Is Pot Growing Green?

Assessing the Carbon Footprint of Cannabis

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

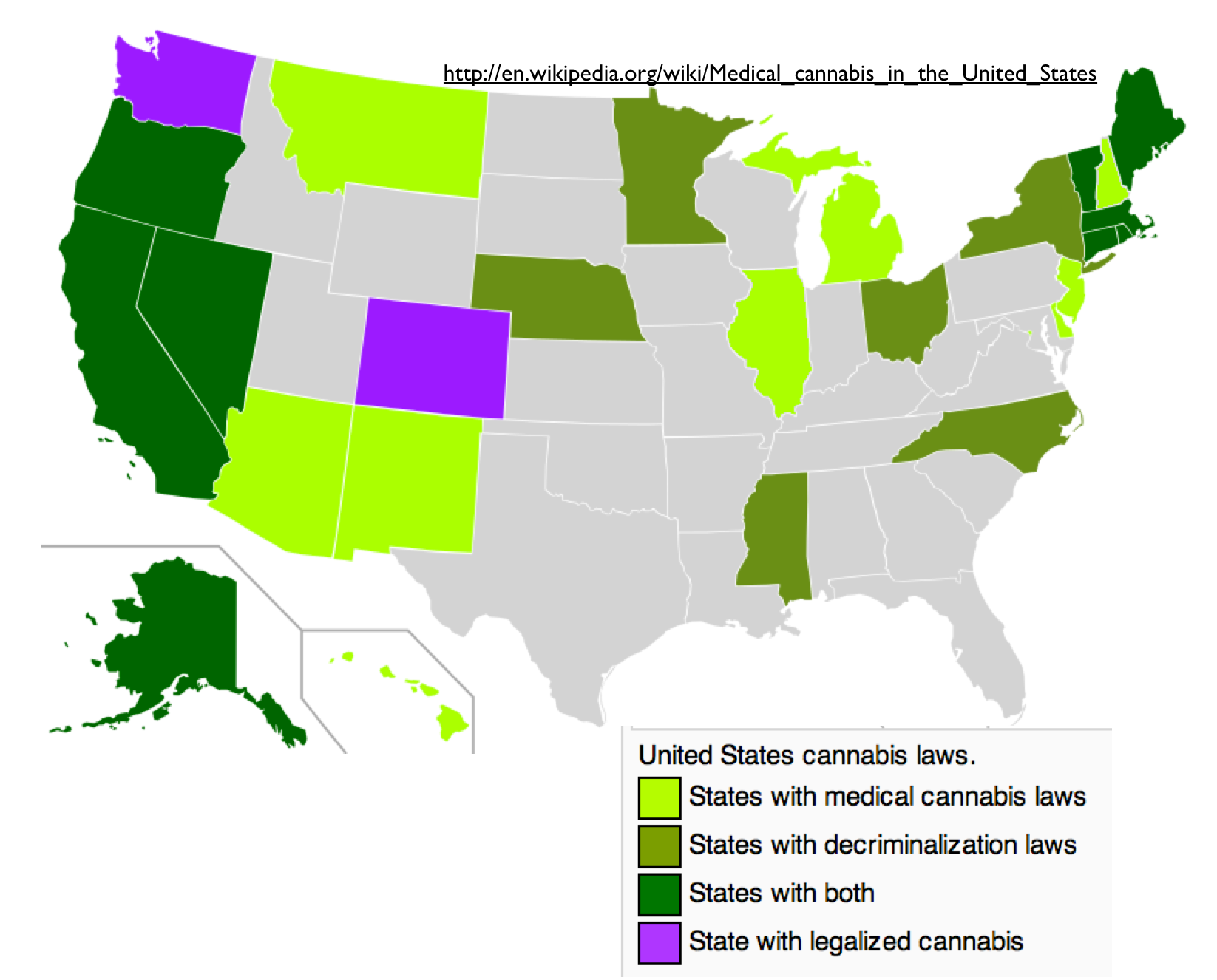

Over the past several years, the campaign for marijuana legalization has surged ahead in the United States. Colorado and Washington have voted for full legalization, and a number of other states now allow the consumption of medical cannabis. Yet the US federal government still regards the substance as a “Schedule 1” drug, more dangerous and less useful than cocaine or methamphetamine. The position of cannabis in American society is a deeply charged issue undergoing a sea change in the court of public opinion.

