Pathways to Progress on Climate Change, pt 3

Telling Stores about Human Security and Ingenuity

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

Frustrated by the political paralysis on climate change, in recent years, many environmentalists have focused their efforts on building a more powerful movement in support of action. Among the most notable efforts, in a 2012 cover article at Rolling Stone magazine, writer and 350.org activist Bill McKibben called for a new sense of moral outrage directed at the fossil fuel industry, a plea that helped launch the divestment movement on college campuses.

Given the urgency of climate change, “we need to view the fossil-fuel industry in a new light,” he argued. “It has become a rogue industry, reckless like no other force on Earth. It is Public Enemy Number One to the survival of our planetary civilization."

A year earlier, in a cover article at The Nation magazine, fellow 350.org activist Naomi Klein urged progressives to copy the strategies of the U.S. conservative movement: “Just as climate denialism has become a core identity issue on the right, utterly entwined with defending current systems of power and wealth, the scientific reality of climate change must, for progressives, occupy a central place in a coherent narrative about the perils of unrestrained greed and the need for real alternatives.”

Though in the short term, these calls to action from voices admired by progressives might bring much needed pressure to bear on targeted decision-makers and elected officials, in the long term such strategies if not also balanced by alternative investments in civic engagement by the expert community may only intensify polarization and gridlock.

Consider that among the key findings of social scientists studying public perceptions of climate change is that the most knowledgeable and cognitively sophisticated partisans tend to be the most divided in their views of climate change.

A major reason, they argue, is that in comparison to their less informed counterparts, these individuals are better attuned to what other members of their cultural group think and believe. It is the desire to remain aligned with the outlook of others in their cultural group that strongly shapes their opinion on climate change.

Therefore, when the most prominent voices calling for action on climate change are perceived by the broader public to be strongly if not exclusively liberal in their outlook, the risk is that many Americans are likely to dismiss climate change as a threat and to view policy actions to address the problem as in conflict with their own group identity.

As I review in this essay, to counter balance the risk of deepening polarization, the expert community and their organizations will need to recruit opinion-leaders from a diversity of societal sectors; and encourage these opinion-leaders to join them in telling stories about climate change that resonate with their respective cultural reference groups.

This essay and others in the series are adapted from a forthcoming chapter that I contributed to the Routledge Handbook of the Public Communication of Science and Technology.

Telling Stories about Human Health and Security

As an example of how to develop and test more broadly engaging frames of reference about climate change, in a series of studies conducted with George Mason University’s Edward Maibach and several colleagues we investigated how a diversity of Americans react to information about climate change when the issue is framed in terms of human health and security.

In this research funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, our goal was to inform the work of public health professionals, municipal managers and planners, and other trusted civic leaders as they seek to engage their communities on climate change.

Framing climate change in terms of public health stresses climate change’s potential to increase the incidence of infectious diseases, asthma, allergies, heat stroke, and other salient health problems, especially among the most vulnerable populations: the elderly, children, and the poor. In the process, these risks make climate change personally relevant to new audiences by connecting the issue to health problems that are already familiar and perceived as important.

The frame also shifts the geographic location of impacts, replacing visuals of remote Arctic regions, animals, and peoples with more socially proximate neighbors and places across local communities and cities. Coverage at local television news outlets and specialized urban media is also generated.

As we have argued with colleagues in several recent reviews, efforts to protect, defend, and make more secure people and communities are also easily localized. Moreover, state and municipal governments have greater control, responsibility, and authority over implementing climate change adaptation-related policy actions, thereby enabling progress during a time of intense political gridlock at the national level.

In addition, recruiting Americans to protect their neighbors and defend their communities against climate impacts naturally lends itself to forms of civic participation and community volunteering.

In these cases, because of the localization of the issue and the non-political nature of participation, barriers related to polarization may be more easily overcome and a diversity of organizations can work on the issue without being labeled as “advocates,” “activists,” or “environmentalists.”

Moreover, once community members from differing political backgrounds re-focus their attention on a broadly inspiring goal like protecting their families, neighbors and local way of life, then when the time is right, the networks of trust and collaboration formed can be used to move this diverse segment toward cooperation in pursuit of national policy goals.

To test these assumptions, in an initial study, we conducted in depth interviews with 70 respondents from 29 states; recruiting subjects from 6 previously defined audience segments.

These segments ranged on a continuum from those individuals deeply alarmed by climate change to those who were deeply dismissive of the problem.

Across all six audience segments, when presented with information that framed climate change in terms of public health, individuals said that the information was both useful and compelling, particularly at the end of the essay when locally-focused mitigation and adaptation related actions were paired with specific benefits to public health (see B section of this figure).

In a follow up study, we conducted a nationally representative Web survey in which respondents from each of the 6 audience segments were randomly assigned to 3 different experimental conditions allowing us to evaluate their emotional reactions to strategically framed messages about climate change.

Though people in the various audience segments reacted differently to some of the messages, in general, framing climate change in terms of public health generated more hope and less anger than framed messages that defined climate change in terms of either national security or environmental threats.

