Fact Checking “The Language of Climate Politics”

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

When Ted Nordhaus first suggested that I write about some of the problematic claims that I’d come across while reading Dr. Genevieve Guenther’s The Language of Climate Politics, I wasn’t sure I wanted to do so, because I did not think the book merited a review.

But upon hearing some comments Dr. Guenther made in an interview promoting her book, I changed my mind. I had spent a good decade of my life, 2006-2016, fighting disinformation from climate science denialists, and it felt inconsistent to let the same slide just based on which “side” it was coming from.

So I agreed to write up a few of the problematic claims that had caught my ear as “must be wrong” as I walked my dog while listening to the audiobook. There are other errors, but life is short and I chose not to do a fuller factcheck. Hopefully, the following is instructive.

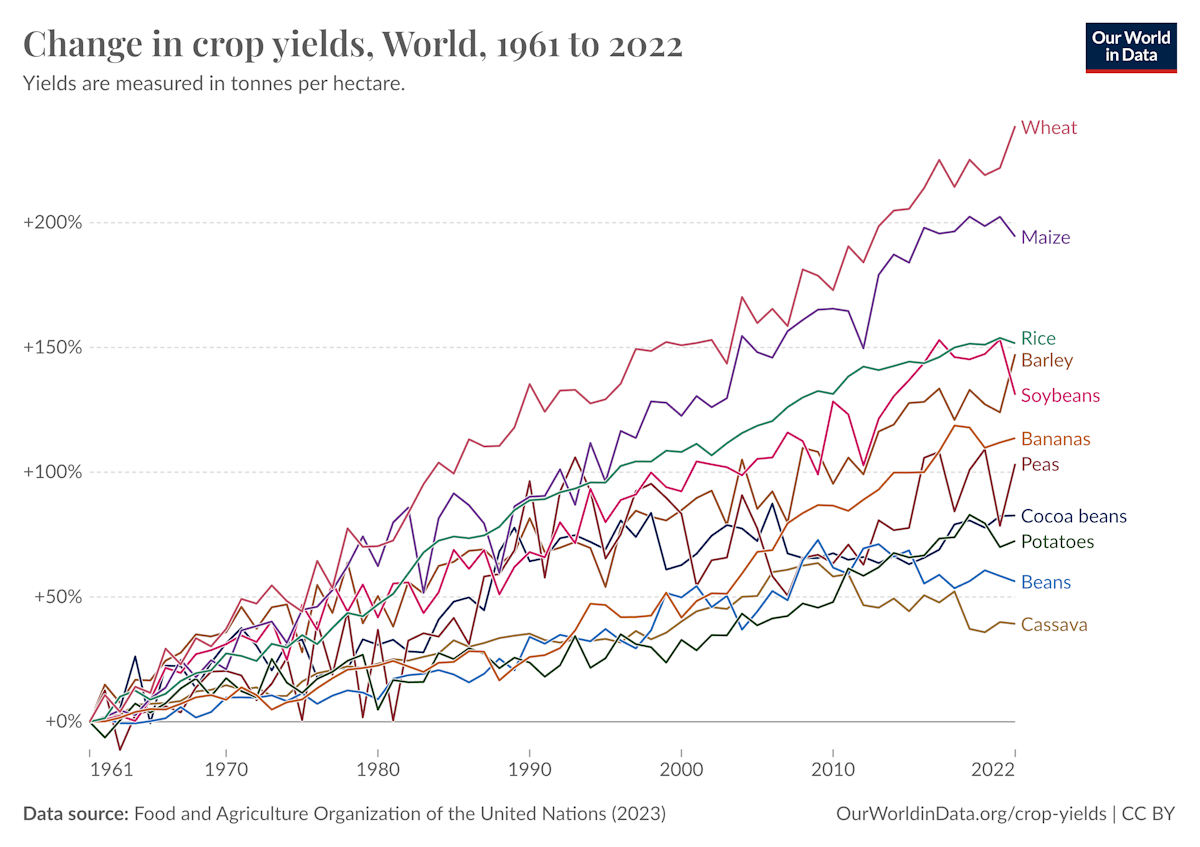

Claim 1. “Scientists at Cornell University recently discovered that the amount of food produced per acre of land has declined 21 percent globally between 1961 and 2021” (Guenther, pg. 101)

Guenther provides a seemingly solid reference to support this claim:

- Ariel Ortiz-Bobea et al., “Anthropogenic Climate Change Has Slowed Global Agricultural Productivity Growth,” Nature Climate Change 11, no. 4 (April 2021): 306–12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01000-1.

