Where Did the Jobs Go?

What Obama and Romney Can Learn from the Recession

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

US unemployment rates remain high and a major issue in the US presidential campaign. This post seeks to explain with simple math where the jobs went as a first step in understanding how unemployment might be reduced. The math is simple, and it helps to show how most debate over economy and employment miss what actually matters most – and that is innovation policy.

In December, 2007 the US economy employed about 138 million people. In February, 2012 that number had shrunk to about 133 million (data). Where did those jobs go? Two recent studies provide some important insight to this question.

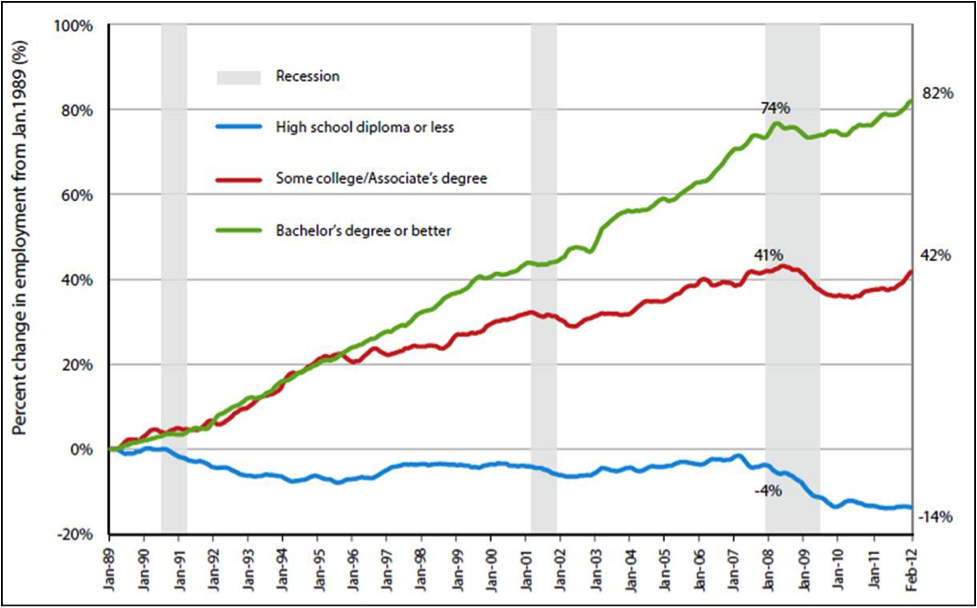

Last month, Georgetown University's Center on Education and the Workforce published a study looking at job losses from 12/2007 to 2/2012 (hence my use of those dates) by economic sector and educational attainment (here in PDF). The Figure below shows their overall results.

The graph shows that for those who attended some college, or with more post-secondary education, employment had recovered to December 2007 levels by February 2012. The balance of “lost” jobs was among those with secondary (i.e., high school) education or less.

A longer view, beyond the time frame of the recent recession, shows that all job growth in the US since 1989 has come from those with some post-secondary education, with a 14% drop in those employed with a secondary degree or less. Thus, the recent recession amplified trends that were already in place and part of the ongoing structural change in the composition of the economy.

The Georgetown report also looked at job losses by economic sector by educational attainment. This is shown in the figure below, which shows the dramatic loss of jobs by those with the least education in construction, IT, manufacturing and financial services. Together, these four sectors account for the loss of 5.6 million jobs from December 2007 to February 2012. Within those sectors 3.7 million, about two thirds, of the job losses were among those with the least education, secondary or less.

A big part of the loss of jobs of course is the nature of the recession itself, originating in the finance industry and the housing bubble – hence the large loss of jobs in construction and financial services and the bubble burst.

The loss of low-skill jobs in manufacturing and IT (and other sectors in the economy) is arguably the consequence of industries in these sectors trying to maintain productivity growth to remain competitive by shedding the lowest skilled jobs at a rate faster (slower) than the decline (subsequent rebound) in output. These numbers are borne out by looking at productivity data.