Somewhat surprisingly, our findings also indicated that in contrast to the locally focused human health and security frame which tended to diffuse anger among the most doubtful and dismissive subjects, the more internationally focused national security frame appeared to “boomerang” among these segments, eliciting feelings of strong anger.

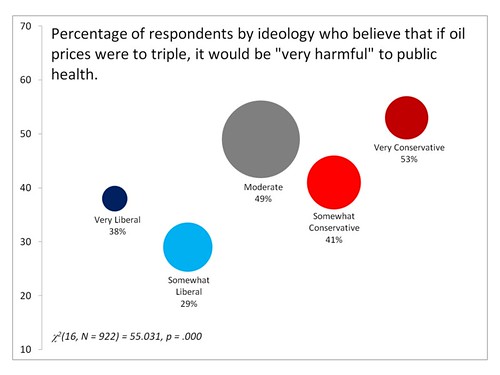

In a third study, we examined how Americans perceived the risks posed by a major spike in fossil fuel energy prices. According to our analysis of national survey data, approximately half of American adults believe that our health is at risk from major shifts in fossil fuel prices and availability, and an even greater percentage perceive strong risks to our economy.

Moreover, this belief was widely shared among people of different political ideologies and was the most strongly held among conservative individuals otherwise dismissive of climate change. (See figure below. Bubble size is proportionate to percentage of each group within U.S. adult population as measured at time of the survey).

Our findings suggest that many Americans would find relevant and useful communication efforts that emphasized energy resilience strategies that reduce demand for fossil fuels, thereby limiting greenhouse emissions while also preparing communities for energy shortages or price spikes that might result from extreme weather impacts (regardless of whether these impacts are related to climate change or not.)

Examples include improving home heating and automobile fuel efficiency, increasing the availability and affordability of public transportation, and investing in government-sponsored research on cleaner, more efficient energy technologies.

Emphasizing Human Ingenuity and Local Cooperation

For journalists and other media producers, their efforts to engage Americans on climate change would also benefit from a careful re-consideration and diversification of the stories that they tell about the problem and its possible solutions.

Drawing on Dan Kahan's "cultural cognition" research, one principle for a new type of media storytelling that could have broader appeal with Americans is to focus on the types of narratives that connect climate change to "cultural meanings of human ingenuity and of overcoming natural limits on commerce and industry that at least partially offset the threat that crediting such information would normally pose...," as Kahan and co-authors write.

In a critique of the Showtime climate series Years of Living Dangerously, Michael Shellenberger and Ted Nordhaus echo this generalizable suggestion by Kahan, arguing that the series could broaden its appeal by featuring portrayals of how:

....France scaled up nuclear energy to more rapidly reduce its carbon emissions than any other nation in history. Or how a Texas oil and gas man teamed up with the Department of Energy to release natural gas from shale, replacing coal and resulting in greater carbon emissions reduction in the US than in any other country in the world since 2007. Or perhaps there [could] be a story about Floridians working together to adapt to rising sea levels without thinking to fight over whether or not it is human-caused.

Independent of Kahan's research and this critique of the Showtime series, an organization applying research-based principles to their communication strategies on climate change is ecoAmerica (a group which I have worked with as a consultant and advisor).

As part of their MacArthur foundation-funded “Momentus” campaign, ecoAmerica is collaborating with opinion-leaders and organizations recruited from societal sectors new to the climate change debate including public health, faith communities, business, higher education, and local municipalities.

Their goal is not only to empower a more nationally representative set of cultural voices talking about why climate change matters, but also to promote a new master narrative about the issue.

This new narrative weaves together themes of national unity, pride, moral and religious identity, and community responsibility; emphasizing the risks to human health and well-being as well as the economy.

A vision for progress includes Americans coming together to defend their local communities against the impacts of climate change, regardless of what they might believe about the causes of the problem.

Combining Storytelling with Effective Policy Advice

Yet as useful as these studies and innovative storytelling examples might be, even the most effective communication strategies must also be complemented by other types of investments.

One of those investments is for experts to carefully assess the role that they and their organizations play as policy advisors and advocates, a topic explored in depth in a recent guest post by Greg Alvarez, a graduate student at American University.

As I review next week in the fourth essay in this series, instead of tacitly allowing their expertise to be used in efforts to promote a narrow set of policy approaches, experts and their institutions can boost their impact by serving as “honest brokers,” expanding the range of policy options and technological choices under consideration by elected officials and key stakeholders.

Not only will we need a diversity of ideas and approaches to manage the risks of climate change, but the broader the menu of policies and technologies that experts can help call attention to, the greater the opportunity there will be for agreement among decision-makers on paths that will move us forward on climate change.

Other Essays in the "Pathways to Progress on Climate Change" Series:

Part 1: Lessons from Research on the Politics of Technical Decisions

Part 2: Wicked Psychology and Ideological Message Machines

Part 3: Telling Stories about Human Security and Ingenuity

Part 4: Diversifying Policy Options and Promoting Public Debate

Citation: