How Should We Interpret Chinese Critical Mineral Export Restrictions?

Unpacking the Cautionary Tale of the China-Japan Rare Earths Incident

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

Following the Biden administration’s recent expansion of restrictions on the sale of advanced semiconductor chip and manufacturing technologies to China, Chinese policymakers have responded rapidly by restricting exports of the critical minerals germanium, gallium, and antimony to the United States. Other new provisions, whose specifics remain unclear at the time of writing, may target additional materials like tungsten and graphite. This announcement comes in the wake of recent moves by Beijing to establish stricter export permit frameworks for a range of critical commodities including tungsten, graphite, magnesium, and aluminum alloys.

With U.S.-China trade tensions only likely to intensify in coming months, such raw material supply chain risks are becoming increasingly relevant for energy transition efforts as a whole. Other critical mineral export restrictions relevant for clean energy technologies could conceivably soon follow, with effects that may not be limited to the United States.

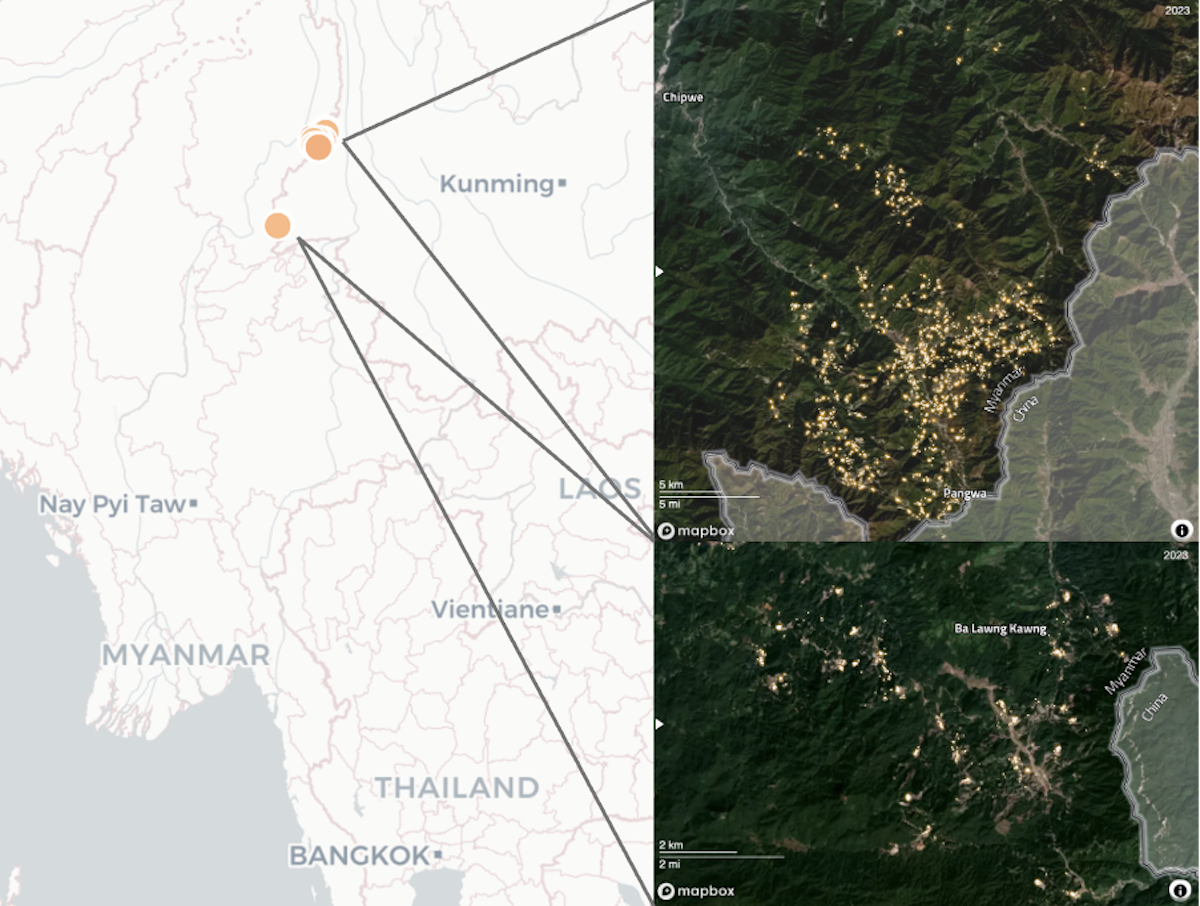

In Myanmar, for instance, resistance fighters from the Kachin Independence Organisation recently captured much of Pang War township, shutting down Myanmar’s largest rare earth mining hub and prompting Chinese authorities to close the nearby border crossing. Virtually unregulated mining in Myanmar contributes an unknown but large fraction of global rare earth element (REE) mining, with all of Myanmar’s production shipped to neighboring China, the world’s dominant refiner of rare earth materials. This latest development in a civil war turning increasingly in favor of anti-junta resistance groups has begun to send shivers through critical mineral markets, with industry observers speculating about a future rare earth shortage and price spikes.

