Giving the Lie to The Great Meat Displacement Theory

Two new studies myth-bust both extremities of the meat debate

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

In May, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed into law a bill that bans the production and sale of cultivated meat—also known as cell-cultured, or lab-grown meat—in his state. It apparently didn’t matter that no cultivated meat was being produced in Florida, nor had any ever been sold there.. Quickly thereafter, Alabama Governor Kay Ivey signed a similar bill into law. As in Florida, no cultivated meat production nor sales had ever occurred in Alabama.

The bans are not limited to the United States. In November 2023, Italian lawmakers outlawed cultivated meat to, in the words of the Italian minister of agriculture, keep Italy “safe from the social and economic risks of synthetic food.” Italy isn’t the only European country scared of futuristic “meat.” Representatives of the French and Austrian governments have also expressed concern over the social and economic impacts of cultivated meat on traditional farming.

These concerns are off base. For now, companies have been able to make small batches of cultivated meat products, but at nowhere near the scale or price-point that could come close to disrupting the conventional meat industry. Plant-based meat, which is already in supermarkets, restaurants, and kitchens around the world, has likewise come nowhere close to significantly displacing conventional livestock and poultry products.

Why, then, are all these politicians on the warpath against alternative proteins?

In part, because of marketing gaffes from some of the biggest names in alternative proteins. Patrick Brown, the founder of Impossible Foods, has publicly stated that his goal is to “get rid of the friggin cows.” In a 2019 New Yorker profile, Brown predicted that, by 2024, Impossible would have already set the death of the beef industry in motion and would be on its way to bankrupting the pork and poultry industries as well.

Brown’s inflammatory prophecy—which later proved wrong—incited quick opposition. Left-leaning foodie activists like Mark Bittman found the Silicon Valley brashness of Brown and the rest of the alternative protein industry distasteful. Conventional meat producers found the claims ridiculous. Rightwing politicians latched onto threats to kill meat as an opportunity to win a culture battle against climate-focused democrats and coastal elites.

The naturalistic fallacy is prevalent across the wide spectrum of alternative protein opposition, as well. Senator John Fetterman, a democrat from Pennsylvania, tacitly supported the Florida ban, mainly citing the “unnatural” quality of the product. In Europe, where the slow food and anti-globalization movements have found homes on both the left and right, opposition to cultivated meat is as much about protecting farmers as the “natural” and culturally appropriate forms of consumption. For many on the right, as well, conceptions of masculinity revolve around eating meat and other animal products, making alternative proteins a threat to their own sense of manhood.

While these cultural oppositions to meat alternatives are unlikely to be solved through new analyses, two new economics studies (not yet peer reviewed) allow a more empirical look at what these novel alternatives mean for livestock producers.

The first, by Michigan State’s Vincenzina Caputo, Oklahoma State’s Jayson Lusk, and BTI’s Dan Blaustein-Rejto, uses an economic experiment to estimate the potential of plant-based meats to replace conventional meats and other products at varying prices. The paper also looks into how plant-based meat prices will influence livestock and poultry production in the United States.

The second paper, by University Torcuata di Tella’s Nicolas Merener, Blaustein-Rejto, and myself, evaluates the potential impact of plant-based meat adoption on global crop prices, and what those prices might mean for crop producers.

Although focused on separate issues, these papers tell a clear story: alternative meats, even if they do meet the alternative protein industry’s projected short-term goals, will not meaningfully hurt the bottom line of conventional livestock and crop producers.

Consumer Choice and Livestock Replacement

The concern that alternative proteins will kill the meat industry relies on the assumption that, if successful, alternative proteins can serve as a substitute for a significant portion of meat consumption. To date, alternative protein has not come close. Plant-based meat sales dipped in 2023, falling from $8.2 billion to $8.1 billion. And the sale of cultivated meat remains infinitesimal. By contrast, conventional meat sales in the United States increased by 0.7% to $122 billion in 2023.

Analysts and proponents of the alternative protein industry argue that, as alternative protein prices go down, consumers are bound to purchase more plant-based products and less conventional meat. Although this may be true in the long-run, substantial short-term substitution of beef, chicken, and pork with plant-based alternatives will not come from declining plant-based meat prices alone.

