Technology Policy, Not Emissions Policy

An IRA Reform Proposal

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

Congressional Republicans will likely seek to repeal significant portions of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) under reconciliation procedures this term, to offset the budgetary cost of extending the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act and other fiscal measures. Climate and clean energy advocates have raised the alarm over the threat posed by this repeal to clean energy sectors, however, targeted reforms could substantially reduce the cost of the IRA while continuing to support energy innovation.

The bulk of estimated federal expenditures under the IRA are projected to go to the most mature low-carbon technologies: solar photovoltaics, onshore wind, and electric vehicles. These categories account for up to 60% to 80% of anticipated spending over the 2025-2034 period. By contrast, incentives for less mature technologies, like green hydrogen, carbon removal, and advanced nuclear reactors, are projected to cost much less over the next ten years. Repealing public incentives for promising but less mature sectors would greatly imperil technological progress and U.S. competitiveness without saving much in the way of federal expenditures.

This question of technological maturity should guide policymakers’ decision-making as they consider whether and how to reform the IRA. Many early discussions and proposals for scaling back energy-related tax credits simply weigh repealing provisions entirely versus maintaining them as written, or consider phasing out existing incentives nationwide within the next few years. Such efforts may benefit from a more strategic, targeted redesign that can achieve comparable fiscal savings while refocusing public spending towards technologies and projects with high innovation value.

We propose a different approach to reforms to the energy provisions of the IRA, as articulated in the table below. The major changes proposed here focus on the Section 30D New Clean Vehicle Tax Credit for consumers and the Section 45Y and Section 48E “technology-neutral” tax credits for clean electricity production and investment. In total, these revised tax credit structures can realize significant fiscal savings of nearly $421 billion dollars while continuing to prioritize U.S. energy technology leadership and critical minerals supply chain security.

45Y Clean Electricity Production Credit and 48E Clean Electricity Investment Credit

45Y and 48E currently phase out nationwide when the Secretary of Energy determines annual power-sector carbon emissions have declined below 25% of 2022 levels, or phase out in the year 2032, whichever is later. This is a perverse incentive structure, threatening the energy system with two important economic distortions: excessive spending on subsidies for commercially mature technologies, and, the subsidization of technologies to the point of imposing price volatility and reliability impacts upon the grid.

The first distortion is already evident. Solar PV and onshore wind comprise the majority of new growth in both U.S. electricity generation and installed capacity, as well as the bulk of projects in the interconnection queues of all major U.S. grid regions. Solar panels and wind turbines are affordable, modular technologies with sophisticated and globalized supply chains and healthy commercial interest across the country.

The second distortion is less acute but becoming more concerning in some grid regions. As intermittent solar and wind grid penetration increases, their marginal value to the grid decreases. Given this widely understood problem of value deflation, federal tax credits pegged to deep emissions targets, as opposed to some measure of commercial maturity or grid penetration, run the risk of subsidizing increasingly uneconomic wind and solar projects. Pushing these sectors to develop well beyond their equilibrium in competitive electricity markets results in electricity grids where a large fraction of generation becomes highly correlated based on spatial and temporal weather patterns. Meanwhile, baseload generation like hydropower, nuclear, and geothermal in such regions risks distorted revenue losses, while accompanying flexible generation from gas bears increasing sensitivity to infrastructure vulnerabilities, gas price volatility, and supply chain constraints such as long lead times for gas turbines. Promising growth in grid battery storage can forestall such challenges but cannot eliminate them entirely without cost-inefficient levels of deployment. Such dynamics pose risks to the reliability of regional electricity systems which could even backfire upon the wind and solar sector.

Pegging subsidization to grid penetration, by contrast, would prevent hundreds of billions of dollars from being spent on mature technologies and avoid market dynamics that push wind and solar beyond value deflation constraints. Rather, federal spending would rightly rebalance support towards technology deployment in less saturated markets, as well as deployment of promising but less mature technologies.