The problem is that the paper does not support her claim.

The Cornell authors were not estimating the absolute change in yield of global agriculture, as Guenther suggests. And they did not find—counter to Dr. Guenther’s claim—an absolute reduction in food yields. What they estimated is the effect that climate change had on the rate of *growth* of global agricultural productivity (i.e., yield per acre of land), relative to a simulated counterfactual case where there had not been any climate change at all. They found that global agricultural yield grew 21% less than it might have grown in the absence of climate change. But global agricultural yield did not fall 21% between 1961 and 2021 as Guenther claims.

To the contrary, it grew enormously. As illustrated by the graphics below from Our World in Data, global agricultural yields have increased by factors of 200 to 300% since 1961, depending on the crop.

Claim 2. “Wide-scale BECCS [BECCS = “bioenergy carbon capture and storage”] would also do terrible damage to ecosystems. One study warns that growing horizon-to-horizon acres of bioenergy (crops) ... would lead to ‘… ionizing radiation...’ In other words, it would… expose human bodies to DNA-severing electrons…” (Guenther, pg. 152)

Simply put, plants do not emit ionizing radiation.

So how does Guenther arrive at this odd claim? Again, her citation references a seemingly reputable source:

- Clair Gough et al., “Challenges to the Use of BECCS as a Keystone Technology in Pursuit of 1.5°C,” Global Sustainability 1 (2018): 3, https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2018.

But that paper only mentions “ionizing radiation” once, in the following statement: “(BECCS) may increase other environmental impact factors from different stages of the supply chain (e.g. ... ionizing radiation and ozone depletion).” (emphasis added). It does not tie “ionizing radiation” to growing bioenergy crops themselves, as Guenther claims.

So where, exactly, does the “ionizing radiation” come from?

Guenther’s reference in turn cites two other references:

- Carpentieri, M, Corti, A and Lombardi, L (2005) Life cycle assessment (LCA) of an integrated biomass gasification combined cycle (IBGCC) with CO2 removal. Energy Conversion and Management 46(11–12), 1790–1808.

- Schakel, W, Meerman, H, Talaei, A, Ramírez, A and Faaij, A (2014) Comparative life cycle assessment of biomass co-firing plants with carbon capture and storage. Applied Energy 131, 441–467. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.06.045

The first reference does not mention anything about ionizing radiation.

Only in the second paper, do we finally locate the source of the “DNA-severing electrons.”

The process of pelletizing biomass before it is used in co-firing power generation facilities requires additional electricity. Schakel, et al.’s lifecycle analysis assigns—as it should—additional environmental impact to the pelletization process commensurate with this additional electricity use. They look at the electricity generation mix in the country where the pelletization is done, and if some fraction of generation is from nuclear power, they make an estimate for how much extra ionizing radiation might be attributable to the electricity used in pelletization.

So the radiological health menace lurking in the proposed growing of bioenergy crops, which Guenther alleges will expose human bodies to dangerous DNA-severing electrons, turns out to be infinitesimal releases of ionizing radiation associated with the fraction of electricity generated by nuclear energy that would be used in the small amount of power required to pelletize biomass prior to its combustion and has nothing to do with “horizon-to-horizon acres” of plants.

Claim 3. “For BECCS to actually remove carbon from the atmosphere, 100 percent of the emissions from the bioenergy would need to be captured as it’s burned, or else the process would just keep emitting CO2 into the air, if at lower rates.” – (Guenther, pg. 150)

Guenther provides no reference whatsoever for this claim, which she apparently believes to be so self-evident that no reference is needed. But the claim in fact belies a fundamental lack of understanding of how the carbon cycle works.

