Defending Economic Productivity and Capitalism for Climate Adaptation and Mitigation - Part 2

Contrary to being a liability for adapting to and eventually solving climate change, economic productivity undergirded by private property, markets, and prices - is our primary asset.

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

In Part 1, I outlined the recent rise of the Degrowth Movement, where its supporters argue that the immense and urgent challenge of climate change necessitates the dismantling of capitalism and the deliberate reduction and redistribution of global wealth. I critiqued the Degrowth perspective for missing the critical role that economic productivity and technological progress plays in facilitating general climate adaptation. I showed that higher-income countries tend to be the ones that are most economically free and thus capitalistic, and it is these countries that are best suited to build infrastructure, respond to climate disasters, and have systems in place that are generally robust to our often hostile climate. I argued that capitalistic competition undergirds the technological innovation that causes direct climate adaptation, such as driving forward air conditioning, and supports the large tax base that produces nominally government-supported adaptation efforts like public infrastructure, early warning systems, and disaster response efforts.

In Part 2, I make the case that, just as capitalism is an asset for climate adaptation, it is also a key to transitioning to a sustainable low-carbon economy while simultaneously facilitating a high material standard of living.

Part 2: Mitigation of CO2 Emissions

One useful framework for thinking about drivers of global CO2 emission is the Kaya Identity, which breaks down human-caused CO2 emissions (from the energy system) into four fundamental components:

- Human Population

- Economic productivity (typically represented by GDP per capita)

- Energy efficiency of the economy (energy use per unit of GDP)

- Carbon intensity of energy (CO2 emissions per unit of energy).

These four terms are multiplied so, theoretically, if any one of them were to go to zero, then human-caused CO2 emissions associated with the energy system would also go to zero. Thus, we could eliminate anthropogenic CO2 emissions and largely halt climate change by reducing the human population to zero, economic production to zero, by magically producing goods and services without energy, or by harnessing energy without emitting CO2.

This last term is the only one that could plausibly and desirably go to zero. However, the Degrowth Movement also heavily emphasizes putting downward pressure on all the other terms, especially economic productivity driven by capitalism. This emphasis is not without some logic because, historically, global CO2 emissions have been increasing, and they have been driven up primarily by an increase in population and economic productivity (this is despite increases in energy efficiency and reductions in carbon intensity of energy).

However, attempting to force down economic productivity in order to reduce CO2 emissions is parochial and misguided because it is actually economic productivity itself that puts downward pressure on all the other terms, making a sustainable society more plausible in the long term.

Let’s look at this in more detail, going through the four terms one by one.

Population

In order to achieve an indefinitely sustainable society on earth, it is fair to argue that the human population would need to stabilize at some level. Some environmentalists have long advanced the notion that the human population will increase exponentially as long as it has resources to consume, much like bacteria in a petri dish. In this model, population can only be stabilized through the blunt force of running out of resources, or it can be stabilized preemptively via top-down coercive policies that discourage reproduction.

But this model is wrong. Humans do not simply multiply uncontrollably until they consume all resources. In fact, It turns out that as societies become materially better off, fertility rates tend to decline naturally. This phenomenon apparently results from a multitude of factors associated with economic productivity, including increased access to education, especially for women, improved healthcare, and reduced child mortality rates. But capitalism has also played a more direct role as it is the most decentralized and capitalist economies that tends to have the lowest fertility rates.

One reason for this is that in capitalist systems, women have far greater motivation and incentives to invest in their human capital or career prospects. The disproportionate purchasing power that results from disproportionate investment in professional development motivates many women to prioritize careers over having larger families.

In addition to cultural drivers, the more proximate mechanism that greatly facilitates lower fertility rates—birth control largely in the form of oral contraception—has been driven forward by capitalism. The first birth control pill, Envoid, was developed in the 1950s by the G.D. Searle & Company. Since the introduction of Enovid, innovation in contraception has continued to advance as pharmaceutical companies have developed lower-dose birth control pills with reduced side effects. Bayer and Merck have developed IUDs that compete with birth control pills, and recently, there has been innovation in non-hormonal options, male contraception, and digital health technologies for tracking fertility. These innovations were not the result of a government mandate or concern for the environment, but rather resulted from private firms correctly identifying market opportunities to generate profit.