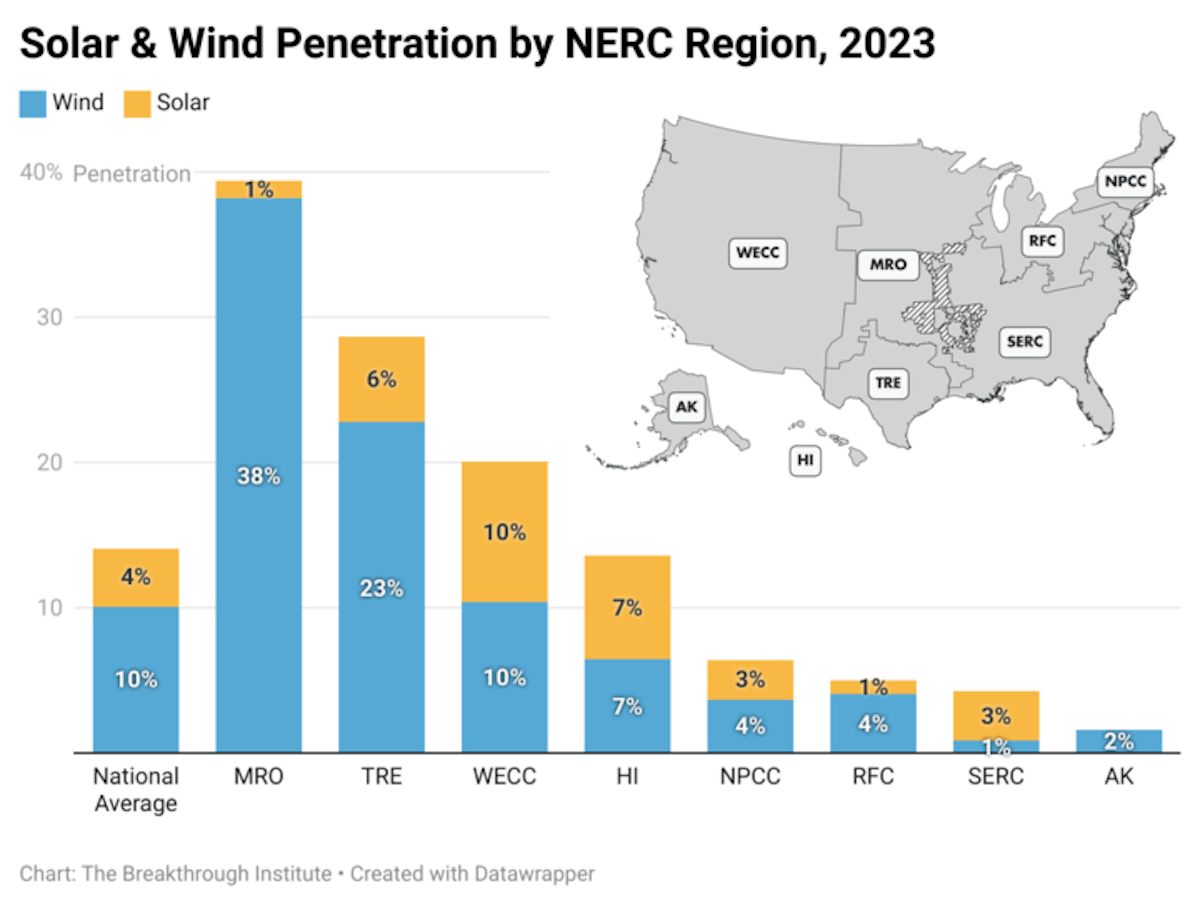

We propose phasing out Section 45Y and 48E credits for individual generation technologies when a given technology exceeds 5% of utility-scale generation within a given North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) region. We estimate that such suggested changes to 45Y and 48E would reduce total federal spending on these credits to $60 billion, a decrease of roughly $361 billion, relative to the Treasury estimate of $421 billion of clean electricity credit spending over the 2025-2034 period and corresponding to an 86% reduction.

After the year in which a technology first exceeds this threshold and triggers credit phase-out, the credit would phase out over the next three years as currently articulated in the IRA for the production and investment credits: 100% credit eligibility in the first following year, 75% of the credit in the second year, 50% of the credit in the third year, and nothing thereafter. Small-scale projects under 1 MW in installed capacity and large projects over 1 MW using the same generation technology would both count towards this same 5% threshold for a regional phaseout of the credits.

As Figure 2 below illustrates, this would make both solar and wind eligible for continued subsidies in some regions and ineligible in others. The same 5% cap would apply to other, less-mature low-carbon technologies, including geothermal, offshore wind, and new commercial nuclear reactors, though it is unlikely many of these technologies would exceed the cap within the next decade.

We argue that Congress should not apply a regional threshold-based phaseout for credits in the Hawaii and Alaska NERC regions as well as in U.S. territories but rather phase out these credits after 2032. Hawaii, Alaska, and U.S. territories will account for a relatively negligible share of program-related spending, and these states and territories represent strategically vital U.S. regions that face greater energy system resource adequacy and reliability challenges than the U.S. mainland.