For example, Caputo, Lusk, and Blaustein-Rejto surveyed more than 1,000 respondents to assess whether plant-based meat products acted as substitutes for conventional meat. They broke their survey into two categories, food consumed at home (i.e. groceries) and food consumed away from home (restaurants, fast food, etc.).

For groceries, the authors found, plant-based meats are complements for conventional meats.

When prices of plant-based meats were lowered in the experiment, consumers generally purchased more of both plant-based and conventional meat. This is counterintuitive, but aligns with other recent studies of supermarket scanner data. This could be the case for a few reasons: consumers might be purchasing both plant-based and conventional products to compare them; when prices for plant-based meat are low, consumers can purchase more of it, and still afford to buy some conventional meat in addition; or, consumers purchase both plant-based and conventional meat simultaneously to satisfy the preferences of everyone they’re serving at home. All-in-all, that plant-based meats and conventional meats are complementary for grocery shoppers is surprising.

At restaurants, the authors discovered, consumers are far more price-sensitive about their choices compared with shopping for groceries, meaning that changes in price have a bigger effect on what consumers choose.

The differences do not end there. In contrast with grocery consumption, plant-based and conventional meat products do substitute for (rather than complement) each other when consumers eat away from home. As prices go up for conventional products at restaurants, plant-based food consumption increases, and vice-versa. Still, consumers were far more likely to choose a conventional meat product over a plant-based alternative.

Caputo, Lusk, and Blaustein-Rejto use their findings to assess what a 5% decrease in the price of various plant-based meat products, tofu, and salmon would mean for the farm level production of chicken and beef. For groceries, the authors find that a 5% decrease in plant-based beef would actually increase the total quantity of conventional beef and chicken “parts” produced (although by less than 0.1%) and would lead to a 0.01% decrease in chicken breast. Across the board, a 5% reduction in the price of meat alternatives resulted in a small increase in the amount of cattle and chicken produced at the farm-level (See Table).

For restaurant and other food away from home, the authors saw larger impacts on conventional meat from a decrease in prices of plant-based products, but the overall scale remained insignificant. The study projects that a 5% reduction in the price of plant-based beef products at restaurants would reduce sales of ground and non-ground beef by 0.09% and 0.11%, respectively, leading to a minimal (0.06%) decrease in farm-level cattle numbers. A 5% reduction in plant-based chicken nuggets had even less impact, with a 0.04% reduction in ground-beef production and a 0.06% reduction in chicken “parts.”

In contrast with the impact of grocery prices, a 5% reduction in meat alternative prices at restaurants resulted in a slight decrease in total farm-level production of cattle and chicken. But, the impact remained relatively insignificant. The reduction for plant-based beef resulted in a 0.06% reduction in total cattle produced, and a 0.01 decline in chicken produced at the farm level. Reductions in plant-based chicken prices saw an even smaller effect—farm-level cattle numbers would decline by 0.001% and farm-level chicken by 0.01%.

The authors conclude that “our findings from the economic model indicate that lowering prices of plant-based beef and chicken alternatives is unlikely to significantly impact conventional poultry and livestock production.”

Conventional meat producers have little to fear when it comes to the displacement of their products by plant-based meats. Caputo, Lusk, and Blaustein-Rejto’s findings even give more reason for why large meat companies should develop their own plant-based product lines as both an alternate revenue stream, and an opportunity to take advantage of complementary consumption.

Alternative Proteins and Global Grain Markets

Caputo, Lusk, and Blaustein-Rejto show that falling prices for plant-based meats will not likely trigger a significant displacement of conventional meat. That does not mean displacement is impossible, or even unlikely. But rather, if it happens, it will likely take time, improvement in product qualities like taste, appearance, texture, and changes in broader culture and consumer preferences. Alternative proteins will need something to get opponents over the “ick” factor other than price changes.

If plant-based meats do find their way into customers’ shopping baskets and force some small displacement of conventional meat, the impact may be greater for the producers of feed inputs for meat rather than the meat producers themselves. The paper by Merener, Blaustein-Rejto, and myself finds that the small amount of displacement that is plausible in the short term will likely impact crop prices for common feed crops like corn and soybeans.

