Peak Coal in China or Long, High Plateau?

Half of Nation’s Power in 2030 Will Come From Coal

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

China coal power is one of the world’s largest single contributors to carbon dioxide emissions, which will likely need to be reduced to near-zero levels over the next few decades to manage climate change. So when two reports came out in the last few weeks that project a peak in Chinese coal consumption within the next couple of decades, many environmental and energy commentators concluded that the problem has been tamed, and that coal will be swiftly replaced by wind, solar and gas.

Unfortunately, a closer look at the findings refutes that conclusion. After China’s coal growth stops, the installed base of coal plants will remain, and that fleet will be the largest in the world—more than three times the capacity of all the coal plants in the United States. And unlike the US, most of China’s coal plants were built after 2000 and are young; they will operate economically for 40-60 years. New wind, nuclear, and solar plants in China will help at the margins, but the imperative need is to install carbon capture and storage (CCS) that can cut these plants’ CO2 emissions by 90 percent. Otherwise, the sheer size and remaining life of China’s coal fleet will make it impossible to achieve aggressive climate management targets.

The first report, by Bloomberg New Energy Finance last month, carried the hopeful title: “The Future of China’s Power Sector: From Centralized and Coal-Powered to Distributed and Renewable?” The key finding, as reported in the press, was that “renewables will contribute to more than half of new capacity growth and by 2030 installed renewable capacity will be equal to that of coal.” Bloomberg’s projections do show a great deal of new wind and solar generation over the next 15 years.

But the report fails to highlight that, at the same time as China renewables grow, the absolute amount of China coal fired generation will continue to skyrocket. According to Bloomberg, 343-450 Gigawatts of new coal generation will be built in China over the next fifteen years, more than the total capacity of the entire current US coal fleet, which is roughly 300 Gigawatts. Put another way, even in the Bloomberg best case, with the most aggressive solar and wind investments in the world, China will continue to bring on line roughly an average of one large 500 MW coal plant per week through 2030! This is on top of China’s existing 750 GW coal fleet, already more than twice the size of America’s.

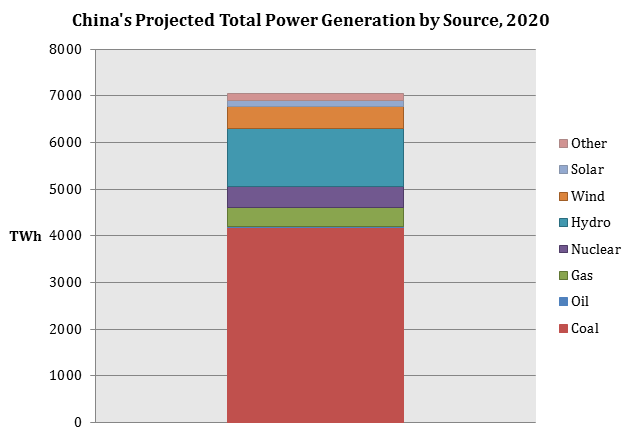

Furthermore, the report doesn’t compare the energy produced from all these sources. Because the sun doesn’t always shine and the wind doesn’t always blow, solar panels typically produce less than 20% of their peak capacity on an annual basis outside of the sunniest regions, and wind about 35%. By contrast, newer coal (as well as nuclear) plants in China typically produce at more than 80% of their peak capacity. Since China wind and solar have much lower capacity factors than fossil fuel plants, as well as nuclear, their 2030 contribution, especially on top of existing coal, will be relatively small even in the best case, as the figure below, drawn from the Bloomberg report data, shows — even assuming generous capacity factors of 25% and 40% for solar and wind, respectively. In all cases, including the most optimistic, well over half of China’s power in 2030 will come from coal.

Above: CATF depiction of China’s projected power generation by source in 2030, based on installed capacity figures contained in Bloomberg New Energy Finance, “The Future of China’s Power Sector: From Centralized and Coal-Powered to Distributed and Renewable?” (2013). Assumed capacity factors: Wind (onshore and offshore): 40%; Solar (utility and distributed): 25%; Gas and coal: 80%; Nuclear: 90%; Hydro: 40%. Fuel types excluded due to data unavailability from the source: geothermal, waste, biomass, solar thermal, oil. The share of offshore wind in the generation mix was estimated visually due to data unavailability from the source.