We disagree with proposals to retain the production tax credit while eliminating the investment tax credit, as suggested in some proposed IRA reform approaches. The ITC possesses far greater importance for nascent, emerging, but promising clean energy technologies like advanced nuclear and advanced geothermal power, by supporting crucial early deployment of higher-cost initial commercial projects. The ITC also naturally scales downwards in magnitude as deployed technologies become more affordable. If anything, policymakers should direct greater scrutiny towards the PTC, which provides a flat subsidy per unit of generated electricity regardless of technology maturity and directly affects the dynamics of electricity market economic dispatch.

Importantly, we would maintain the 48E investment tax credit for energy storage technologies. Storage technologies do not currently confront the same risks of decreasing marginal value on the grid, and in fact help mitigate value deflation problems facing wind and solar in some regions. Storage plays useful general market roles in banking grid electricity when it is abundant and releasing it to consumers when electricity is in higher demand as well as in provision of supporting ancillary grid services key to grid reliability. Many emerging energy storage technologies like thermal, iron-air, molten salt, or compressed air energy storage are also not yet technologically mature, with investment tax credits playing an important role in early commercialization and demonstration.

45U Zero-Emission Nuclear Power Production Credit

The Section 45U tax credit for operating nuclear power plants would be maintained at its current level. The 45U credit applies only to nuclear power plants in merchant markets under threat of premature closure from other policy or economic pressures.

30D Clean Vehicle Credit and 45W Qualified Commercial Clean Vehicle Credit

The Clean Vehicle Credit and Commercial Clean Vehicle Credit subsidize two already widely commercialized technologies—electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid vehicles. These credits also apply in principle to hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, a less mature category of low-emissions vehicles that has struggled to achieve widespread adoption, and would also apply to innovative emerging vehicle concepts such as extended-range electric vehicles (EREVs). The 45W Commercial Clean Vehicle Credit also provides tax incentives for the purchase of heavier electric vehicles such as freight trucks, school buses, and mine trucks. Estimates of the spending associated with these EV tax credits over the next 10 years range from $96.6 billion to $286.7 billion.

These clean vehicle credits do support important national interests by creating demand for U.S. critical mineral projects and advanced vehicle component manufacturing, helping strengthen U.S. technical expertise and investment in key technological capabilities like direct lithium extraction, battery chemical production, and high-quality metallurgical castings. The domestic critical minerals and domestic component assembly provisions of the 30D Clean Vehicle Credit create a direct business incentive for U.S. automakers to source raw materials and parts from American firms. These domestic sourcing provisions have played a direct, demonstrable role in capitalizing strategically-valuable projects like the Talon Metals nickel mine in Minnesota and the Thacker Pass lithium mine in Nevada.

These credits can be significantly narrowed and improved to focus exclusively on promoting American critical mineral supply chain and manufacturing investments, dramatically reducing the majority of total spending while maximizing economic, security, and competitiveness benefits to the American people. Our proposals are as follows:

- Close the 45W leasing loophole. The Commercial Clean Vehicle Credit currently allows for leased electric vehicles to qualify, allowing leased passenger electric cars to circumvent the domestic critical minerals and domestic component assembly requirements that apply to the 30D Clean Vehicle Credit. This contradicts Congress’s original vision for the clean vehicle credits, which were meant to focus incentives on electric vehicles that utilize U.S. manufacturing and mineral supply chains. Some major U.S. electric vehicle manufacturers currently lease as many as 40% of the EVs that they currently supply to the U.S. market. Closing the leasing loophole represents a considerable reduction in subsidy spending while dramatically refocusing the subsidy on spurring U.S. critical mineral and component assembly projects as originally intended by Congress. The Ways and Means committee estimated the leasing loophole closure to be worth $50 billion in 10-year savings.

- Limit domestic component assembly credit eligibility requirement to U.S. based assembly only. This removes the current allowance for free trade partner eligibility. Treasury should issue guidance to establish a new de minimis threshold for overseas imported components to reduce cases where vehicles fail to meet eligibility due to import of very minor components comprising a negligible fraction of the vehicle’s market value.

- Require clean vehicles seeking the credit to meet both the domestic critical minerals and domestic component assembly criteria to qualify for the credit. This entirely eliminates the current option for partial clean vehicle credit eligibility.

- No change to domestic critical minerals credit eligibility requirements.

By eliminating the 45W leasing loophole and more importantly substantially tightening the stringency with which domestic component assembly and domestic critical mineral criteria are applied to determine credit eligibility, we anticipate these reforms will shrink IRA clean vehicle credit spending by at least $60 billion compared to Treasury’s projected future spending under the law as it exists today ($105.7 billion over the 2025-2034 period). At the same time, this refocusing of vehicle tax credits will maximize national strategic benefits by devoting remaining spending to explicit support of domestic manufacturing, critical mineral supply chains, and related economic activities.