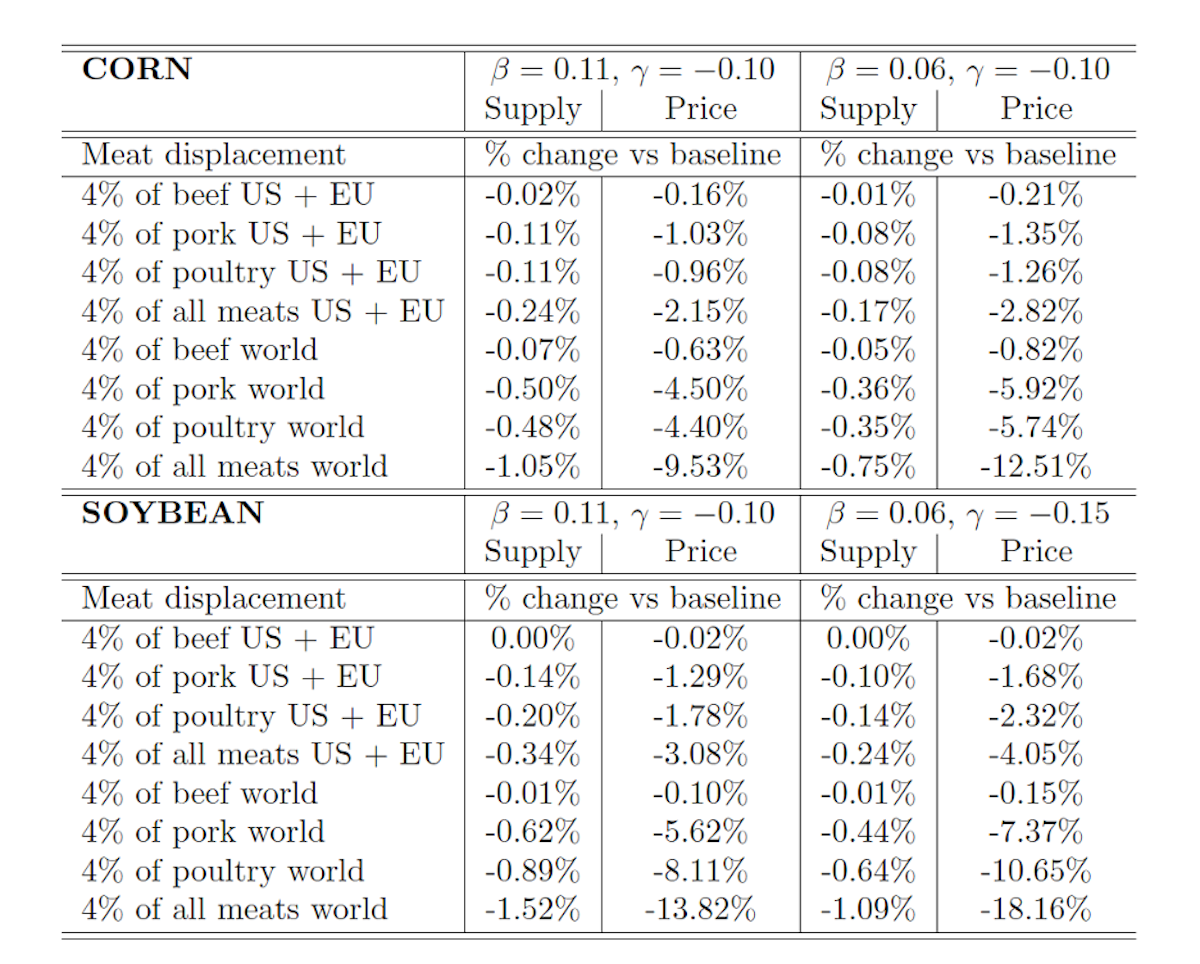

If by 2031, for example, plant-based meats induced a 4% decrease in conventional meat production on a global scale (as compared to 2031 projections for meat production), prices would decline by as much as 12.51% and 18.16% for corn and soybeans, respectively, Merener, Blaustein-Rejto, and I found in our paper. Those price declines could harm the farm sector in countries with high corn and soy production like Argentina, Brazil, Ukraine, and the United States, with varying degrees of severity. Smaller exporting countries would see little impact. Price declines for corn and soybeans would, invariably, occur alongside price increases for inputs to plant-based products—including peas and legumes—although it’s unclear to what degree the additional income could offset the lost income due to lower corn and soy prices.

