Cutting Beef Isn’t the Only Way

Productivity Gains Can Significantly Reduce Global Emissions

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

When it comes to agriculture’s carbon footprint, cattle are the metaphorical elephants in the room. Beef and meat from other ruminants—like goats and sheep—have a larger carbon footprint per pound, calorie, and gram of protein than most other foods. This is largely because ruminants emit methane during digestion and because forests are often cleared for grazing. Beef production alone accounts for about 5% of global greenhouse gas emissions according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Some estimates put that figure higher when deforestation and other land-use changes are fully accounted for. With demand rising, production of beef and other ruminant meat is expected to further warm the climate by at least 0.14–0.31°C (0.25–0.56° F) by 2100, highlighting the need for fast and effective mitigation.

Although cutting beef consumption in high-income countries is frequently proposed as necessary to reduce agriculture’s emissions, another strategy offers particularly large mitigation potential: improving the productivity of beef production systems worldwide. In many regions, especially where beef demand is growing, boosting yields and efficiency—through better feed, breeding, and management practices—can significantly cut emissions and free up land for reforestation or other restoration.

In fact, increases in productivity that are as ambitious as the dietary shifts often proposed could cut emissions from beef by more than one-quarter. Given the substantial environmental benefits, in addition to the well-known food security and nutritional benefits, dramatically improving beef productivity should be a priority for international development, food security, and climate groups alike.

Improving Productivity Reduces Emissions

Simply maintaining recent rates of productivity growth has tremendous potential to reduce emissions. Between 2000 and 2018, global methane emissions per unit of livestock protein decreased due to productivity gains that were driven by better feed and management. One study estimated that continuing this trend through 2050 would limit growth in livestock methane emissions to 15%–21%, compared to 51%–54% without productivity growth. This applies not only to methane, but also other greenhouse gases. FAO estimates that if livestock productivity continues improving at its recent pace, total livestock greenhouse gas emissions in 2050—including methane, carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide—would be 24% lower than they otherwise would be.

However, there is little reason to settle for past rates of growth. With stronger international support and investment, beef production could become far more efficient and reduce emissions more dramatically.

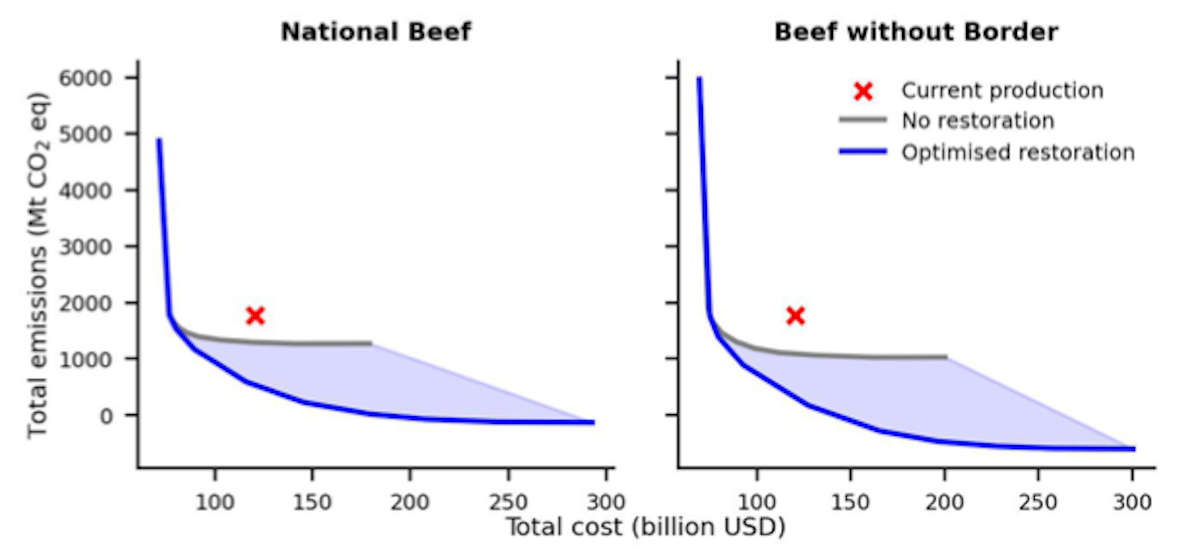

New research shows the extent to which beef production emissions could be reduced by optimizing cattle feed and shifting the location of production either within national borders or beyond borders to the most efficient countries. At the most ambitious level, optimizing feed and relocating beef production to countries with the lowest emissions per lb of beef produced, such as the US, could reduce emissions by 83% (about 1.5 billion metric tons CO₂e per year) if combined with restoration of land that is freed up, all while maintaining today’s production levels and costs (Figure below, right panel).

