require public investment in innovation.

That argument, I think it's fair to say, won the day over the last two decades. Indeed, if anything, there is growing recognition that not only is solving climate change not, centrally, a regulatory problem, but in fact it is a deregulatory problem. Innovating, building infrastructure, and deploying technology at the scale that it will take to effectively combat climate change will require reforming much of the environmental regulatory policy that the last generation of environmentalists established in the 1960’s and 70’s. So today, I want to talk about some of the key lessons from the essay that I think it is important for the Abundance Movement to keep in mind.

So first, let's take a quick walk down memory lane. Back when I published “The Death of Environmentalism,” the dominant view of the climate problem was that it was just a really big air pollution problem, acid rain on steroids if you will, that would be solved the same way that environmentalists had solved air pollution problems in the 1960s and 70s, by regulating carbon pollution.

The Death of Environmentalism said that was wrong, that climate change was not really an according to hoyle pollution problem at all. Carbon dioxide was not a trace pollutant resulting from a relatively small set of commercial and industrial applications. It was everywhere, completely intertwined with virtually every aspect of industrial modernity.

Because stopping the planet from warming requires that we stop emitting carbon dioxide entirely, that means that to effectively mitigate climate change, you have to build an entirely new energy economy. The essay argued that the modern environmental movement was spectacularly ill-suited—temperamentally, ideologically, and institutionally—to lead such an effort. A movement that centrally proposed to draw a circle around a thing called the environment, to speak for it politically, and protect it from us was simply not going to be serious about building the new worlds that we need to build so that both humans and the natural world might thrive.

In a lot of ways, the growing abundance movement reflects a broader recognition of this insight. I wouldn’t say that every part of the abundance agenda is a reaction to environmentalism. But a lot of it is—getting housing and infrastructure built in the face of NIMBY opposition, support for nuclear energy, advocacy for permitting reform, to name just a few examples.

Still, there is a view among a lot of people in and around the abundance movement that environmentalists should be our allies. We all care about the environment, after all, and we should be working together. And I stand here today to say that you are mistaken about that.

Why is that? Because an environmentalist is not simply someone who cares about the environment. Environmentalism does something more than that. It places a very particular idea about the environment at the center of its “ism.” In its modern incarnation, environmentalism proposes to situate humans inside a closed system called the environment, defined by fixed, biophysical, planetary boundaries, that humans must not violate.

So when you see the apparently bottomless commitment to proceduralism, stasis, and the regulatory state, the suspicion of growth, development and technology, and the opposition to nuclear energy, artificial intelligence, and genetic modification, these are not rogue impulses, or habits of mind that our friends in the environmental movement might be cured of. They are all quite central to the ideological commitments of the modern environmental movement.

In the cosmology of the movement, the earth system is completely closed. It contains all. Nature bats last, as Al Gore famously opined, and when humans transgress nature's limits, catastrophe and collapse ensue. Things like nuclear energy and genetic modification cannot be solutions to this problem because, definitionally, they transgress a natural order that humans have no choice but to submit to. Because fundamental natural processes cannot be modified without severe consequences, growth and abundance are impossibilities. Endless economic growth on a finite planet, as the saying goes, is impossible.

These views are, I think it's fair to say, irreconcilable with any recognizable notion of abundance. A closed earth system implies a closed human future. Environmentalism tells us ultimately that there is no alternative to stasis, to the steady state.

I’d doubt that there is a single person in this room who agrees with that sentiment. And thankfully, there is an alternative. About a decade ago, we at the Breakthrough Institute, along with some friends and fellow travelers, launched an alternative called ecomodernism. And you can pretty well tell the difference between ecomodernism and environmentalism by what each places at the center of its “ism. Ecomodernism places modernization, not the environment, at the center. It says that the earth system is not a closed system at all, it’s open. The earth was created from the detritus of exploded stars, bombarded by asteroids that brought water to our planet and turned it blue, and warmed by the fusion energy of a distant sun. Stasis is neither the past nor the future of either the earth system or the human species. Indeed, we have been modifying the Earth since before we were human. A planet that was capable of supporting perhaps a few million souls when we began our journey supports 8 billion of us today.

So while environmentalism tells us that we should run away from our technological and world making powers, ecomodernism tells us that we must run toward them, that the future of the planet, one that is better for both humans and nature in fact depends upon doing so. The fact that we in the abundance movement find ourselves on the other side of issues like permitting reform and nuclear energy from the environmental movement is not accidental. Because we are not allies. And while I believe that the Abundance movement should be a big tent, a place where there is plenty of room for Left and Right, Democrats and Republicans, even Marxists and Libertarians, there is no room in that tent for environmentalists.

You can join us in the fight to build a better world for humans and nature. A world where we mitigate climate change, protect biodiversity across the planet and everyone on Earth gets to live a modern life, with abundant food, energy, housing, and economic opportunity. But you have to check your environmentalism at the door. Because it is antithetical to abundance.