Here, an instructive example is helpful. Imagine an end-to-end BECCS process that started with growing bioenergy crops incorporating, say, 10 million tonnes of carbon in its biomass. If that biomass were then burned for energy, with the CO₂ emissions then captured at a capture efficiency of, say, 50%, then the process would remove a net 5 million tonnes of carbon. The capture rate efficiency for a BECCS plant, in other words, contrary to Guenther’s claim, would not have to be anywhere near 100% to effectively remove large amounts of carbon from the atmosphere.

Guenther’s serial misunderstandings and misrepresentations of BECCS and other negative CO₂ emissions technologies, as documented above and below, are particularly notable, as her arguments against carbon removal are a central theme in the book and are often used to connect various advocates for technological solutions and innovation to what she claims are fossil fuel approved narratives of delay, disinformation, and denial. And so, BECCS, in Guenther’s telling, must not be simply a speculative solution with lots of technical challenges and potential for unintended consequences. It must, instead, represent an obviously false solution.

Claim 4. “We can see [that ‘climate policy recommendations based on the current framework seriously underestimate the economic value of climate damages’] simply by looking at the historical record. Nordhaus projects a loss of 1.62 percent of output per year at 3°C of warming, but between 2015 and 2018, for instance, at a little over 1°C of warming, the United States lost almost 2 percent of GDP in weather-related disasters.” – (Guenther, pg. 58)

Guenther’s claim here is not simply that future climate damage estimates in a recent version of William Nordhaus’ DICE integrated model of climate and economy are too low—a criticism that many others make as well. Guenther’s claim goes well beyond this, asserting that between 2015 and 2018, weather related disasters are already reducing US GDP by almost 2%.

This claim has a decidedly “must be wrong” feel to it, for those familiar with US weather disaster damages literature. Guenther, though, duly provides another seemingly credible source.

- Joseph Stiglitz, “The Economic Case for a Green New Deal,” in Winning the Green New Deal: Why We Must, How We Can, ed. Varshini Prakash and Guido Girgenti, First Simon & Schuster trade paperback edition (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020), pg. 96.

Stiglitz writes:

“The United States is already experiencing the financial costs of ignoring climate change—in recent years the country has lost almost 2 percent of GDP in weather-related disasters including floods, hurricanes, and forest fires.”

Stiglitz, in turn, on page 308 of the book, provides a note showing where he got his value from: “Extreme weather, made worse by climate change, along with the health effects of burning fossil fuels, has cost the US economy at least $240 billion a year over the past ten years. See Robert Watson, James J. McCarthy, and Liliana Hisas, ‘The Economic Case for Climate Action in the United States,’ Universal Ecological Fund FEU-US, September 2017” https://feu-us.org/case-for-climate-action-us/.”

The claim, now, is inclusive of “the health effects of burning fossil fuels,” not just weather-related disasters alone. Moreover, $240 billion a year is closer to 1%, not 2% of US GDP. And the period in question cannot be between 2015 and 2018, because the report that Stiglitz is referring to was published in 2017. Guenther appears to have just tacked on an additional year to Stiglitz’s original claim.

The claim, also, now comes not from Stiglitz himself or any of the readily available and less obscure sources in these subject areas, but from an advocacy group. And “losses to GDP” apparently now encompass all damages from weather related events—not just weather-related losses attributable to climate change—plus the health costs associated with conventional air pollutants resulting from the combustion of fossil fuels.

