Do Climate Adaptation Strategies Get Enough Attention?

The Case of Wildfires in California

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

Wildfires in California have taken center stage once again in 2025 and have inspired diverse arguments about wildfire causes and, thus, potential solutions. The influence of climate change often takes center stage in such discussions, even if it takes attention away from more immediate on-the-ground adaptation strategies that have a much more direct impact than greenhouse gas emission reduction policies.

Proactive fuel reduction treatments such as mechanical thinning and prescribed burning are one such adaptation strategy relevant to wildfires in California and western North America more generally. These treatments aim to reduce fuel loads to lower fire intensity and severity, thereby reducing their impact. We know that these treatments work under most circumstances, but thus far, there has been little research on whether these strategies work well enough to make a major difference as the climate continues to warm.

We recently published research focusing on just this question and found that there is substantial potential for fuel reduction to reduce wildfire intensity in California even as it continues to warm:

- Brown, P.T., Strenfel, S.J., Bagley, R.B., Clements, C.B. The Potential for Fuel Reduction to Reduce Wildfire Intensity in a Warming California (2025). Environmental Research Letters, 10.1088/1748-9326/adab86

I recently gave a short technical presentation on this research at the American Meteorological Society’s annual meeting and a longer, less technical presentation at Columbia University.

Background

Fire activity in western North America and in California used to be much more prevalent than it is today and probably reached a long-term minimum in the latter part of the 20th century.

Below is a record of fire occurrence from Swetnam et al. (2016) for a network of more than 800 sites in western North America, which shows the precipitous decline in fire frequency starting at the end of the 19th century.

Similarly, the findings of a more recent and more comprehensive paper, Parks et al. (2025), are summarized in the schematic diagram below that tells the same story:

As you can see in the above figures, fire activity hit a trough in western North America but has been ticking up over the past several decades. Perhaps ironically, one of the main causes of the current increase in fire activity is the antecedent decrease in fire activity caused by humans. The photos below from Graham et al. 2004, illustrate what is going on.

Prior to European colonization, indigenous people, along with natural fire regimes, had historically caused fires to occur roughly once per decade in many forests in western North America. This continuously cleared out much of the surface vegetation and smaller trees to the point where covered wagons could routinely traverse these forested landscapes when the Europeans arrived. However, by 1912, the US federal government halted these practices entirely, and in 1935, the “10 a.m. rule” was introduced, requiring that all fires be extinguished by 10 a.m. the following morning. This fire exclusion was initially successful but led to a buildup of vegetation, or “fuel,” in the forests. The map below, from the California Wildfire Taskforce, shows that much of the Sierra Nevada region in California, for example, has not seen fire in over 70 years, which is a major departure from its traditional fire frequency.

Once continuously warmer and drier conditions arrived on top of this fuel buildup, fire exclusion became less effective, and fires became more difficult to contain, leading to an increase in catastrophic uncontrollable fires since the 1980s.

The potential for fuel reduction to reduce wildfire intensity in a warming California

So, what’s the solution? One key approach is to bring conditions back to something closer to where they were in the 19th century by intentionally setting fire to the landscape under favorable conditions and also removing fuel mechanically. This results in less fuel to burn when wildfires occur, making them less severe and easier to contain.

Once continuously warmer and drier conditions arrived on top of this fuel buildup, fire exclusion became less effective, and fires became more difficult to contain, leading to an increase in catastrophic uncontrollable fires since the 1980s.

The potential for fuel reduction to reduce wildfire intensity in a warming California

So, what’s the solution? One key approach is to bring conditions back to something closer to where they were in the 19th century by intentionally setting fire to the landscape under favorable conditions and also removing fuel mechanically. This results in less fuel to burn when wildfires occur, making them less severe and easier to contain.