Under a more realistic scenario that keeps the amount of beef production constant within countries (Figure below, left panel), shifting feed composition and production within countries could reduce emissions by 27% with no additional cost. Restoration of previously used land could offset a large portion of remaining emissions, cutting total emissions to 70% below current levels. Further shifts in production and restoration that increase costs could cut emissions further, potentially offsetting them entirely in the near-term under either scenario.

More limited productivity growth could still significantly reduce emissions. We estimate that closing half the gap in emissions intensity between each country and the lowest-emitting country with a similar climate could yield a 16% global cut in beef emissions. For example, Colombia would need to close half of the gap between their current beef emissions intensity and that of beef produced in Ecuador, Mongolia half of the gap to Uzbekistan. Since many countries with similar climates are also economically and politically similar, such productivity gains could often be achieved through adopting existing practices or technologies and are unlikely to require radical shifts in production. Moreover, these estimates do not account for avoiding land-use change or restoring land made available by higher productivity, which would increase total mitigation.

Through the same methodology, we estimate that the global emissions from pork production could be reduced 16%, while the emissions from global production of chicken meat could fall an impressive 30%. The net effect of this would be a reduction in annual on-farm emissions of 24 million metric tons for pork and 19 million metric tons for chicken. The net effect of a 16%reduction in global beef emissions is an order of magnitude greater 348 million metric tons of CO2e per year.

Key Strategies for Boosting Beef Productivity

Several evidence-based strategies can significantly increase cattle productivity, lowering emissions per pound of beef:

1. Improving Cattle Nutrition: Enhancing cattle diets by providing higher-protein or more digestible feeds can help cattle gain weight faster and produce more meat per unit of feed. This shortens the time to market weight and also cuts methane emissions per pound of beef.

2. Selective Breeding: Breeding cattle for traits like better feed efficiency or improved fertility can reduce emissions. Selective breeding for animals that perform well on lower-quality pastures can also help avoid expanding grazing land into forests or other ecosystems.

3. Pasture Management: Good pasture management— as detailed in our report on Achieving Peak Pasture—can increase forage quality and boost yields, reducing land use per pound of beef. While this has the potential to also increase carbon sequestration, the higher productivity itself curbs emissions by lowering the need for more land.

4. Adopting New Technologies: Innovations like methane-reducing feed additives show great promise. Some additives, such as those derived from seaweed, have reduced methane emissions by up to 80% or more in some studies. They could potentially also increase feed efficiency. About six percent of beef cattle energy intake is typically lost as methane. Feed additives or other interventions that enable cattle to convert this lost energy to body weight instead could boost productivity.

How Ambitious is it to Shift Global Diets?

Although improving beef productivity is a clear path to reducing emissions, many policymakers and climate advocates continue to focus on curbing demand for beef. An influential study in Science estimated that gradually shifting toward plant-based diets from 2020 to 2050 could cut food-related emissions by nearly half, and the World Resources Institute (WRI) has similarly projected large emissions savings from substituting legumes, chicken, or pork for beef.

Though there is broad agreement that reducing meat and dairy consumption would be effective at reducing emissions, the proposed dietary shifts often require unprecedented changes that are as ambitious as the shifts in production detailed above. WRI’s modeling found that a 30% reduction in global ruminant meat consumption could halve agriculture’s emissions in 2050. But achieving that drop would be “highly ambitious” and might demand “breakthrough technologies” such as lower-cost cultured meat. U.S. consumption of beef and other ruminant meat, for instance, would have to fall 43% below 2010 levels by 2050—eight times faster than the decline from 2010 to 2021. Such rapid, widespread changes in consumer behavior are relatively rare, and where they have occurred in the past such as in Uruguay, they were often driven by economic crises or other major disruptions.

Takeaway Message

Reducing beef consumption in high-income countries can certainly help cut emissions, but improving beef production offers an equally—and often more—effective path for regions expecting demand growth. Policies that support producing beef where it’s most efficient, restoring land, and adopting productivity-enhancing practices and technologies can meaningfully shrink the carbon footprint of beef without requiring unprecedented changes in consumer behavior.

In the global effort to limit climate change, beef must be viewed as part of the solution rather than just as a problem. With strategic investments in productivity, beef producers can better meet rising global demand while contributing meaningfully to emissions reduction goals. Ultimately, improving productivity should be prioritized alongside—and, in many cases, ahead of—dietary shifts.