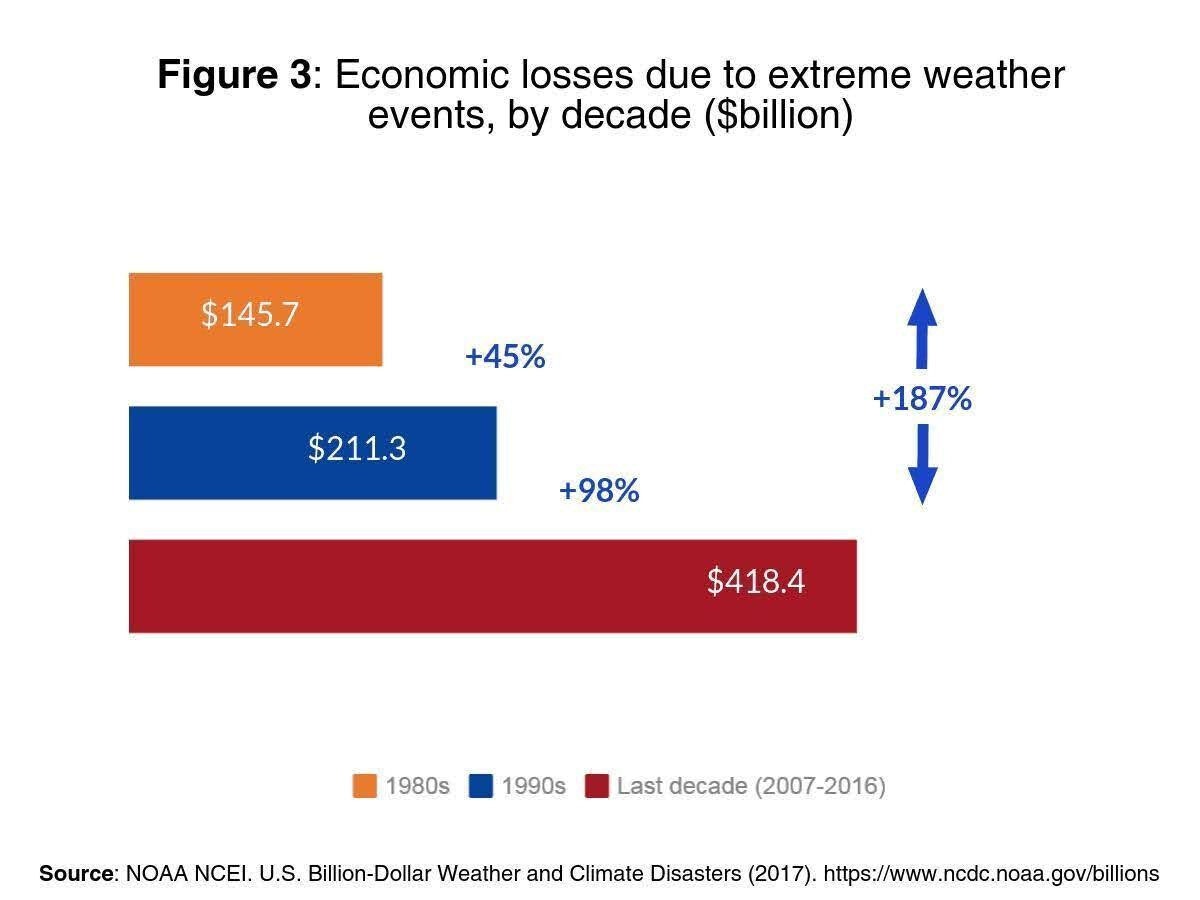

As it happens, the UEF study does break out damages from extreme weather events separately. Note that the figure below totals extreme weather damages by decade and ends in 2016, the year before the report was published. We still have no idea where Guenther comes up with an estimate for 2015-2018.

Here we see that the average US annual economic losses from extreme weather events over the previous decade (2007-2016) was $41.8 billion. This is closer to a number someone familiar with this subject would recognize as reasonable. US GDP during this period ranged from around $14-$19 trillion. So, these damages, as a share of US GDP, were actually around 0.2% of US GDP, not 2%, as Guenther claims.

And that is the total of all weather-related damages associated with extreme weather events in the United States during that period, not damages attributable to climate change, which would be a fraction of these costs.