45Q Credit for Carbon Oxide Sequestration and 45V Credit for Production of Clean Hydrogen

Our proposal would also maintain the Section 45Q Carbon Sequestration credit. Unique among IRA tax credits, 45Q actually offers an incentive pegged to marginal, not absolute, emissions reduction. If Congress maintains that reducing emissions is worth $60-180 per ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (depending on the form of sequestration), then this credit should stand in perpetuity. Carbon dioxide sequestration technologies have not yet achieved widespread commercialization and deployment. Incentives that promote the development and deployment of such technologies position the U.S. for leadership in an increasingly important sector poised to grow as society places increasing value on reliable, verifiable, long-term carbon sequestration. Most government and third-party federal budget estimates also gauge future spending associated with the 45Q credit to be small relative to clean electricity and clean vehicle incentives.

Our suggested reform framework would also maintain the 45V clean hydrogen production tax credit. Like 45Q, the 45V clean hydrogen credit supports technology-neutral development of innovative approaches for hydrogen fuel production from electrolysis, carbon capture, refining of biogas and biomass feedstocks, and from natural geologic resources. These technologies similarly have yet to reach full commercial viability but offer valuable strategic technology leadership opportunities while bolstering future U.S. energy resource abundance. Stringent guidance on 45V credit eligibility and slower-than-anticipated cost improvements in hydrogen electrolyzer systems mean that this credit probably represents a less significant spending factor than originally estimated. As with 45Q, the magnitude of 45V-related spending is also far smaller than the level of spending associated with clean electricity and electric vehicle credits (Figure 3).

45Z Clean Fuel Production Credit

EPA’s recent Triennial Report to Congress on biofuels finds that the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) has likely had negative environmental impacts, increased corn and soy prices, and thereby slightly increased meat and dairy prices. Congress should repeal subsidies for first generation crop-based biofuels such as corn ethanol that have received tens of billions of dollars in federal support over decades and are now well-developed technologies. Conservative estimates expect repeal of the 45Z Clean Fuel Production Credit would save $12.78 billion over 2025-2034. These funds should instead be reallocated to support farmers to grow food and livestock feed more efficiently and expand international markets.

Section 21001 Additional Agricultural Conservation Investments

The Inflation Reduction Act provided $19.5 billion to support climate-smart practices through NRCS conservation programs, like EQIP and CSP. This funding is available through 2027. Whether via new Farm Bill legislation or in a reconciliation bill, Congress should remove the climate guardrails attached to the remaining unobligated funds, given that the previously obligated funding has gone toward practices that reduce yields and offer little in terms of permanent climate mitigation, and add the funding to the baseline of the Farm Bill’s conservation programs. Congress should allocate remaining funds to practices under these programs that improve productivity.

Neutrality is a Technology Policy Tool, not a Tenet

In total, our proposed reforms likely save on the order of $421 billion in federal spending.

The IRA’s expansive technology incentives are a feature, not a bug, of the law. Separate, targeted credits for vehicles, electrolyzers, carbon sequestration, low-carbon fuels, and existing nuclear power plants make sense. And the technology-neutral 45Y and 48E credits are an improvement upon the pre-existing PTC and ITC as well as state-level renewable portfolio policies, which for too long excluded technologies like advanced nuclear reactors.

Technology-neutral policies and regulations offer many advantages. The technological future remains difficult to predict, and policymakers do not know a priori whether competing approaches for producing low-emissions hydrogen from electrolysis or from methane with integrated carbon capture will achieve technological and market advances faster. In regulatory policy, technology-neutral rules that focus on quantifiable performance metrics like public health benefits or structural resilience often yield better and more efficient regulatory systems than efforts to meticulously craft separate sets of rules for a spectrum of technologies constantly entering the market or becoming obsolete, as our work on U.S. nuclear regulatory policy consistently emphasizes.

But technology policy cannot remain neutral to the point of inefficiency. Subsidies as a tool for technology policy are most valuable when leveraged to maximize innovation, and the innovation policy needs of microreactors and enhanced geothermal power plants are simply a world apart from the needs of the now mature, large-scale solar photovoltaic and onshore wind sectors. To the extent that these diverse technology sectors benefit from the same federal subsidy, policymakers’ goal should be to prioritize bootstrapping nascent industries into commercially mature sectors of the American energy economy. Such a strategy requires a targeted and regularly evolving mix of technology-inclusive and technology-specific subsidies, not functionally perpetual technology-neutral spending.

You can read our Methodology and Data here.