Energy Efficiency of the Economy

Increasing the energy efficiency of the economy means using less energy to produce the same amount of economic output, and this can be achieved through technological advancements, more efficient production processes, and a larger share of GDP coming from services rather than physical goods.

In a decentralized capitalistic economy, private firms seek to maximize profits by competing to offer goods and services at the lowest possible price. In this system, a penny saved is a penny earned, so a key lever for increasing profit is to reduce input costs to the production process. Since energy costs money, firms have an incentive to reduce direct energy expenditure as well as the embedded energy in the physical inputs to their production process. Furthermore, consumers have an incentive to demand products that are energy efficient. Nobody wants a TV that will double their monthly electricity bill.

The story of the modern smartphone, summarized by Andrew McAfee in More from Less, demonstrates this phenomenon. He highlights that the smartphone is a single compact device that replaces 13 out of 15 devices advertised in a 1991 Radio Shack ad.

This consolidation represents not only a reduction in physical materials, but also in the energy required to produce these services–not to mention the simultaneously increased quality of the services. Additionally, the brick-and-mortar RadioShack itself has been put out of business by more efficient means of shopping for and obtaining these services.

The creative destruction of all of these now-obsolete devices, and their retailer RadioShack, was not driven by a top-down mandate on energy efficiency, but rather by entrepreneurs like Steve Jobs (in the case of the smartphone) and Jeff Bezos (in the case of the demise of RadioShack) operating in a competitive capitalistic environment that demands innovation in efficiency.

These dynamics even foster reductions in energy use via the reuse of goods. Profit-seeking companies like Facebook have developed services like Facebook Marketplace that greatly facilitate the transfer of items between individuals, effectively extending their lifetimes and reducing waste and the demand to create new items.