The second report, from Citigroup Research, titled “The Unimaginable: Peak Coal in China”, also received a lot of media attention when released early last month. The report points to a variety of trends in China – the drive for pollution reduction, general growth slowdown, slowdown in energy intensity of GDP, government support for nuclear and renewables, the potential for expanded gas use, and increases on coal plant and end use efficiency – which it suggests could moderate coal electric growth. It is worth, noting, though, that, under Citi’s stable economic growth scenario, coal generation continues to grow beyond 2020. Under two alternative scenarios, which received most of the media attention, coal generation either plateaus in 2020 or begins a modest decline.

As Citi acknowledges at page 26 of its report, these latter two peak scenarios embody a number of highly optimistic assumptions: that China’s growth in natural gas will result in 100 GW of new gas plants; that China’s nuclear development will hit its 2020 target of 58 GW; that GDP growth will not rebound to historic levels above 8%; and that renewables will be easy to integrate into the China grid at their current blistering development pace. Each of these assumptions can be challenged; for example, while it is widely hoped that abundant gas will lower the cost of new gas fired power plants, it is likely that any fracking revolution in China will take decades to develop – if the geology is suitable at all.

But, even indulging these optimistic assumptions, Citi’s “transition” case still shows that coal provides nearly 60% of China’s power in 2020, seven times more than wind and solar combined:

Above: CATF depiction of power generation, adapted from Citigroup Research, “The Unimaginable: Peak Coal in China” (2013), Figure 19, page 20.

In short, the China coal plateau is high. It is also likely to be quite wide and will dominate the China power landscape for decades. Why? Because coal plants are long-lived capital assets, typically with a 50-60 year accounting life, and the China coal plant building boom really only began a decade ago. By 2030, the vast majority of China’s coal plants will be less than thirty years old, with many decades of useful life left. Moreover, most coal plants being built today in China, unlike those in the United States, are highly efficient supercritical or ultra-supercritical plants. If air pollution remains a growing concern, China doesn’t need to bulldoze its newer coal plants; it can deploy relatively low-cost add-on scrubbers, which are already installed on many of China’s coal plants but reportedly underutilized. Unless renewables, nuclear or gas options materialize in China that are, on an all-in “greenfield” basis, demonstrably less expensive than the marginal costs of running existing coal units, they will be running for a very long time.

Whatever the story in China, it may be worse in other parts of Southeast Asia. The International Energy Agency reported recently that coal will replace natural gas as the dominant fuel for producing electricity in the 10 ASEAN nations, as the region almost doubles its energy consumption in the next two decades. ASEAN’s energy demand is growing at more than two times the global average rate, and 75% of the region’s annual new power capacity is coal, meaning more than 90% of its actual new power generation is coal based.

Which brings us to carbon capture and storage (CCS), a technology which separates carbon dioxide from coal and stores it deeply underground. This technology has been demonstrated extensively in the United States and has begun to scale up commercially here with a new plant under construction in Mississippi, and another permitted in Texas. CATF is also building partnerships between Chinese and US companies to demonstrate and scale up CCS in China and drive down global costs of the technology.

Without CCS applied widely in China, the nation’s coal fleet will remain the largest global clustered source of carbon dioxide emissions, with a “long tail” that could last for much of the 21st century – making most climate management plans, such as the “trillion ton cap” that was implied this month by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, nearly impossible to reach.

So, let’s celebrate the expansion of solar and wind and natural gas and nuclear in China, and the slowing of growth in coal generation. But let’s not let our celebration distract us from the need to directly address the multi-decade carbon emissions from China’s coal fleet as it exists today and as it will exist in 2020 and 2030. Advancing CCS for coal in China and elsewhere must be among the world’s top climate priorities.

This article originally appeared on the Clean Air Task Force blog and is reprinted with permission.

Armond Cohen is co-founder and Executive Director of the Clean Air Task Force, which he has led since its formation in 1996. In addition to leading CATF, Armond is actively involved in CATF projects focusing on Arctic stabilization, low carbon technology innovation and zero carbon fossil energy.

Kexin Liu is a research associate with the Clean Air Task Force, where he assists the Asia Clean Energy team with research and project coordination in facilitating partnerships between innovative energy companies across the Pacific to achieve rapid deployment of low- and zero-carbon coal-based electricity generation.

Photo Credit: News24x7.co