Furthermore, the metric Nordhaus is estimating is GDP loss. That estimate refers to loss of economic output. The extreme-weather damages figure that UEF reports represents overall economic damages, which includes Direct Property Damage, Indirect Costs, Response and Recovery Costs, Environmental Impact, Healthcare Costs, and Economic Disruption. These itemized costs are often summed together and expressed as a percentage of total GDP, to give people a sense of the relative magnitudes. But only a relatively small fraction of these costs represent actual loss of GDP output. So UEF and Nordhaus are actually estimating quite different things. Even if one were to very generously assume that 50% of the UEF damages figure constituted lost output, it would further reduce the figure in question to a 0.1% GDP loss.

Moreover, Nordhaus is estimating loss of economic output attributable to climate change, not all weather related damages. So very generously assuming that one-third of those losses in the period covered by the UEF study were due to climate change, that would reduce the loss of output even further, to around .03% of GDP.

That is, a 0.03% loss of output today, give or take, that would be directly comparable to the 1.62% number Nordhaus estimates in the future.

Bill Nordhaus’ estimates of future damage to GDP due to climate change may well eventually prove an underestimate, but Guenther’s claim that they are already shown to be wrong by “simply looking at the historical record” is simply wrong. And her own sources do not support her claim.

Claim 5. “Avoiding this sickness and death—not paying this cost of fossil fuels, you might say—amounts to a healthcare and labor savings of over $700 billion per year, an amount of money that will pay for the majority of the transition to net-zero.” – (Guenther, pg. 69.) (bolding mine)

No reference specifically supporting this claim is given in the book, but one can surmise it almost certainly refers to this important Congressional testimony, which Guenther mentions shortly before in the book text:

- Shindell, Drew. “Health and Economic Benefits of a 2ºC Climate Policy”. Testimony to the House Committee on Oversight and Reform Hearing on “The Devastating Impacts of Climate Change on Health.” August 5, 2020. https://nicholas.duke.edu/sites/default/files/documents/Shindell_Testimony_July2020_final.pdf

The relevant section of Dr. Drew Shindell’s testimony that specifically quantifies similar dollar amounts is here:

“We find that there would be enormous benefits to the health of Americans from adopting policies consistent with the world’s 2ºC pledge. Over the next 50 years, keeping to the 2ºC pathway would prevent roughly 4.5 million premature deaths, about 3.5 million hospitalizations and emergency room visits, and approximately 300 million lost workdays in the US..."

“The economic value of these health and labor benefits is enormous. The avoided deaths are valued at more than $37 trillion. The avoided health care spending due to reduced hospitalizations and emergency room visits exceeds $37 billion, and the increased labor productivity is valued at more than $75 billion. On average, this amounts to over $700 billion per year in benefits to the US from improved health and labor alone, far more than the cost of the energy transition.” (highlights mine)

These do indeed represent huge potential non-climate benefits from moving away from fossil fuels.

But most of those benefits cannot be monetized as savings that might be available to pay for an energy transition. Only a tiny fraction of Shindell’s estimate—$37 billion from reduced health care costs and $75 billion in increased labor productivity spread over 50 years, could conceivably be put toward a transition to net-zero. The “health care and labor savings of $700 billion per year” which Dr. Guenther claims could be realized is actually only $2.1 billion per year.

The remaining $37 trillion—accounting for 99.7% of Shindell’s estimate—is based on a common economics statistical measure called “Value of a Statistical Life” (VSL). But, as Dr. Shindell goes to some effort to explain in his appendix, this is not a potential “savings.” It is calculated based upon surveys in which respondents answer a variety of abstract questions about how much they would theoretically be willing to pay to reduce the chance of premature death for themselves or others. It does not measure what costs people are willing to accept in order to reduce specific mortality risks. Nor does it measure how much the public would be willing to pay for an energy transition to avoid the consequences of climate change. Rather, based on these abstract calculations of the value of human life, it is an estimate of how much US citizens should be willing to pay—not save—over the next 50 years to avoid a cumulative excess premature 4.5 million deaths over that same period.

