Has There Really Never Been An Energy Transition?

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

I’m not sure which is more annoying, talk among many clean energy advocates about an inevitable and unfolding energy transition, in which clean energy, primarily wind and solar, is displacing fossil fuels at large scale. Or insistence from many who style themselves to be hard headed energy realists that the world has never undergone an energy transition of any sort at all, pointing to the fact that global consumption of coal and even biomass are as high today as they have ever been.

The former confuses aspiration with analysis, substituting an “ought”—the belief that the rapid elimination of fossil fuels is necessary to avoid catastrophic climate change—with an “is”—the reality that despite much progress on technologies like wind, solar, and electric vehicles, fossil fuels remain stubbornly difficult to displace. The latter, expressed most recently in a recent issue of the Economist, strikes me as a “just so” argument that is narrowly true but broadly misleading.

To be clear, my allegiances, in general, are much more with the latter camp. Fossil fuels are quite remarkable in many regards. Abundant in the biosphere, energy dense, and easily transportable, they are deeply intertwined with virtually every aspect of modern life. Whatever progress the world makes towards getting off of fossil fuels won’t happen quickly.

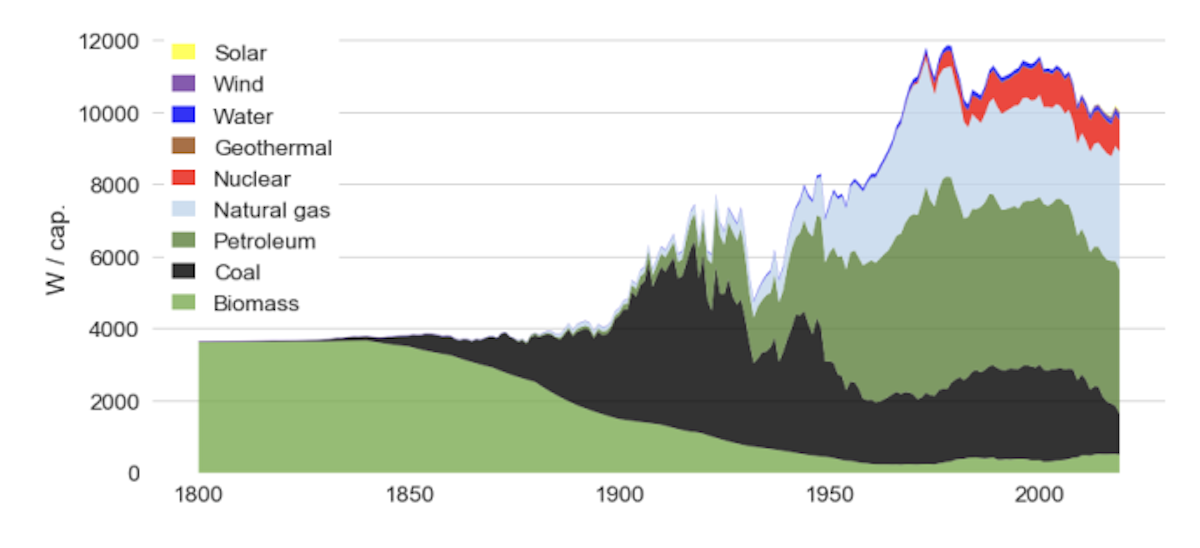

Still, the notion that the world has never undergone an energy transition and has simply added fossil fuels, along with a bit of nuclear and renewable energy, really misses the point. Yes, we still use as much coal and biomass for energy in absolute terms as we ever have. But we do so for a global population that is roughly 8 times larger than it was at the dawn of the industrial revolution and four times larger than it was at the beginning of the 20th century. As a share of global energy consumption, both coal and biomass have fallen precipitously. Biomass, in 1800, constituted virtually all global energy consumption. As late as 1900, it still accounted for just over 50%. Today, traditional biomass accounts for about 5% of global energy consumption, the vast majority of it in low income countries that have seen a lot of population growth over the last century but little economic development.

Meanwhile, many national economies have, in fact, transitioned almost entirely away from traditional biomass combustion. It has been many decades since biomass constituted even 1% of primary energy consumption in the United States, Britain, France, Germany, Japan, or any other high income country. Most middle income countries will soon follow suit. 430 million people in China shifted away from burning traditional biomass for home cooking between 2000 and 2020. Traditional biomass has fallen from 42% of India’s primary energy supply in 1990 to just 12% in 2020. Across Southeast Asia, old-school biomass had already shrunk to 14% of energy use in 2000 and has fallen to just 3% of energy consumption in 2023. In Latin America and the Caribbean, such forms of biomass have shrunk to just 4% of total energy demand.