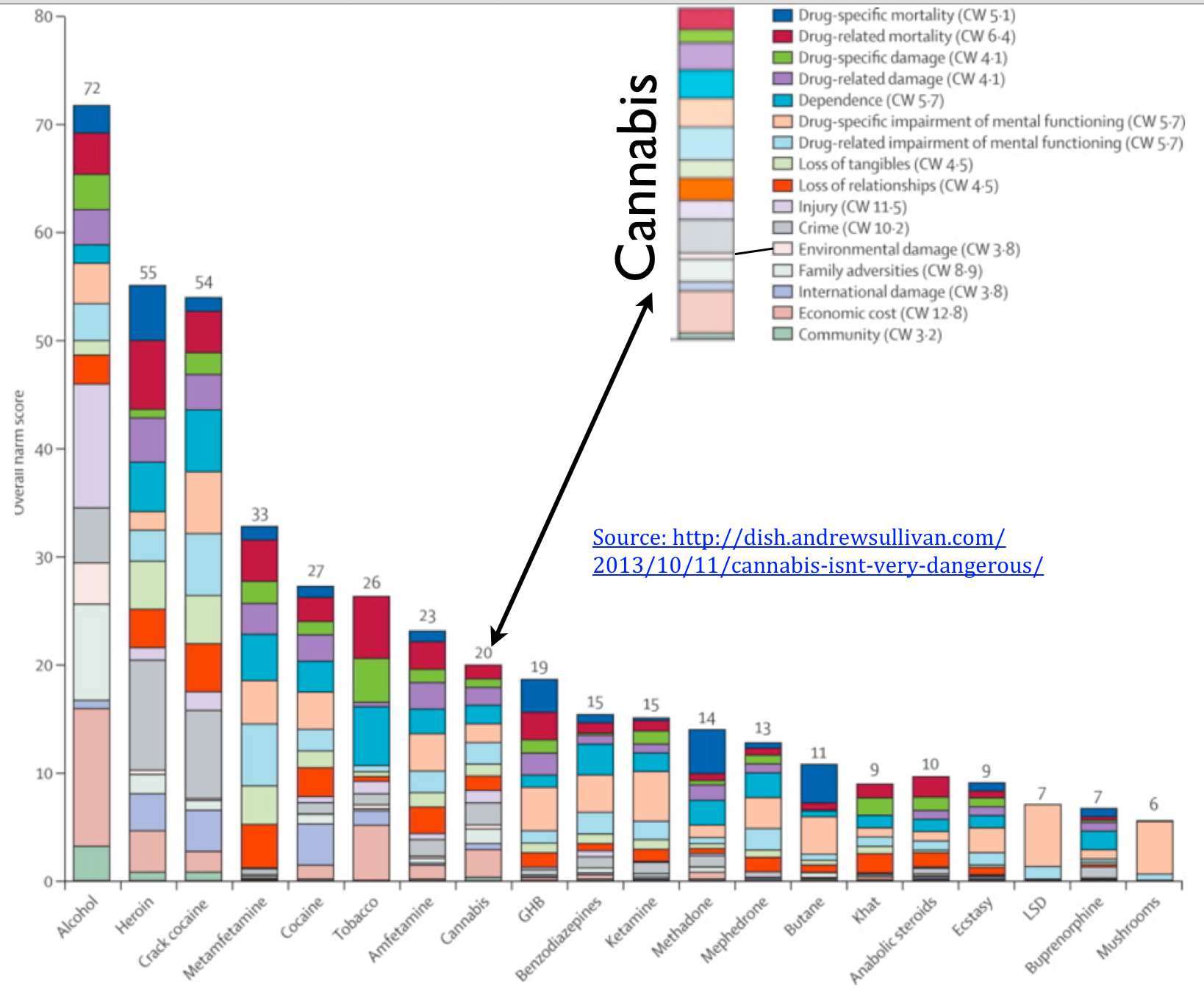

Marijuana legalization advocates make strong claims. By most objective measurements, cannabis is less harmful than alcohol from both a social and a medical perspective. But those who favor legalization would be advised not to overstate their case. As is true in regard to any substance, marijuana generates problems. Perhaps its most severe drawback is environmental damage, an inconvenient truth that is usually overlooked by legalization supporters. Consider, for example, the graph below, recently posted by the renowned blogger Andrew Sullivan. Sullivan is a proponent not only of marijuana legalization but also of its judicious use, as reflected in his book The Cannabis Closet. Although I am persuaded by most of Sullivan’s arguments, I think that he erred in posting this graph (below), which purports to show the extent of damages imparted by various drugs. Are we really expected to believe that alcohol is more harmful that heroin, cocaine, or methamphetamine? It would seem that the purpose is to shock rather than inform.

