Solar Panels Are Not Cell Phones

The Developing World Won’t Leapfrog the Traditional Grid to Solar Microgrids

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

“Developing countries can leapfrog conventional options,” the UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon wrote in the New York Times last year, “just as they leapfrogged land-line based phone technologies in favor of mobile networks.”

This seems like good news for those who envision solar panels powering the future economies of today’s developing countries. The Sierra Club believes that the “hardened and centralized infrastructure of 20th-century power grid” will be unnecessary in countries where little or no infrastructure currently exists. The White House recently announced that $1 billion in Power Africa investments (out of $7 billion for the whole initiative) will be directed at off-grid projects, writing that distributed generation “holds great promise to follow the mobile phone in leapfrogging centralized infrastructure across Africa.”

Hold the mobile phone. While solar panels have become cheaper in recent years, they are still the most expensive way to generate electricity, and still far more expensive than fossil fuels — especially in natural gas-rich regions like Africa.

Solar panels have come down in price but nothing like cell phones. Better cellular networks, fewer components, and exponential improvements in computing power have given rise to ultra-cheap mobile phones. Solar panels declined from $77 per watt in the late 1970s to less than $1 per watt today. That sounds impressive until you consider that the cost of computer chips — which are used for the circuit board of the phone — are today one one-millionth the cost (per unit power) in the late 1970s.

Cheap cell phones have helped economies grow by reducing transaction costs and making markets more productive. By contrast, solar panels are a more expensive and less reliable form of electricity. One of the most popular mobile phones in Africa — the Samsung E250 — retails for about $100. An E250 can help workers communicate with their families, check the prices of goods and services in faraway villages, and access the Internet. A $100 solar panel can power one or two light bulbs for a few hours a day.

A recent report by the Center for Global Development finds that 60 million more Africans would gain electricity if the same $10 billion were invested in natural gas and not just renewables like solar. This is both because solar is expensive and because Africa is awash in natural gas. In fact, Africa has more natural gas than North America. The difference being, of course, that where we consume about 8 percent of our proven gas reserves annually, Africans only consume 0.8 percent of theirs.

Solar-powered micro-grids can provide very basic energy access, and they are gaining traction, especially where they replace costly diesel generators in remote regions. But they remain expensive, provide extremely low levels of electricity, and depend on back-up generators to keep the lights on when the sun isn’t shining. (The new IPCC report acknowledges the challenge of integrating intermittent renewable energy into energy systems.)

While the information transmitted via cell phone – whether coordinating a business transaction or communicating with faraway family members – can carry important economic and social consequences, the energy required to do so is tiny. By contrast, the amount of energy needed for building and powering irrigation systems, factories, and cities, is very large.

A modern civilization simply cannot be built on distributed solar power, but then, off-grid enthusiasts have never been much for civilization. The idea that small-scale, low-energy, decentralized technologies like solar can and should power poor countries dates back to the “appropriate technology movement” of the late 1960s and early 1970s, inspired by E. F. Schumacher’s vision of “small is beautiful.”

Such a romantic vision might have been understandable in 1972, when China was still a peasant society that few imagined could become a superpower. But today China and other developing nations are rapidly approaching Western energy consumption levels, and African nations are starting to benefit from widespread urbanization and electrification. In the 2000s, sub-Saharan Africa’s urban population grew by 100 million, and the number of people getting new electricity access in cities was twice the number of people getting new access in the countryside.

Data: World Bank, International Energy Agency, and the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA)

While the patronizing language of appropriate technology is gone, the United Nations carries on with the low-energy vision for Africa. Consider the United Nations’ flagship energy access program, “Sustainable Energy for All,” which defines yearly “energy access” for the poor at levels that are barely enough to power a fan, a couple of light bulbs, and a radio for five hours a day.

To the UN, a year’s worth of “energy access” in the developing world is equal to what the average European consumes in less than a month and a typical American consumes in a little over a week. That’s not enough to satisfy basic consumption needs; much less to build a modern infrastructure.

Source: Mark Caine et al., “Our High-Energy Planet,” Breakthrough Institute and Consortium for Science, Policy and Outcomes, 2014.

A new report by a group of international energy and development experts calls on the United Nations and other international agencies to plan for far higher energy consumption in sub-Saharan Africa and in other regions that rely on burning wood and dung for energy. Africans want more than a couple of light bulbs a day, the report’s authors argue. They want the same civilization we enjoy: roads, pipes, water purification plants, hospitals, and schools. Creating those things requires always-on, baseload, reliable electricity that is, above all else, cheap. Just as mosquito nets are no replacement for hospitals, solar lanterns are no replacement for modern electricity grids.