Moreover, Guenther herself explicitly rejects the most plausible mechanism through which such a calculation might be monetized such that the theoretical costs of those 4.5 million additional premature deaths might be “saved” and then invested in an energy transition, namely internalizing that cost through a price on carbon. One of many examples is:

“carbon taxes are ‘politically toxic,’ because they ask voters to bear the costs of both climate change and its resolution in the face of what is still largely inelastic demand for fossil fuels. Forcing consumers to pay more for fossil energy when alternatives are not yet readily available is to virtually guarantee political backlash.” (Guenther, pg. 90)

Voters, in other words, according to Guenther, are unwilling to pay the “costs”—namely a carbon tax—that might help achieve the potential benefits Dr. Shindell suggests are available, or which might raise public revenues that could be used to underwrite an energy transition.

Claim 6: “[I]nsofar as he [Solow] wondered what setting aside planetary boundaries in his model might say about the real economy or the world at large, he confined his speculations to a footnote, where he acknowledged that endless growth actually does depend on the planet—specifically on the endless production of new arable land via extraction from forests.” (Guenther, pg. 82)

Much of Chapter 3, titled Growth, revolves around the economist Robert Solow’s seminal 1956 paper, “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth,” which established the foundations of modern economic growth theory and for which Solow would win the Nobel Prize. Solow is cast as a villain in the book, along with his doctoral student, William Nordhaus, whose modeling of the costs and benefits of climate change and climate mitigation would ultimately win him the Nobel Prize as well.

Guenther makes much of a footnote early in the paper, on page 3 to be exact, which she uses to claim that Solow acknowledges that economic growth is limited by the availability of agricultural land. For Guenther, this supposed caveat looms large because agricultural land is, in her argument, a proxy for the planet. But Guenther either completely misunderstands or intentionally misrepresents what Solow is saying.

It is not coincidental that the footnote, which Guenther repeatedly returns to throughout her chapter, occurs in the opening pages of Solow’s 30 page paper. Solow is not suggesting that the ability to “hack land out of the wilderness at constant cost” is an assumption of Solow’s theory of growth. Solow has not even begun to expound upon his new model at this point in the paper. Rather, Solow is instead describing the implications of the leading Keynesian models of economic growth at the time, which he is critiquing. Those models, indeed, would require limitless access to land and other forms of capital accumulation at constant cost—otherwise they would be constrained by the old Ricardian frameworks for growth, where the availability of land, labor, and capital defined and limited the rate at which an economy could grow.

The footnote comes at the end of a sentence where Solow writes:

“The scarce-land case would lead to decreasing returns to scale in capital and labor and the model would become more Ricardian.2”

The footnote itself reads:

“See, for example, Haavelmo: A Study in the Theory of Economic Evolution (Amsterdam, 1954), pp. 9-11. Not all ‘underdeveloped’ countries are areas of land shortage. Ethiopia is a counterexample. One can imagine the theory as applying as long as arable land can be hacked out of the wilderness at essentially constant cost.”

Solow, above, is alluding to what he had earlier in the paper called “dubious assumptions” and “suspect results” in the existing Keynesian models—models he was specifically criticizing!

Solow was flagging that any valid explanation of long-run economic growth could not insist on “applying as long as land can be hacked out of the wilderness at essentially constant cost” because Solow didn’t believe that was how the real-world worked. And, since the world didn’t work that way, Solow was pointing out that the Keynesian models he was critiquing had had to assume away any “scarce-land case” because it indeed “would lead to decreasing returns to scale in capital and labor and the model would become more Ricardian.” The Keynesian models of economic growth Solow was challenging were implicitly assuming that no forms of capital—including land—would ever become scarce.

Solow would win his Nobel Prize by offering a theoretical framework that could account for sustained growth rates observed over the previous century that were far higher than the Ricardian model which was, indeed, limited to the growth of land, labor, and capital. In contrast, Solow’s theory posited that multifactor productivity growth was the primary driver of long term economic growth, and not only accounted for observed growth over the previous century at the time that he published it, but would prove to be explanatory of the observed economic growth over the almost 70 years since he postulated it.

Note from the chart above that global GDP, since 1960, has increased by a factor of almost nine without the world needing to hack more agricultural land, net, out of the wilderness. Without belaboring the point, this well-established fact is not limited to just the growth of agricultural land. The global economy since 1960 has grown at a rate well beyond what the growth of land, labor, and capital can account for.