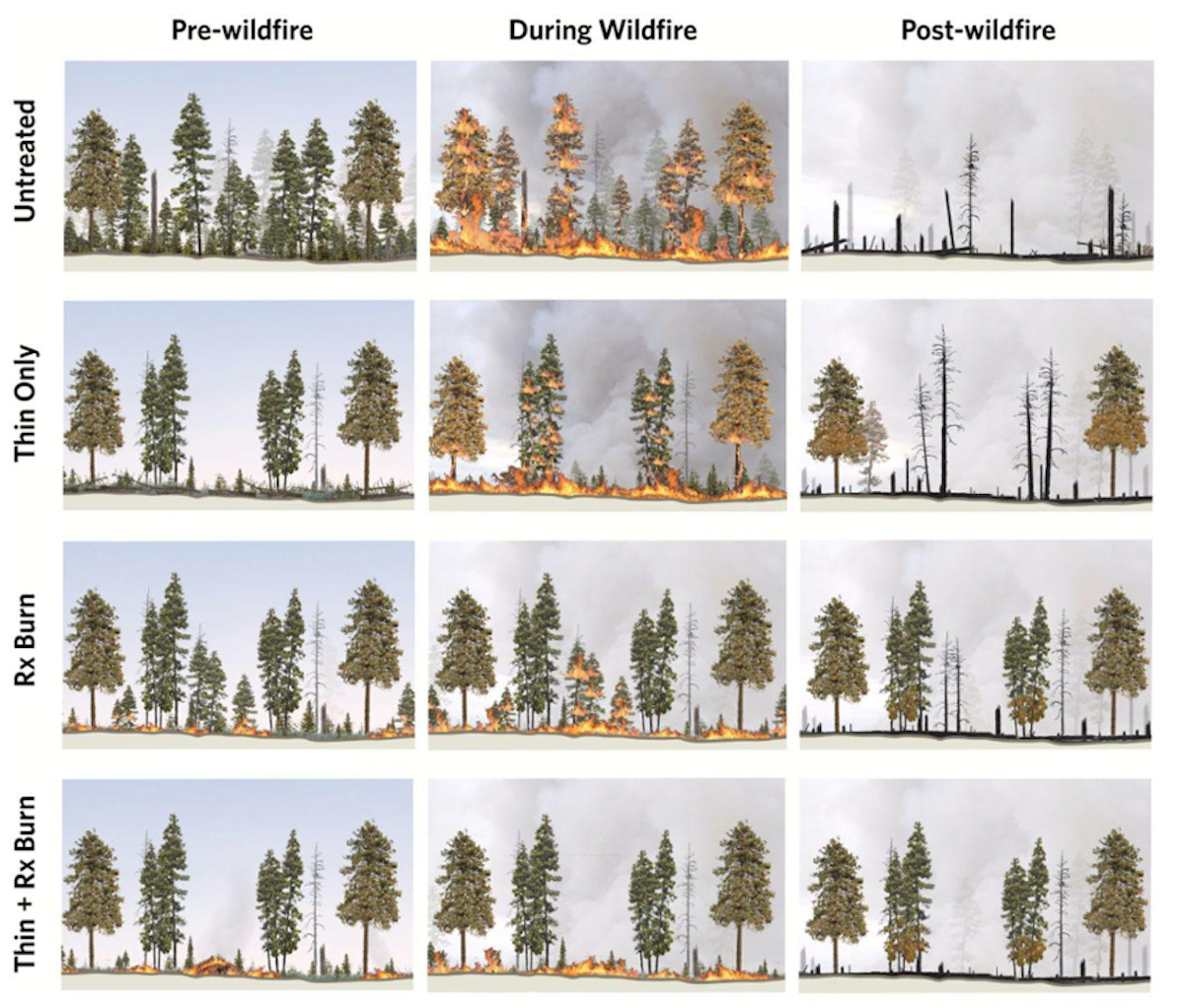

Decades of on-the-ground firefighting experience show that if a forest is overstocked and untreated, a fire can easily escalate, but thinning and prescribed burning can limit fire intensity and ultimately help protect the forest and adjacent communities.