If REEs become scarce, Chinese policymakers may clamp down on REE exports next to reserve more of these valuable critical minerals for domestic high-tech industries. Such restrictions could impose constraints upon the rest of the world, including overseas efforts to nurture clean technology sectors like wind power and electric vehicles that rely upon REEs for permanent magnet drives.

In response to critiques that clean energy sectors depend overly on key commodities imported from China, climate advocates and climate policy hawks have often argued that a country only needs to import battery minerals, solar panels, or electric cars once, at which point they escape the control of the exporting trade partner while operating for decades. This contrasts with continuous flows of fossil fuels whose interruption can immediately catapult energy supplies into a crisis. This reasoning is correct in principle, but supply chain disruptions would nevertheless stall acquisition—or manufacturing—of subsequent batches of low-carbon technologies. Such supply vulnerabilities can certainly freeze energy transition efforts in their tracks and force factories producing energy technologies to go idle.

The preeminent and most-invoked example of supply chain coercion remains China’s disruption of rare earth exports to Japan during the 2010 Senkaku Islands incident. A critical reexamination of this incident reveals a few useful insights that may help observers better understand these newest limits on critical mineral exports from China. The de-facto embargo in 2010 was likely opportunistic rather than planned—an impromptu exploitation of an issue prominent in preceding China-Japan negotiations rather than the culmination of some grand industrial geostrategic conspiracy. Yet this incident certainly cemented the perception that Chinese policymakers have and will wield control of strategic supply chains for geopolitical leverage—a concern that Beijing itself has reinforced since. These latest developments emphasize that policymakers and clean technology companies should be taking immediate steps to reduce supply chain vulnerabilities, if necessary even at what may seem like uneconomically high cost.

When Geopolitical Tensions Spill over into Supply Chains

According to conventional retellings, a number of Japanese companies reported a halt to expected rare earth ore shipments from China beginning Tuesday, September 21, 2010. This coincided with more overt political pressure tactics that had begun days prior, including a cessation of ministerial and provincial exchanges, a popular campaign to limit tourist visits to Japan, the detainment of four Japanese nationals in China, and an exclusion of Japanese companies from bidding on Chinese public projects. Many of these actions followed a Japanese government decision on September 19 to extend the detention of a Chinese fishing boat captain involved in collisions with two Japanese Coast Guard vessels near the Senkaku Islands on September 7.

Japan released the captain on September 25, and Chinese customs offices partially resumed clearing some REE shipments for export several days later. However, international traders, companies, and government officials continued to report systematic interruptions and delays for shipments to Japan as well as some U.S. and Europe-bound exports throughout October and the first half of November.

Following initial reports of blocked shipments by the New York Times and Nikkei on 23 September, Japanese government press conferences the next day on the matter produced a flurry of attention in Japanese and English-language press, at minimum including four Nikkei articles, three Asahi articles, and coverage in Reuters, France24, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, the Japan Times, and the Atlantic—all within a 24-hour period.

Asahi reporting from September 24 already described the situation as “appearing to be an effective embargo”, quoting a China-based REE manufacturing executive as having received instructions from Chinese customs officials to “stop exports until the 29th”. International customers including representatives of Australian, Canadian, Chinese, and Japanese firms all confirmed the suspension of shipments. Japanese government surveys of industry stakeholders in late September 2010 reported a clear consensus that export problems had increased after 21 September, driven by numerous sudden changes in Chinese customs enforcement. Out of 31 responding firms that confirmed their involvement in rare earths trade, all 31 reported encountering export obstacles. By Tuesday 28 September, Japan’s Minister for Economic and Fiscal Policy Banri Kaieda described the situation accordingly at a press conference: “Right now, the de-facto export prohibition that China has adopted is causing profoundly great impacts on Japan’s economy.”.