There are many extant debates within the field of economics about how to best account for the value of ecosystem services and the present and future costs of climate change. These include issues like social discount rates and how to translate future temperature increase into economic damages. But Guenther’s, perhaps unwitting, return to Ricardian economics is most definitely not among them.

Claim 7. "3°C of global heating would likely mean that for around three months of the year, the entire East Coast all the way to Maine, the Midwest to the Great Plains... would be so hot that being outdoors would put you at risk of death... And that’s just the background heat." (Guenther, pg. 37)

This claim comes after several pages in which Guenther criticizes claims that high emissions and warming scenarios, until recently considered “business as usual,” are now increasingly implausible. Guenther’s complaint is not that those scenarios are in fact plausible but rather that more realistic scenarios suggesting that the world is presently on track for 2.5 or 3 degrees of warming instead of 4 or 5 degrees of warming would still be catastrophic.

The reference supporting Guenther's claim above is:

- Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers,” 2023, 14, Figure SPM.3, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6....

The source itself is notable in "The Language of Climate Politics": In a book with more than 600 citations, the authoritative IPCC Sixth Assessment Report of 2022-23 is cited just 10 times. But in this case, at the very least, IPCC AR6 does not support the claim she has made. What does SYR Fig. SPM.3 actually say?

The figure above does not suggest that a future with 2.4 - 3.1C of warming is one in which people living in Maine or Iowa would risk death from heat exposure simply by stepping outdoors during three months of each year. Rather, most of the regions Guenther includes in her claim will experience these conditions 1 – 10 days per year, with a few areas experiencing them somewhat more frequently. So Guenther’s claim of “around three months,” her own reference suggests, is an exaggeration of between 9x and 90x what is actually projected.

Moreover, if we look to the very far left of the graphic above, we see that much of the regions Guenther mentions, including much of the eastern seaboard and the midwest, already experience many days in which high heat and humidity create significant risks to human health and have for several decades. What the graphic shows is that as the planet warms further, the frequency of these types of days per region increases, as does the land area covered by the frequency shadings.

Notably, there is little change in the frequency or range of these high risk days between the 1.7 - 2.3 C warming graphic, which represents a future in which the world has had some significant success in limiting emissions and warming and the 2.4 - 3.1 C graphic which is, by most accounts, where the world is likely heading. In fact, coastal and temperate Maine turns out to be one of the few areas that does begin to experience high heat + humidity conditions in the latter 2.4 - 3.1 C graphic that doesn’t experience those same conditions in the 1.7 - 2.3 C graphic.

Finally, Figure SPM.3 does not in any way suggest, as Guenther claims, that simply stepping outside would put the average person at risk of death. The figure text suggests that on such days of the year where these heat and humidity conditions apply, there might be some risk of mortality to some individuals, which the figure acknowledges are “highly moderated by socio-economic, occupational and other non-climatic determinants of individual health and socio-economic vulnerability” and are projected “without additional adaptation.”

There are many good reasons to avoid 3°C of global surface warming. That is why the 2015 Paris Agreement sought to limit warming below that level. But risking death across large swaths of the midwestern and northeastern United States for the entire summer is not among them.

Claim 8. “Nor is there a one-to-one relationship between emissions and removals: if CDR managed to achieve net negative emissions, the ocean would start off-gassing the extra carbon dioxide that it has absorbed from human pollution, requiring the world to remove two billion tons to achieve a reduction of one billion tons of atmospheric CO₂.” (Guenther, pg. 160)

Most Earth Systems Models find a generally symmetrical response to positive and negative CO₂ emissions with respect to other parts of the Earth system, such as temperature or atmospheric CO₂ concentrations. It’s not perfectly symmetrical, because depending on the balance between ocean, land, and atmospheric carbon sinks, differing amounts of the carbon dioxide added or removed from the atmosphere may be taken up by other sinks. But that asymmetry is not anywhere close to 2 to 1 in favor of additions versus removals today, nor would it be under realistic conditions under which the world undertook a significant effort to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Guenther bases her claim on a single, very interesting paper that she clearly misunderstands.

