Energetic Africa

What Obama & the UN Should Do on Energy for Sub-Saharan Africa

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

The Obama administration, the US Congress, the United Nations, and other international agencies should encourage and plan for far-higher energy consumption in sub-Saharan Africa and in other regions that rely on burning wood and dung for energy, say a group of international energy and development experts in a new report, Our High-Energy Planet.

The report comes at a time of debate about how to help Africa and other poor nations gain access to electricity. Congress held hearings on Electrify Africa legislation in March, and the Obama administration is currently developing a framework to support increased electrification in Africa.

Today, over one billion people around the world — five hundred million of them in sub-Saharan Africa alone — lack access to electricity. Nearly three billion people cook over open fires fueled by wood, dung, coal, or charcoal. A recent report by the World Health Organization found that 4.3 million people die each year from household air pollution.

All nations need cheap and reliable electricity to develop. But in recent years, the authors say, the UN and others in the international community “have come to rely on small-scale, decentralized, renewable energy technologies that cannot meet the energy demands of rapidly growing emerging economies and people struggling to escape extreme poverty.”

Africa is set to increase the amount of electricity it gets from dams five-fold, and greatly expand how much of its oil and gas it produces. With larger reserves of natural gas than even the US, Africa today produces one-quarter as much as the US. About half of the gas African nations produce is sent abroad, while the US and Europe consume more oil and gas than they produce.

With Africa growing rapidly, the energy access targets set for Africa by the UN are far too low, the report authors say. “The UN’s flagship energy access program,” the report notes, “claims that ‘basic human needs’ can be met with enough electricity to power a fan, a couple of light bulbs, and a radio for five hours a day.”

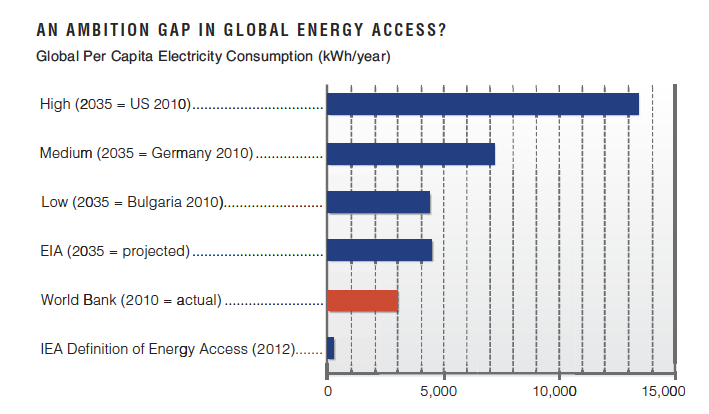

The report notes that the average European consumes that much electricity in less than a month. Similarly, the International Energy Agency (IEA) defines “energy access” as 500 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per year, or 100 kWh per person, which is about 0.5 percent of the levels consumed by the average American or Swede, or 1.7 percent of the average Bulgarian.

If the US and UN are going to both support development in Africa, and confront challenges like climate change, the authors say, energy access should be understood not as a charity for rural villages but as an essential component of national development. Cheap and reliable forms of modern energy are used to build roads, power tractors, create fertilizers, and power irrigation pumps, all of which improve agricultural yields and raises income. Affordable and reliable grid electricity also allows factory owners to increase output and hire more workers.

The report highlights the human side of electricity access. Electricity allows hospitals to refrigerate lifesaving vaccines and power medical equipment. It liberates children and women from manual labor. Societies that are able to meet their energy needs become wealthier, more resilient, and better able to navigate social and environmental hazards like climate change and natural disasters.

While there is no single or linear path to modern energy systems, the authors say, there is a common pattern. As countries move from agrarian to industrial to postindustrial societies, they transition from an almost total reliance on biomass fuels like wood and charcoal to reliable, grid-based electricity that relies on a mix of energy resources such as coal, oil, natural gas, hydropower, nuclear fission, and to modern renewables like wind and solar.

Technical innovation, economies of scale, government investments, and competitive markets for energy services improved the performance of these energy systems, lowered their costs, and enhanced the services they provide.

Climate change, the authors note, is a significant concern. However, it should not be dealt with by attempting to limit or restrict the energy consumed by the poorest people in the world.