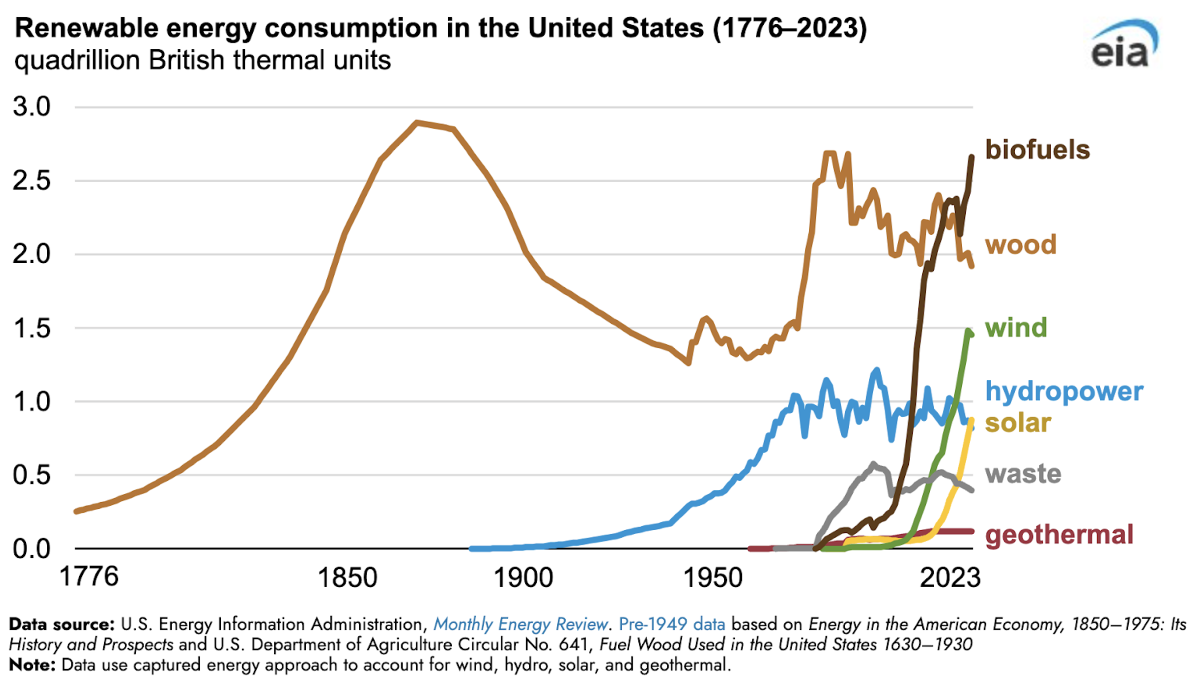

Modern sources of energy in all of these places are not simply augmenting biomass, they are replacing it. There remains a remnant level of wood burning in the US and other advanced economies, for fireplaces and woodstoves primarily. With vastly larger populations, these nations still burn wood at levels that aren’t that much lower than peak levels in the 19th century. But they do so not out of necessity but as a supplement to the modern sources of heating and cooking that for the most part meet everyone’s basic needs. Wood burning in rich countries is, for almost everyone, a luxury, not a necessity.

There is also the not insignificant issue of the growing use of biofuels. But again, biofuels use is best understood in most places as driven by rent seeking by politically powerful constituencies, not either an energy security or environmental necessity. The production and use of biofuels globally is basically irrelevant to the functioning of modern transportation systems. If all biofuel production went away tomorrow, it would not have any meaningful impact on global transportation costs or accessibility.

So the reality is that every advanced developed economy in the world has in fact undergone an energy transition and no longer meets its energy needs with biomass. Even with far larger populations and far higher per capita energy consumption, these nations have for all practical purposes entirely eliminated the use of traditional biomass for energy. Replacement of biomass for energy with fossil fuels and other sources of energy, along with vastly improved agricultural productivity thanks to fossil-based agricultural technology, is why forests in most industrialized nations are expanding—because those nations no longer use them for fuel.

The biggest reason that use of traditional biomass for energy in the global economy has increased in absolute terms is due to the fact that a share of the global population that is historically small in relative terms but nonetheless large in absolute terms continues to live in agrarian poverty. A billion people, give or take, lack access to modern energy sources and still use biomass as their primary source of energy.