Notably, contemporary commentary showed a clear understanding that China had already slashed their REE export quotas a few months earlier, observing that the disruptions beginning in late September seemed separate and distinct from this earlier policy change. Articles by Toyo Keizai and Mitsubishi’s think tank MUFC published just days before the export halt very matter-of-factly articulated that China was reducing export quotas to nurture domestic industries, regulate foreign investment in the sector, and limit expansion of new mining for environmental reasons. Reporting from September 25 highlighted arguments by industry observers that they wouldn’t expect producers to exhaust their export quotas until late October at the earliest, with traders noting that even Chinese producers with ample spare export quotas had “been dissuaded” from exporting. In subsequent interviews with researchers, Japanese officials confirmed an internal understanding at the time that the central Chinese government had issued an order, and that the Japanese government interpreted the incident as an economic sanction.

These contemporaneous official government statements, media reporting, comments from industry, and policy responses across English, Japanese, and Chinese-language sources shared a clear understanding that Chinese officials had implemented a de-facto export ban, prompting many governments worldwide to lodge protests while urgently pursuing supply chain alternatives and countermeasures. Even a Chinese People’s Daily article from late 2012 more or less stated: “Even though China did not publicly admit to employing economic sanctions, China did in reality halt export shipments, subjecting Japan to some difficulties at the time”.

How Real were the Impacts on Rare Earth Element Trade?

Some work in late 2010 and since has challenged this prevailing storyline, arguing that this period of scarce supply and price spikes beginning in late 2010 did stem mostly from China’s stricter export quotas imposed in July—a policy action well predating the diplomatic dispute. Such commentators argue China’s export policies sought only favorable domestic economic outcomes—more stringent environmental regulation of the REE sector and better capture of value-added downstream industries. Revisionist retellings at times go even further, arguing that any resulting supply shortages in late 2010 did not explicitly target Japan and warning against invented narratives of Chinese mineral supply chain coercion. However, such interpretations stray from the historical record and often overstate their case.

Commentators arguing that China’s undeclared interference in rare earth trade in late 2010 is exaggerated “folklore” have often cited a few articles that analyzed monthly Japanese customs or UN data on value of trade in various goods, claiming that overall, broad categories of rare earths traded with Japan do not seem to exhibit quantitative disruptions during this period. However, such low-resolution, indirect data does not distinguish between far more valuable heavy rare earth elements important for high-tech applications versus more abundant light rare earths like cerium that primarily see use in more mundane industrial processes.

Overall, the cited data don’t contain enough detail to draw a clear conclusion that no significant disruptions occurred. Summary data on total rare earth shipment arrivals in Japan might conceal a decline in imports from China compensated by urgently redirected materials sourced from Southeast Asia, Europe, or North America. Similarly, indirect metrics like the monthly value of rare earth shipments from China to Japan may not accurately capture simultaneously evolving variables, like a decline in import tonnage offset by a corresponding spike in rare earth prices. Moreover, monthly-scale data may not confidently capture shorter-term disruptions and delays that began towards the end of September 2010 and varied from week to week thereafter. Finally, such sterile retrospective analyses of trade data in isolation ignores a vast weight of contemporaneous, corroborating testimony and reporting, such as the official surveys of affected industries.

One should also recall that broader Chinese economic coercion aimed at Japan in late September 2010 was not seeking to damage Japan materially so much as to accomplish a specific goal: the successful release of the detained fishing boat captain.

It is true however that China did dramatically alter export and industrial policies for the rare earths sector earlier in 2010. These changes indeed stemmed in part from domestic environmental considerations and aspirations to further develop downstream value-added industries like rare earth permanent magnet manufacturing. And while the particularly sharp reduction in export quotas in July 2010 generated significant international attention and discussion for months predating the Senkaku islands dispute, Chinese national policy had long treated REEs as a strategic commodity and regularly revised regulations and export practices over the years.

While rare earth elements are widely distributed globally, southern China hosts a notable concentration of ion adsorption clay (IAC) deposits, located at relatively shallow depths and mineable using simpler methods in small-scale operations. These deposits tend to form in temperate or tropical climates with higher temperatures and rainfall that can leach REEs from bedrock and concentrate them in clay soils. IAC deposits typically contain higher grades of heavy REEs relative to hardrock REE deposits, may not require onsite milling, and allow for initial processing onsite using pit leaching, often using ammonium sulfates. Such low-cost IAC mining operations have driven much of the growth in China’s rare earth sector over recent decades, albeit with considerable environmental impacts that have prompted stricter regulations since the mid-2010s.