- Kirsten Zickfeld et al., “Asymmetry in the Climate–Carbon Cycle Response to Positive and Negative CO2 Emissions,” Nature Climate Change 11, no. 7 (July 2021): 613–17, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01061-2

Zickfeld et al. do find that under very specific conditions there is a significant asymmetry in the impact of negative versus positive CO2 emissions. But to achieve that result, the authors had to push their Earth system model to quite extreme conditions relative to today.

How extreme?

In their main experiment, they first ran the model to full equilibrium with atmospheric CO₂ concentrations at 2x pre-industrial levels, or ~560 ppm. In order to do this, the authors first (slowly) added additional CO₂ emissions to the atmosphere significantly greater than all cumulative human CO₂ emissions to date, and then ran the model forward for 10,000 years, so that temperature, carbon pools and other parts of the system were fully equilibrated.

Then, they instantaneously forced the modeled system with truly staggering quantities of net positive or net negative CO₂ emissions, such as an instantaneous addition or subtraction of 500 GtC (1,830 GtCO₂), roughly equivalent to all cumulative human emissions since 1960.

Under these circumstances, with a doubling of pre-industrial atmospheric CO₂ fully equilibrated over 10,000 years and then an instantaneous removal of CO₂ equivalent to all anthropogenic emissions since 1960, Guenther’s claim is essentially correct: the ocean would indeed quickly off-gas in response, and, yes, you would need to remove ~2 tonnes of CO₂ from the atmosphere for any lasting change of 1 tonne of CO₂—just as you would need to add ~2 tonnes to get a similar 1 tonne change in the opposite direction. But this is not anywhere near the state that the earth system is actually in today, nor does it reflect how carbon might ultimately be removed from the atmosphere or how the earth system would respond to it.

Indeed, the very same lead author who Guenther cites above finds in a different paper that the response of the Earth system to positive and negative anthropogenic CO₂ emissions—occurring at near the conditions we are currently in—is in fact quite symmetrical to negative and positive emissions.

- Kirsten Zickfeld et al, “On the proportionality between global temperature change and cumulative CO2 emissions during periods of net negative CO2 emissions” 2016 Environ. Res. Lett. 11 055006 https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/11/5/055006

In Figure 1 from that paper, we see that atmospheric concentrations and temperature anomaly respond symmetrically to additions and removals. Not perfectly symmetric, but close, and nowhere near the 2:1 asymmetry suggested by Guenther.

- Katarzyna B Tokarska and Kirsten Zickfeld “The effectiveness of net negative carbon dioxide emissions in reversing anthropogenic climate change” 2015 Environ. Res. Lett. 10 094013 https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/10/9/094013

In this case, it appears that Guenther picked a single study—one that it is not entirely clear she even read, and that she certainly didn’t understand—to make a claim that is wildly inconsistent with consistent findings from earth system modeling, including more relevant and applicable modeling from the authors she cites.

REFERENCES

Friedlingstein, P., et al., Global Carbon Budget 2023, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 15, 5301–5369, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-1..., 2023.

Genevieve Guenther, The Language of Climate Politics: Fossil-Fuel Propaganda and How to Fight It (Oxford University Press, 2024) https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-language-of-climate-politics-9780197642238

Hannah Ritchie (2022) – “After millennia of agricultural expansion, the world has passed ‘peak agricultural land’” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/pea...’ [Online Resource]

Hannah Ritchie, Pablo Rosado and Max Roser (2023) - “Agricultural Production” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/agr...' [Online Resource]

Max Roser, Pablo Arriagada, Joe Hasell, Hannah Ritchie and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina (2023) – “Economic Growth”. Data adapted from World Bank, Bolt and van Zanden, Angus Maddison. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-gdp-over-the-long-run [online resource]

Robert Solow, “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 70, no. 1 (1956): 67. (available here: http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/Solow1956.pdf)