Although I am tempted to break down the graph and criticize its various components, I will confine my attention to one feature: the environmental damage of cannabis production. According to the figure, such costs are almost negligible, as can be seen in the inset illustration (which I have modified to highlight cannabis). In reality, the environmental damage imposed by marijuana growing is massive.

The most extreme form of environmental degradation associated with the cannabis industry stems from indoor cultivation. Growing indoors requires not merely intensely bright lights, but also extensive ventilation and dehumidification systems. The result is a gargantuan carbon footprint. According to a well-researched 2012 report:

The analysis performed in this study finds that indoor cannabis production results in energy expenditures of $6 billion each year–six times that of the entire U.S. pharmaceutical industry–with electricity use equivalent to that of 2 million average U.S. homes. This corresponds to 1% of national electricity consumption or 2% of that in households. The yearly greenhouse-gas pollution (carbon dioxide, CO2 ) from the electricity plus associated transportation fuels equals that of 3 million cars. Energy costs constitute a quarter of wholesale value.

Colossal energy use is not the only environmental drawback of indoor marijuana cultivation. Plants in such artificial environments are susceptible to a variety of pests and pathogens, often requiring heavy doses of biocides. Spider mites are a particular problem for cannabis producers. In order to prevent mold infestations, growers maintain low humidity levels, favoring mite proliferation. And as noted by the Wikipedia, “[their] accelerated reproductive rate allows spider mite populations to adapt quickly to resist pesticides, so chemical control methods can become somewhat ineffectual when the same pesticide is used over a prolonged period.”

Growing sun-loving plants in buildings under artificial suns is the height of environmental and economic lunacy. Outdoors, the major inputs—light and air—are free. Why then do people pay vast amounts of money to grow cannabis indoors, regardless of the huge environmental toll and the major financial costs? The reasons are varied. Outdoor cultivation is climatically impossible or unfeasible over much of the country. Everywhere, the risk of detection is much reduced for indoor operations. Indoor crops can also be gathered year-round, whereas outdoor harvests are an annual event. But the bigger spur for artificially grown cannabis appears to be consumer demand. As noted in a Huffington Post article “indoor growers … produce the best-looking buds, which command the highest prices and win the top prizes in competitions.” In California’s legal (or quasi-legal) medical marijuana dispensaries, artificially grown cannabis enjoys a major price advantage, due largely to the more uniformly high quality of the product.

Journalists have been noting the environmental harm of indoor marijuana cultivation for some time. Unfortunately, few people seem to care. In 2011, the San Francisco Bay Guardian reported that environmental concerns were leading some consumers to favor outdoor marijuana, but any such changes have not yet been reflected in market prices. In the cannabis industry, as in the oil industry, ecological damage does not seem to be much of an issue.

But even if indoor cultivation were to come to an end, the environmental harm of cannabis cultivation would not thereby disappear. Outdoor growing usually relies on heavy applications of chemical fertilizers, which can easily pollute waterways if not done correctly. Total water use is pronounced as well, which is an issue in the dry-summer cultivation areas of California. The most serious eco-threat, however, is posed by the rodenticides used to combat wood rats. These poisons endanger not merely rodents, but also the carnivores that prey upon them. In far northwestern California, the fisher (Martes pennanti)—rare to begin with—has been put in serious jeopardy by backwoods cultivators.