This population does not use these fuels by choice. Biomass is free but not cheap, requiring substantial labor from those who depend on it to produce comparatively little energy with limited social and economic utility. But for the rural poor, with little or no formal income and living in subsistence economies that lack the institutions, infrastructure, and technology necessary to support modern energy consumption, it is the only option. There has been no energy transition in these regions because they have undergone little by way of modernization at all.

The science fiction icon William Gibson famously observed that “The future is here, it is just unevenly distributed.” The same is no less true of the past. Insofar as the world has failed to transition entirely away from biomass, the reason is due to a failure of development and poverty eradication, not because biomass has any particularly strong or tenacious hold upon modern energy economies. A future world that succeeds in eradicating extreme poverty will almost certainly also be one that has largely ended the use of traditional biomass for energy.

The story with coal is more complicated. There are still things, such as coking steel, that coal is uniquely useful for. But the long term trajectory is nonetheless similar. Globally, coal grew over the course of the 19th century to account for roughly 50% of global energy consumption in 1900, as the steam engine and subsequent iterations made coal essential for everything from mechanized transportation to manufacturing to lighting and electrification. Its spell as the largest source of global energy production lasted roughly 50 years, from 1910 to 1960. During that period, it never much exceeded 50% of global energy consumption, as newer fuels, mainly oil, were better suited to many old and new applications. Since its heyday in the first half of the 20th century, coal’s share of global energy consumption has fallen to roughly 25% today.

Coal remains king in many developing countries, accounting for almost 60% of total energy consumption in India and over 50% in China. But in most advanced developed economies, it is on the way out, accounting for 2% of total energy consumption in Spain and France, 3% in Great Britain, 8% in the United States, and 15% in Germany.

We often talk about the global economy as if it were a single thing. But all economies are predominantly local and regional. Traded goods typically account for 20% or so of national accounts. The vast majority of economic activity occurs within national economies, not between them. This is even more the case when it comes to energy. There is no global energy economy, only national energy economies, shaped by different macroeconomic forces, resource endowments, institutional and technical capacities, and national policies and often in the midst of very different stages of various modernization processes such as the demographic and agrarian transitions, urbanization, and industrialization.

There are, in short, no global energy transitions, only local and national transitions. In suggesting otherwise, skeptics who argue that the world has never undergone an energy transition make the same mistake as proponents who claim that the world is in the midst of one. Many of the latter point to the global growth of solar and wind energy in the aggregate and claim that these sources are growing faster globally than any energy source in the history of humankind. But these variable renewable energy sources, despite their rapid growth, still only account for about 6% of global primary energy consumption combined, barely half that of traditional biomass. At the national level, wind and solar together have yet to exceed 20% of primary energy generation in any major economy in the world. This compares unfavorably with both nuclear and hydro, which have achieved primary energy shares of roughly 30% individually in some economies and close to 50% combined. Indeed, as the chart posted above shows, in the United States wood and biofuels both continue to account for a larger share of total primary energy produced by renewable energy than either wind or solar energy.

The global trend, in this way, ends up obscuring far more than it reveals. Pointing to continuing use of biomass and coal globally tells us little about the nature of energy transitions for exactly the same reason. Biomass is irrelevant to the energy economies of all advanced developed economies. With continuing industrialization, alongside the demographic transition and slowing economic growth as national economies become more affluent, the use of biomass for energy globally will become increasingly rare. Coal use, likewise, has been virtually eliminated in a few advanced developed economies, is well below 10% of total energy consumption in many others, and appears to be close to a peak in China and globally in absolute, not just in percentage terms.

As noted above, how quickly coal declines globally is an open question. It is far more useful to modern economies than biomass. The primary way that advanced developed economies have eliminated the use of coal domestically for things like steel production and heavy manufacturing is not through replacing it with cleaner production methods but by outsourcing it to places that still burn a lot of coal, primarily China.

A transition away from oil and gas is even less imminent. Despite significant progress on electric vehicles, oil remains dominant in the global transportation sector, where its density and portability are unrivaled. The age of gas, as Jesse Ausubel has pointed out for many decades, is only at its beginning, not its end.

For these reasons, we are still many decades away from a full energy transition away from all forms of fossil energy in any advanced developed economy in the world, and still farther away globally, which is the subtext for a lot of these claims and counter-claims. But while it is one thing to observe that there is no sign of a transition away from oil and gas in the near or medium term, it is quite another to claim that an energy transition has never happened.