The above diagram represents the idealized theory for how this works, but there is also ample empirical evidence that it works. This is exemplified by meta-analyses of dozens of studies, but a picture says 1,000 words. Below is a photo of the after-effects of the Bootleg Fire in Oregon, which happened to traverse an area that had no fuel reduction, an area that had recently undergone only mechanical thinning, and an area that had recently undergone both mechanical thinning and prescribed burning.

We can see that the fire was most severe in the area with no treatment; it was less severe where there was only mechanical thinning, but the forest survived relatively unscathed where both thinning and prescribed fire had recently been implemented.

So we know these practices work, and we know their general direction of effectiveness, but our recent research focused on just how well they work, specifically in terms of offsetting the impact of climate warming over the remainder of the century.

Methods of our study

The starting point for our research was over 27,000 satellite observations of fire intensity within California state lines spanning the period 2012–2020, and our goal was to understand the relative influence of both fuel and temperature on these observations.

There were three fundamental steps:

- Learn the relationships between environmental conditions (including both fuel and climate conditions) and wildfire intensity

- Extrapolate those relationships in space

- Make future projections under different warming and fuel reduction scenarios

First, we learn the relationships between observations of wildfire intensity and sixteen different environmental conditions. Many traditional regression methods assume that the influence of any predictor variable is independent of the influence of the other predictor variables and that their influence is monotonic, if not linear. However, it is well known that the influence of any one of these predictor variables will be highly conditional on the state of other predictor variables. Thus, rather than use traditional regression methods, we use machine learning models, specifically neural networks and random forests, in order to estimate the associations between the environmental conditions (or predictors) and wildfire intensity.

We confirm that these predictors do constrain wildfire intensity by testing the models on data that was held out of the training procedure.

After training the machine learning models, we extrapolate in space. Given a set of environmental conditions, the models predict what wildfire intensity would look like if a fire were to occur there at that time. Because we consistently have environmental data, we can produce maps of predicted wildfire intensity or “fire intensity potential” (FIP) maps. Below is an example from the afternoon of September 8, 2020, when large wildfires were erupting across California. This map shows where the model predicts the highest risk during that snapshot in time.

To create future projections, we placed the historical weather snapshot maps like the one above in different combinations of background warming and fuel reduction conditions to assess how changing the fuel and climate predictors might influence future statewide fire intensity potential. The background warming scenarios correspond to climate-model calculated warming from two greenhouse gas emissions scenarios—a slow emissions reductions scenario (SSP2-4.5) and fast emissions reductions scenario more in line with the Paris Agreement (SSP1-2.6).

When no fuel reduction is implemented (the top red and orange lines) we see that fire intensity potential goes up over the remainder of the century as conditions grow warmer and drier. However, the difference between the emissions scenarios isn’t very large. By mid-century, under the slower emissions reduction scenario, fire intensity potential would be about 14% higher than today, whereas faster emissions reductions would lower that increase to about 12% higher than today. By the end of the century, the gap grows a bit more, to around +25% versus +16% relative to today.

But if we scale up fuel reduction, as represented by the purple and green lines, that creates a much bigger effect. Conducting fuel reduction on 1.6 million acres per year (with a 5-year return interval), which represents 3% of the total domain, would cause a 12% reduction in fire intensity potential in 2050 relative to today and would still cause a reduction in fire intensity potential at the end of the century even under slow global greenhouse gas emissions reductions. Given that 1 million acres per year is the stated near-term goal in California, 1.6 million acres per year is within the range of plausibility. This is good news, and it is information that could be used to support these goals and facilitate their implementation in the face of multiple challenges, including funding constraints, workforce shortages, and bureaucratic and regulatory obstacles associated with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

Does this kind of research get enough attention?

This information, however, cannot be used to support these goals if it is not noticed.