Cannabis can be raised in an environmentally responsible manner, as it often is by individual growers. Healthy outdoor plants suffer little damage from insects and other invertebrates. Mammals seldom eat the leaves, and wood-rat gnawing causes only minor damage in most areas. The highest yields, moreover, are obtained by those who avoid chemicals in favor of compost, manure, and biochar (buried charcoal). The liberal use of biochar, moreover, can actually generate a negative carbon footprint, as it involves sequestering carbon in the soil. Biochar is also one of the best long-term agricultural investments imaginable; the tierra preta soils of the Amazon, made by indigenous peoples before 1500, have maintained their fertility for centuries in an environment otherwise characterized by impoverished soils that cannot retain nutrients.

Given these advantages, why is organic cannabis cultivation in general, and the use of biochar more specifically, not more widespread? One crucial issue, which holds for organic farming the world over, is the amount of labor required, which is considerable. But equally important is the lack of consumer demand. In the cannabis market, relatively few buyers consider environmental costs, focusing instead on quality and appearance. And even those who do care about ecological consequences are thwarted by the impossibility of certifying sustainable production. Perhaps carbon-negative biochar-produced cannabis could command a price premium in some markets, but consumers have no way to know if such methods were actually used.

This situation is more than a little hypocritical. Both legalization advocates and the environmental community simply give a pass to some of the most environmentally destructive agricultural practices found on Earth. Pot consumers themselves tacitly support hyper-destructive “farming” by their eagerness to pay a premium for indoor product. Yet these same groups tend toward green politics, and many of their members are unforgiving when it comes to “non-sustainable” practices used by other farmers. Self-interest usually generates some level of moral blindness, but here it seems to be particularly pronounced.

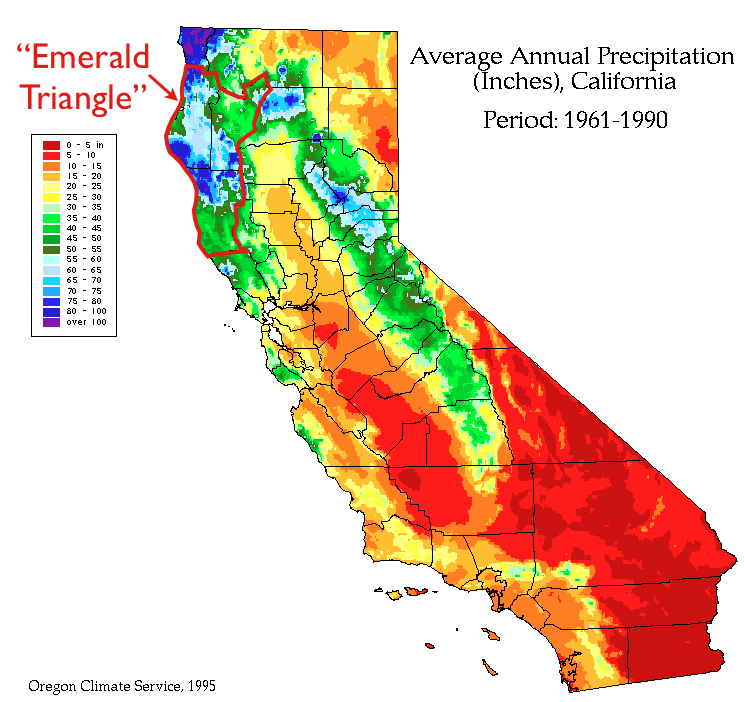

If cannabis cultivation in the United States were to move in an environmentally benign direction, California’s leading position would be greatly enhanced. California is unquestionably the top marijuana producer in the U.S., and the crop is without doubt the state’s most valuable. In his masterful 2010 Field Guide to California Agriculture, geographer Paul F. Starrs estimated the value of the California cannabis harvest at between $19 and $40 billion: if the former figure is correct, the crop is worth roughly half the value of all other agricultural products in the state; if the latter figure is accurate, then its value exceeds that of everything else combined. Due to climate, top-quality outdoor cannabis is difficult or impossible to produce in other states. Low humidity is required during the long maturation period in September and October; otherwise, mold infestations can rage out of control. Owing to its Mediterranean climate, California has favorable conditions, although in the prime growing counties of the Emerald Triangle, located in the wettest part of the state, mold is still the growers’ bane. As a result, cultivators welcome the Diablo Winds, warm dry easterlies that periodically blow in the autumn months. As is always the case, geography matters.

Martin Lewis is a senior lecturer in history at Stanford University. This post was originally published at the blog Geocurrents.

Photo Credit: San Francisco Sentinel