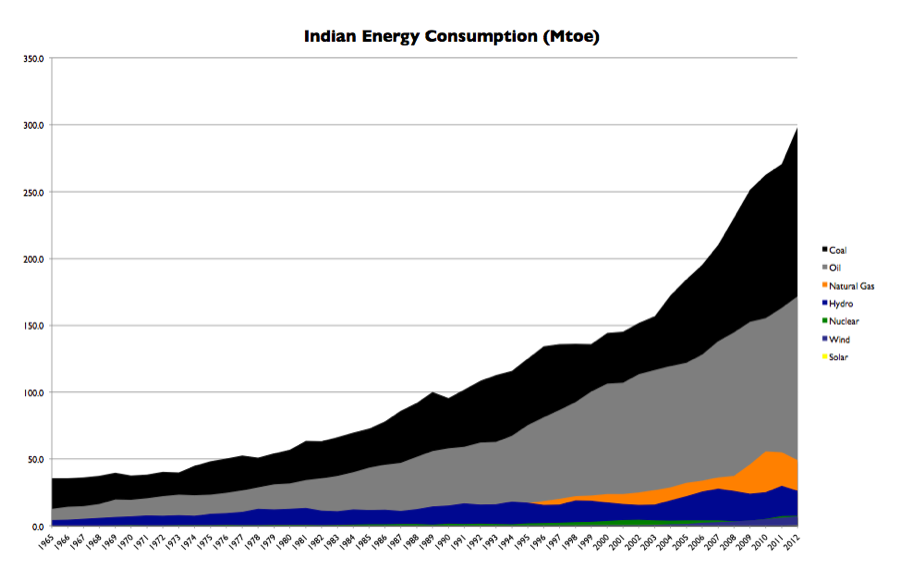

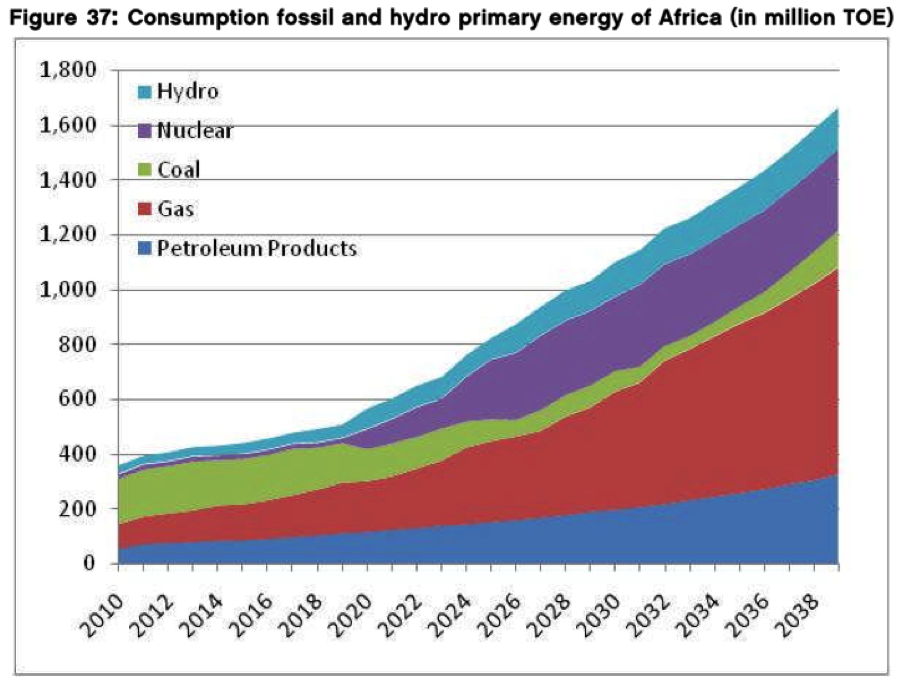

It’s no surprise, then, that experts expect China and India to continue to expand their base of coal-fired power in the coming decades. Africa, meanwhile, is projected to power its rapidly urbanizing population with abundant natural gas and hydroelectric energy, much more so than with solar or wind. For renewables to rival grid-based gas and hydro in the coming decades, major innovation in generation and storage will be required.

Data: BP Statistical Energy Review 2013

Source: Study on Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA), “Africa Energy Outlook 2040,” The New Partnership for Africa’s Development, African Union, and Africa Development Bank, 2011.

In the end, information is not electricity, and comparing them is inappropriate and deliberately misleading. While the IPCC’s finding that wind and solar are getting better and cheaper means that these technologies will grow at the periphery of established energy systems in many regions, it does not mean that they will replace centralized grids in developing countries that currently lack basic energy infrastructure.

Alex Trembath is a research analyst and Max Luke was formerly a policy associate at the Breakthrough Institute.