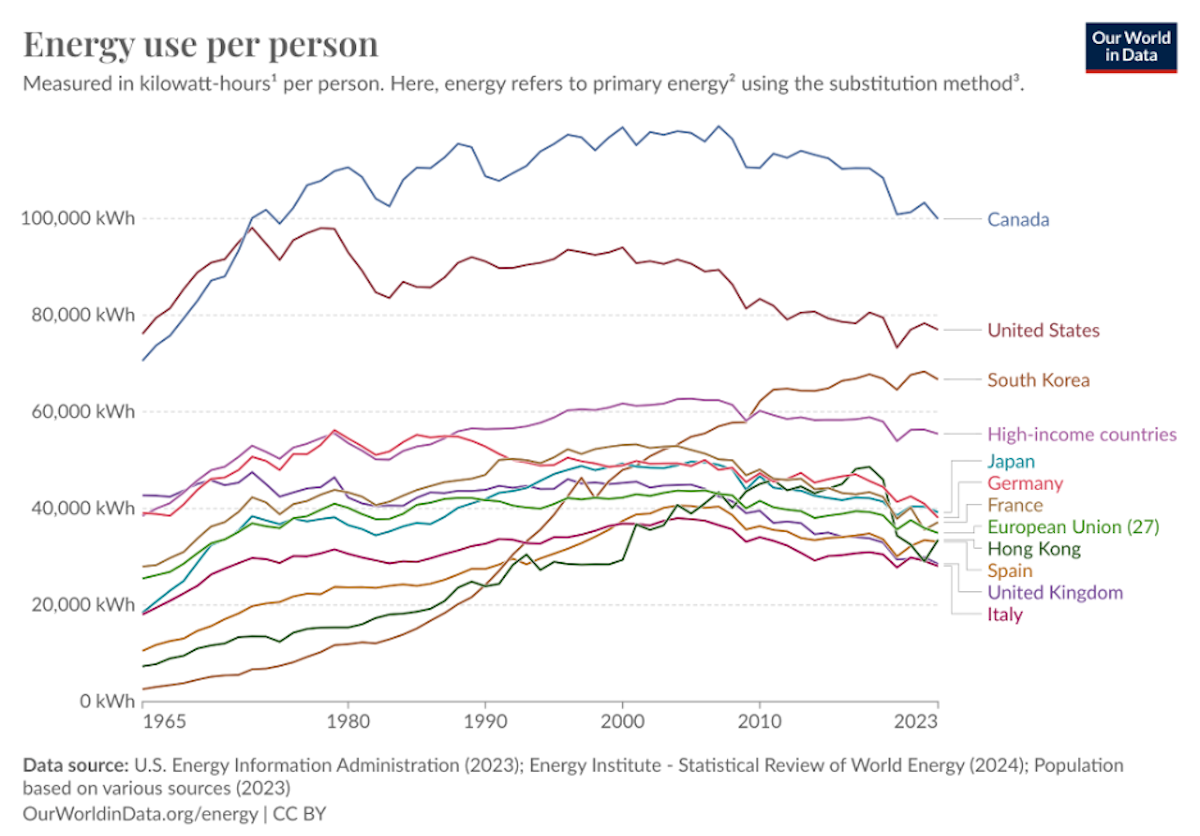

The above are specific examples, but they are representative of broader trends observable at the aggregate economic level. In the highest-income countries, which also tend to be the most economically free, we have seen peaks and subsequent decreases in energy consumption not only per unit of GDP, but also on a per-person basis.

The motivation for creating the iPhone, Amazon, Facebook Marketplace (as well as the motivation to participate in Facebook Marketplace), and widespread efficiency innovations across all sectors of free capitalistic economies is not primarily a desire to reduce environmental impacts. Yet, the result has been an increase in efficiency so great that many more people have access to much higher-quality goods and services, even as absolute resource and energy use has decreased.

These innovations came about from people acting in their own economic self-interest within an institutional environment where private property and freely fluctuating prices signal supply and demand and, thus, the most efficient use of fundamentally scarce resources. Therefore, this progress comes about because of, not in spite of, economic self-interest. Yet in top-down communist regimes advocated for within the Degrowth movement, these price signals and economic self-interest would be abolished or severely thwarted, relying instead on technocratic control of production through coercion. As examples like the Soviet Union, China in the middle of the 20th century, North Korea, East Germany, and Venezuela have shown, this has historically proven to result in tremendous inefficiencies and a lack of incentive to innovate.

Carbon Intensity of Energy

Carbon intensity of energy can be reduced by deploying carbon capture and storage technologies and shifting from burning fossil fuels to energy sources like nuclear, hydro, wind, solar, and geothermal. Carbon intensity of energy is the only term in the Kaya Identity that could plausibly and desirably go to zero, and thus, it must play a central role in the discussion.

Global carbon intensity of energy has been decreasing gradually since the 1960s. The overall environment in which this is fostered is summarized in More from Less as having the four elements of 1) capitalism, 2) technological progress, 3) an informed public, and 4) responsive government. Publicly funded science led to the discovery and subsequent public awareness of the climate change problem, which in turn has led to democratically elected officials implementing government policies supporting R&D and commercialization of energy technologies that reduce the carbon intensity of energy. Ultimately, however, the technological progress necessary to offer low-carbon energy at affordable prices is and will be driven by capitalism.

In competitive capitalistic environments, energy producers attempt to reduce costs and improve efficiency to improve their prospects of securing government contracts and partnerships with utilities. Venture capitalists, motivated by the potential for high returns, fund these efforts, betting on various technologies' potential to meet future energy demands. As Thomas Friedman eloquently put it, “It's very hard to get a generation living today to make major sacrifices for a generation yet to be born, and that’s why you also need the profit motive.”

Examples of these dynamics abound. In wind energy, companies like Vestas, General Electric, and Siemens Gamesa are racing to produce turbines that capture more energy from the wind while reducing the cost per megawatt-hour (MWh).

In solar energy, companies like First Solar, LONGi Green Energy, and JinkoSolar are battling to produce ever-cheaper and more efficient panels. Even though it is in tension with the core ideology of the Chinese Communist Party, the Chinese-based solar industry has embraced a for-profit model where private firms compete against each other in order to motivate innovation.

Advanced geothermal energy is characterized by rapid innovation from companies like Fervo Energy, which uses horizontal drilling to access new resources, and Eavor Technologies, which developed a closed-loop system that eliminates the need for natural underground water reservoirs. TerraPower, Kairos Energy, and X-Energy are examples of competitors in advanced nuclear reactors, vying to create smaller, safer, and more efficient designs.