This work represents the most recent iteration of research that I first published in Nature in September 2023. After publishing that paper, I wrote an op-ed critiquing that study and articulating my broader concerns about how high-profile, attention-grabbing climate science often focuses too narrowly on the most dramatic negative impacts of climate change (more here and here) at the expense of more actionable science on adaptation.

My core thesis was that customizing the research for a high-impact journal made it less useful than it would have been otherwise. Specifically, I pointed out that it was in my self-interest as a researcher to focus narrowly on the impact of climate change on a particular processed metric without considering other relevant dynamics that could offset the impact of climate change.

In much of the pushback that I got, I heard that I was wrong on this account and that, had my projections included more driving factors than just climate warming, it would have been even more attractive to a high-impact journal like Nature, not less.

The present paper represents a test of this hypothesis.

You’ll notice that the present paper was not, in fact, published in a high-profile venue, but this was not due to a lack of trying. The paper was rejected by Nature, as well as the other high-impact journals of Science, PNAS, Science Advances, and PNAS Nexus. Only once did it go to peer review in this series of submissions, and the rest were ‘desk rejected,’ meaning the editor subjectively decided that the paper was not worthy of their high-profile venue.

Is the reason that the present version landed in a lower-profile journal because it is somehow less adequate on technical grounds? No. In fact, this version of the research represents an improvement along at least seventeen dimensions, including more data, higher quality data, higher resolutions in space and time, and more sophisticated and elegant methods. The table below summarizes the improvements between the previous Nature paper (Brown et al. 2023) and the present Environmental Research Letters study.

So why was this version of the research more challenging to publish in a high-profile venue? I think the key difference lies in the framing. In accordance with what I argued in my piece in the Free Press (and elaborated on in the Chronicle of Higher Education), the path of least resistance to publishing high-impact climate science papers involves framing the research in a way that at least directionally supports global climate policies like the Paris Agreement:

“…the biases of the editors (and the reviewers they call upon to evaluate submissions) exert a major influence on the collective output of entire fields. They select what gets published from a large pool of entries, and in doing so, they also shape how research is conducted more broadly. Savvy researchers tailor their studies to maximize the likelihood that their work is accepted. I know this because I am one of them.

Here’s how it works.

The first thing the astute climate researcher knows is that his or her work should support the mainstream narrative—namely, that the effects of climate change are both pervasive and catastrophic and that the primary way to deal with them is not by employing practical adaptation measures like … better forest management or undergrounding power lines—but through policies like the Inflation Reduction Act, aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

So in my recent Nature paper, … I focused narrowly on the influence of climate change on extreme wildfire behavior. Make no mistake: that influence is very real. But there are also other factors that can be just as or more important, such as poor forest management”

The previous Nature paper (which focused narrowly on the negative impact of warming on fires) received considerable attention (even prior to my essay critiquing it) as it was covered by over 100 news outlets, including NPR, The LA Times, The San Francisco Chronicle, Yahoo News, the Japan Times, and The Times of India. This was mainly because of the built-in infrastructure that Nature has in place to widely and effectively disseminate the research they publish. Environmental Research Letters, the venue of the present paper, has no such infrastructure, and thus, the result has been that the present version of this work has been covered by a grand total of zero news outlets (as of February 2025).

So, the subsequent exclusion of the present paper from the high-impact literature is evidence in favor of my thesis that editors and reviewers mold the output of the high-impact literature to emphasize the influence of climate change over other (oftentimes more important) factors.

Which venue a paper is published in does not necessarily make a huge difference to the handful of other researchers within a sub-discipline (because they will tend to find it regardless), but it makes a huge difference for the amount of attention research receives by the public and, thus, how much the information becomes incorporated into the conventional wisdom of decision-makers.

The overall result of these dynamics is that the public and decision-makers receive the message that the main way to solve climate-related problems is through greenhouse gas emissions reductions rather than more direct on-the-ground adaptation strategies.

This is unfortunate because adaptation measures often have much higher leverage on improving outcomes, but they will be easiest to implement when they are appreciated as being effective.