One positive side-effect of this would be lower food costs for developing countries that rely on staple crops for a larger portion of their food supply. Because the impacts would mostly be felt by the largest exporters of crops, net importers could benefit from the price shifts and potentially improve food security.

When estimating the result of more local substitution of plant-based products for conventional meat, the impact is far less significant, even when accounting for a range of elasticities of demand and supply. If 4% of U.S. and EU beef consumption was replaced by plant-based meats, for example, corn and soybean prices would decline by 0.21% for corn and 0.02% for soybeans at the most. A substitution effect for pork would induce a 1.35% price decrease for corn and 1.68% decrease for soybeans, and the effect for chicken substitution would be 1.26% and 2.32%. Plant-based substitution of beef has a much smaller impact on crop prices than pork or chicken mainly because a smaller portion of cattle feed comes from staple crops.

While these impacts on prices are not completely insignificant, they are much smaller than crop price impacts from other factors. The COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian Invasion of Ukraine sent crop prices skyrocketing due to threats to exports of both Russian and Ukrainian grains. In turn, from spring of 2020 to spring of 2022, corn prices more than doubled. So did soybean prices. Annual variation in crop prices can be large, and have many factors. Any crop price impact that plant-based meats will have in the future might be totally overwhelmed by other, larger influences.

Overall, the displacement of conventional meat with plant-based products would have some effect on global agricultural production and markets, but the precise effect would depend on the extent of displacement, where it occurs, and what kind of meat is being displaced.

The Great Displacement Theory

The two papers clearly show that fears of conventional livestock’s displacement caused by plant-based meat are overstated. That would be equally true for cultivated meat, which is significantly more expensive than both plant-based and conventional products, at an earlier stage of technological and commercial development, and is generally unavailable to the public to try, let alone purchase.

A more thoughtful approach, from both the critics and the proponents of alternative meat would be realistic about potential impacts, both on producers and consumers. It would drop the “winner-takes-all” mentality—as most rational observers already have—and focus on improving the livelihoods of all involved.

Ironically, “big meat” seems to have already gotten this memo. Brazilian giant JBS has its own plant-based protein product lines and, in 2023, invested in a cultivated-meat research facility in Brazil. Tyson Foods, another giant meat company, also sells plant-based meat and has invested in the cultivated meat firm, Upside Foods (previously known as Memphis Meats), and plant-based meat firm Beyond Meat, prior to their IPO. For these firms, the success of alternative meats would also mean the success of the meat industry.

After all, growth in alternative proteins must be understood in the context of a quickly growing global market for meat, of all kinds. The OECD and FAO project that between 2021 and 2031, global meat consumption will increase by 14%. So, if anything, displacement of conventional meat by alternative proteins will simply slow the growth in livestock and poultry production, not shrink animal agriculture.

There are plenty of things for politicians to do to support agricultural producers. It’s abundantly clear that banning cultivated meat or attacking plant-based products is not one of those things.

It’s also abundantly clear that alternative proteins won’t save the world, at least not by themselves.

Yes, alternative proteins have environmental benefits, even if they simply limit the growth in demand for conventional livestock—especially beef. But as long as they are not on track to significantly displace conventional meat, they will not be a meaningful strategy to reduce the carbon footprint of agriculture.

Rather, improving livestock production efficiency, adopting methane reduction technologies for beef production and manure management, and working on piece-meal strategies to decarbonize livestock production must also be taken seriously as ways to reduce the greenhouse gas impact of agriculture.

None of this will radically change the face of agriculture. Ranchers will ranch. Farmers will farm. That’s an unappealing future for the many advocates and activists who wish to see factory farms shuttered, society veganized, and farm animals set free. It’s an equally unfortunate future for the politicians and pundits who need to create chaos to win the culture war.

But at the end of the day, it’s a future where abundant meat—whether conventionally produced, made in a factory, or produced from plants—can feed a cleaner world.