These innovations extend beyond just energy. Companies like CarbonCure (which injects captured CO2 into concrete for permanent mineralization) and Solidia Technologies (which cures cement with CO2 instead of water, cutting energy use and emissions) are competing to reduce the carbon footprint of cement production. Similarly, the electric vehicle (EV) industry features intense competition among Tesla, Rivian, and Lucid Motors. Rivian, backed by Amazon, emphasizes electric trucks and SUVs, while Lucid targets the luxury market with its Air sedan. Ford's Mustang Mach-E and F-150 Lightning, alongside GM's electrification plan for 2035, demonstrate traditional automakers striving for market share in the EV sector.

Just like in the realm of energy efficiency of the economy, competition for market dominance, funding, and contracts—driven ultimately by the profit motive—is responsible for producing the innovation we see in clean energy. And this explains why the most decentralized and capitalist economies tend to have the lowest carbon intensities of energy.

Economic Productivity (GDP per capita)

The last term on the Kaya Identity that we will investigate is economic productivity or GDP per capita. As we saw in Part 1, higher economic freedom is associated with higher economic productivity.

Societies characterized by elevated levels of economic freedom and productivity are largely responsible for fostering the technological innovations that enhance the energy efficiency of the economy while simultaneously reducing the carbon intensity of energy. A high material standard of living is a prerequisite for the aforementioned innovations, as it allows for human energy to be directed towards these higher-level goals rather than being exclusively focused on meeting basic material needs. However, after a certain standard of living is achieved, further GDP growth can be achieved while simultaneously reducing CO2 emissions (an example of the Environmental Kuznets Curve).

In the United States, for example, CO2 emissions peaked in 2007 and have been on a downward trend since, despite continued productivity growth. The US is not alone in this pattern and is one of at least 30 high-income countries that have achieved economic growth while reducing CO2 emissions in recent years.

Once a technology has been invented, it can be widely adopted without being invented again. Thus, groundbreaking ideas and innovations have widespread and lasting consequences, and it is in humanity’s best interest to maximize our collective ideas. There is more than sufficient reason to alleviate poverty for its own sake, but an additional benefit of poverty alleviation is that it will liberate billions of minds from solely focusing on the basic necessities of life. Some of those minds can then contribute to innovations in energy efficiency and zero-carbon technology, greatly expanding the possibilities of breakthrough technologies that might be adopted globally to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In this sense, there is no reason to believe that global economic productivity is currently “sufficient.” Furthermore, as we have seen, economic productivity is critical for putting downward pressure on the three other components of the Kaya identity: Stabilizing population, increasing energy efficiency, and decarbonizing the energy system.

But economic productivity also seems to have breaks built into itself. Contrary to a prime argument advanced by the Degrowth Movement, the capitalistic system that undergirds economic productivity growth does not inherently require endless growth. As Harry Saunders has shown, growth is not a tenet of capitalism in any formal mathematical sense, and in the real world, we observe that once societies reach a certain level of productivity, their growth rates actually begin to decline.

If human appetites for goods and services were insatiable, we would see the highest-income countries having the highest growth rates. But as people become materially better off, they choose to work fewer hours, effectively sacrificing purchasing power and consumption for leisure time. This allows for GDP growth itself to slow without top-down coercion from a centralized authority.

Conclusion

Within the Degrowth Movement, it is presumed that if humanity is left to its own devices, decentralized economic activity will result in ever-expanding resource extraction rates and ever-expanding greenhouse gas emissions. Thus, the supposed solution is to centralize control of the global economy in order to force people (ultimately through coercion) to not engage in transactions they want to engage in. Public Choice theory explains why it is a serious error to assume that a global state, given centralized control of the economy, would act in a way that optimizes social outcomes. Those in government, just like those outside of it, tend to act in self-interested ways. When control of the economy is centralized, efforts of the ambitious and talented tend to go towards gaining political power or favor with those in authority, rather than on out-innovating competitors in the markeplace.

This is ultimately why capitalism is so successful, not only at increasing productivity overall, but also at facilitating climate change mitigation: it channels natural human self-interest in a way that is socially beneficial. These benefits are relatively straightforward and intuitive in the realm of climate adaptation, but we see here that they also extend to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Specifically, private property, markets, and prices actually work to reduce fertility rates, improve energy efficiency, and reduce the carbon intensity of energy. Thus, decentralized economies do not inherently result in indefinite climate change, and instead, they may be the best system available to stabilize the climate while supporting the continued improvement of human welfare.