According to the BLS, in quarterly data from 2000 to 2006 labor productivity gains (in the non-farm sectors) over the previous 13 quarters (i.e., the period from Dec ’07 to Feb ’12) ranged from 10.4% to a 16.5%. During the 13 quarters examined in the Georgetown study, those rates of productivity gain over 13 quarters dipped to 5.0% to 8.9%.

Despite the recession, productivity gains were positive. These gains occurred because productivity reflects output per hour and over the period from December 2007 to February 2012, output increased by less than 1% representing the economic recovery, but hours worked decreased by almost 6%, which is why jobs have not recovered as much as the economy.

In a paper prepared for the Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium and released a few days ago (here in PDF) Edward Lazear and James Spletzer look at much of the same data as found in the Georgetown study and conclude:

The recession of 2007-09 witnessed high rates of unemployment that have been slow to recede. This has led many to conclude that structural changes have occurred in the labor market and that the economy will not return to the low rates of unemployment that prevailed in the recent past. Is this true? The question is important because central banks may be able to reduce unemployment that is cyclic in nature, but not that which is structural. An analysis of labor market data suggests that there are no structural changes that can explain movements in unemployment rates over recent years. Neither industrial nor demographic shifts nor a mismatch of skills with job vacancies is behind the increased rates of unemployment.

Lazear and Speltzer appear to get so caught up in an academic debate over “structural” versus “cyclical” changes that they focus on this debate rather than the more important questions of policies and consequences. Their inability to clearly define “structural” changes in the economy is a clear indication that any debate over “structural” vs. “cyclical” is unlikely to be resolved empirically, and thus can only provide so much insight to policy questions. Their argument appears to be that “cyclical” implies nudging by central bankers, and not much else, whereas “structural” implies other government actions. It is not difficult to see how such a framing might be easily captured in Left vs. Right politics of the day.

However, economic policy is more complicated than either/or. The recent recession showed that the long-term change in the US economy to higher-skilled employment received a one-time shock, with the economy shedding a large number of unskilled jobs. This shock was in the same direction of long-term trends in the economy with respect to low-skilled employment, especially in manufacturing. If the economic experience of the past several decades is any indication, then these jobs are not coming back, and nor should we want them to, as they are associated with low pay and low productivity.

In theory, improving productivity sounds great, but today there is the persistent matter of high unemployment in the near term, particularly among the low skilled part of the workforce. Lazear and Speltzer argue that the data suggest that,

There is no evidence that the recession resulted in a long-lasting skills gap that would require retraining experienced workers to work in different industries.

They reach this conclusion by looking at supply of workers and demand for employees, and not surprisingly, finding a pretty good balance. Over the longer term it may indeed be the case that the economy organically reverts to a lower rate of employment. The important questions for policy however are whether specific government actions can make that longer term shorter (and, of course, avoid making the longer term longer).

I think that government policy is important here, and beyond the typical debate over stimulus vs. austerity or cycles vs. structures. Because the economy is non-stationary in the sense that sectors and skills are undergoing constant change, there is always the need for training and retraining within the workforce. Because all employment growth since at least 1989 has come from those with at least some post-secondary education, this indicates that there are both supply and demand reasons to focus on retraining -- these are the people who innovate, which leads to new industries, new sectors and ultimately new jobs in a vibrant, growing economy.

Of course, the persistent unemployment will not be easily remedied simply by offering training to the millions of low-skilled workers currently unemployed. Nor will it be addressed by short-term stimulus. What is needed is a more comprehensive approach to innovation in the economy, of which constant training and retraining of workers must be a part.

The larger conclusion is that missing from much of ongoing debate over jobs is any explicit, underlying theory of economic growth, and how policies contribute to it. Academic economics has too long relied on invisible hands and academic either/ors to guide policy debate. The way that unemployment goes down is through economic growth. Both Romney and Obama appeal to economic growth, but I have no idea how either candidate thinks that they can make it happen.

Where did the jobs go? They went to a no-go zone in current debate over economics and that is a place called innovation policy.