Starting in 1985, the Chinese government began offering an export rebate to REE enterprises to encourage rare earth exports, refunding the value-added tax that producers paid on exported products. Following China’s overtaking of the United States as the world’s largest REE producer in the late 1980s, Chinese policymakers designated REEs as strategic minerals as early as 1990, with national production ramping up dramatically through the 1990s thanks largely to growth in small-scale projects targeting IAC deposits. By 2000, in light of increasing domestic industry demand for rare earths, the central government reduced export rebates before eliminating them altogether in 2005. With the subsequent introduction of export duties for rare earths in 2007, China’s export strategy had entirely reversed. Policymakers had already implemented export quotas years earlier in 1999 to control total national production and curb smuggling, and would progressively reduce quotas every year between 2005 and 2010.

The dramatically lowered export quota announced in mid-2010 may very well have contributed to the continuing customs delays and export disruptions throughout October and November that year. But the intensity and timing of events in late September coincided far too closely with the China-Japan diplomatic crisis to discount as a bureaucratic coincidence. Even Chinese commerce minister Chen Deming drew a link between the two issues in a televised interview on 26 September, suggesting that Chinese businesses might be acting on their own patriotic initiative to pause shipments.

International governments certainly interpreted this rare earths shock as an undeclared set of sanctions. In retrospect perhaps these trade disruptions appear short-lived to observers today, but in the moment the affected actors saw these measures as indefinite and reacted with alarm. By October 3rd, Japanese officials were negotiating with the Mongolian government to develop new rare earth mining projects in Mongolia. By late October, Japan and Korea had announced a partnership in which Japan would help Korea survey potential deposits. Within a couple months, the United States and Japan were exploring projects in California, Australia, and Indonesia.

Implications of China’s Recent Export Restriction

Chinese policymakers likely weaponized rare earth exports opportunistically in the moment. The framework for export limits did genuinely originate out of industrial policy crafted with China’s national interest in mind, and well predated the tensions that prompted their temporary weaponization. Japan and China had been negotiating specifically over rare earth export quotas earlier in the year—including just weeks beforehand. With the issue fresh in recent memory, Beijing policymakers understood full well that this was a powerful lever in China-Japan relations.

The 2010 rare earths disruption and the current situation now unfolding between China and the United States share some similarities but also exhibit notable differences. As in 2010, the new Chinese export restrictions on gallium, germanium, and other critical mineral shipments to the U.S. clearly form part of a planned tit-for-tat response to the latest U.S. restrictions targeting the Chinese semiconductor industry manufacturing chain. In contrast to the 2010 incident, however, Beijing’s leverage of critical mineral supply chains is now overt and explicit, rather than ambiguous. Furthermore, whereas disruption of rare earth shipments to Japan may have served a narrow, temporary geopolitical purpose, U.S.-China competition for advanced technology leadership clearly spans a far broader scope, with no simple or near-term resolution in sight.

Meanwhile, with China now operating export control frameworks for everything from tungsten to magnesium to rare earth concentrating equipment to solar manufacturing machinery, the possibility of further escalation looms large—with significant implications for clean technology supply chains and trade.

The lesson from the 2010 rare earths shock and its origins emphasizes that Chinese export controls on critical minerals likely originated out of narrow national economic self-interest, rather than serving as part of some grand strategic conspiracy. But fundamentally speaking, the combination of overwhelming market share control and absolute authority over export policies means that Beijing can control market supply and international prices for a wide host of critical commodities with the stroke of a pen, an ability whose geopolitical utility is clearly now obvious to Chinese leaders. Should the right situation arise, the tools for bottlenecking trade already exist, including substantial latitude for subtle, undeclared, and plausibly deniable economic coercion in addition to the overt measures now enjoying the spotlight.

The only solution to this dynamic of self-perpetuating Chinese critical mineral market overconcentration is a forceful strategy of supply chain expansion and diversification. Such a strategy must dispense with the futile practice of tepidly ushering new entrants into unforgiving markets built upon lopsided terms of competition. Rather, governments must stubbornly and persistently ensure that alternative producers survive and multiply—in and of itself a necessary prerequisite for fostering competition and breaking monopoly power.

Ultimately, the world’s access to crucial advanced energy technologies cannot depend upon some People’s Liberation Army Air Force pilot’s ability to execute a reckless aerial maneuver around a Taiwanese patrol aircraft. The ease with which even the most optimistic clean energy commentator can imagine such a contingency should stress that both the geopolitical and decarbonization stakes of such efforts are high.