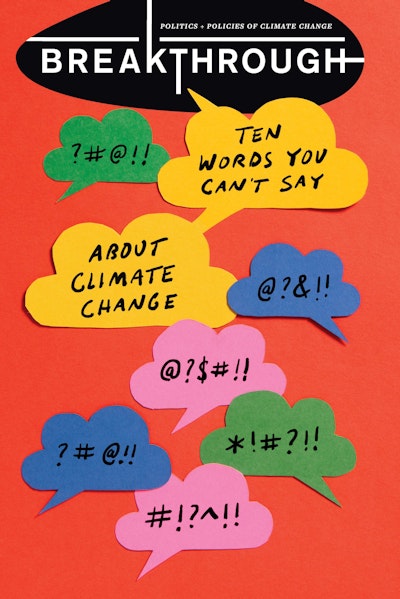

There Are No Villains in Climate Change

And narratives that tell us to blame “big oil” distract from the real work ahead

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

“Exxon knew about climate change half a century ago. They deceived the public, misled shareholders, and robbed humanity of a generation’s worth of time to reverse climate change.”

So reads the opening salvo of the “Exxon Knew” campaign—a project coordinated by a coalition of major environmental groups including 350.org, Greenpeace, and the Union of Concerned Scientists. Perhaps more than any other slogan or program, it captures the core political and tactical view of Western progressive environmentalists: Climate change is a problem caused by a particular villain—rapacious and conspiratorial corporations. Confronting, punishing, and shutting corporations down is the essential work of climate action.

The anti-corporate framing device is everywhere, including in coordinated public awareness campaigns, philanthropically supported lawsuits, and a veritable explosion of muckraking climate journalism and scholarship in recent years. Beyond Exxon Knew and extensive reporting by Inside Climate News, there is Bill McKibben’s column at The New Yorker, the DeSmogBlog, Emily Atkin’s weekly newsletter HEATED, Benjamin Franta’s fossil industry historiographies, the extended works of historians Naomi Oreskes and Geoffrey Supran, and much, much more.

The narrative at the heart of these projects is so ubiquitous as to seem compelling. It is also wrong. It misidentifies the cause of one of the central problems facing humanity and misdirects those seeking solutions towards a tempting, but ultimately counterproductive, target.

What Exxon knows

“Big Oil” is a convenient villain, especially for climate progressives. For one, corporations are already the default suspect for a left-wing coalition that elsewhere indicts Big Pharma, Big Ag, Big Tobacco, and on and on—conglomerates that, in anti-capitalist theory, are definitionally corrupt concentrations of wealth and power. Further, “Big Oil” is a way to sidestep the question of responsibility among the coalition’s own constituents. A single person’s gasoline consumption is trivial compared to the volumes of petroleum processed by a single large oil company (hence headlines like “Just 100 companies responsible for 71% of global emissions”).

And there is plenty of “evidence” against this story’s villain for those who want to look for it. Consider the sting operation conducted by Greenpeace in 2021. In that episode, Greenpeace operatives secretly recorded conversations with a lobbyist for ExxonMobil, in which he described the corporation’s strategies for opposing climate mitigation policies. An Exxon spokesperson has refuted the lobbyist’s claims. But to climate advocates, the whole episode confirmed what they had long asserted: Oil companies are the culprit behind the climate crisis, preventing climate action through nefarious intervention in the policymaking process.

Or take the ongoing reaction of climate hawks to the Biden administration’s economic policy, which credits environmental activists for any gains and faults the fossil fuel industry for any setbacks. Kate Aronoff, of The New Republic magazine, observed in summer of 2021 that “progressive political action committee Justice Democrats and the climate advocacy group Sunrise Movement are now calling the infrastructure package the #ExxonPlan.” (The package was ultimately signed into law and celebrated by the White House and congressional Democrats alike.) In reaction to Sen. Joe Manchin’s demonstrated reticence to support the Build Back Better Act, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez tweeted, “Manchin has weekly huddles w/ Exxon & is one of many senators who gives lobbyists their pen to write so-called ‘bipartisan’ fossil fuel bills.” (Manchin of course went on to write and pass the Inflation Reduction Act, which the Sierra Club called “the largest package of investments ever in clean energy, environmental justice, and climate action.”)

These are just a couple instances in which outcomes did not align with the critics’ claims. But even the general charge—that climate change is caused primarily by corrupt ultra-wealthy fossil energy corporations exercising undue influence to prevent policy from reducing society’s reliance on fossil fuels—falls apart after taking into account three totally uncontroversial facts.

First, the majority of fossil fuel resources are held and produced by governments, not corporations. Second, the overwhelming consumption of fossil fuels comes from low- and middle-income countries. And third, until recently, there were very few economically viable alternatives to fossil fuels.

If it were the case that private corporations produced, marketed, and sold all or even most fossil fuels around the world, one could make a plausible argument that such corporations are the primary source of most of our emissions. In that case, they would therefor be overwhelmingly responsible for climate change.

But it isn’t the case. Rather, 14 of the largest 20 oil and gas companies globally are government-controlled. Roughly 80% of global oil reserves and 60% of global natural gas reserves belong to governments or state-owned enterprises. And over half of current oil production comes from national oil companies. In other words, globally, fossil energy extraction is a socialized industry.

That’s not to say the extraction enterprise is a nice one. State-owned enterprises are often unresponsive to the democratic demands of their constituents. Authoritarian regimes, including so-called “petro-states” like Russia and Saudi Arabia, may use their hold on fossil resources for ill more than any big private conglomerate ever could. But democratically managed fossil energy also exists. From oil and gas production controlled by state-owned enterprises like Norway’s Equinor ASA, to Alaska’s extremely popular Permanent Fund, which is generated by oil and gas royalties, to the Navajo Nation’s attempts to maintain Indigenous coal production in the face of federal environmental regulation, examples abound.

The common denominator in all this “extractivism” is not fossil industry misinformation, concentration of resources and power, or corruption—it’s, quite simply, the abundance and usefulness of fossilized energy resources distributed throughout the Earth’s crust. And that points to another reason why Western progressives’ villainization of Big Oil doesn’t make much sense. According to one BP Statistical Review, in 2019, the OECD as a whole consumed 187 exajoules of fossil fuels, while countries outside the OECD consumed 302. Almost all of the growth of fossil energy consumption over the past generation has come from low- and middle-income countries, not wealthy ones—the nations where Big Oil supposedly rules.

The so-called “BRICS+” countries—upper-middle-income countries including Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Nigeria, Mexico, and Indonesia—are home to the majority of the world’s people (and also own nationalized oil and gas companies). In turn, most carbon emissions today are emitted in middle-income countries, not high-income ones.

A last nail in the coffin of the Big-Oil-as-villain story is that wherever they take hold, policies to replace fossil fuels are only as good as the technologies that can replace them. And until recently, most of the low-carbon alternatives commonly expected to displace fossil energy were radically expensive. Their cost has much less to do with Big Oil’s influence than with basic resource availability and engineering. Digging stuff up from the ground and burning it to produce heat and steam is a much older and simpler technology than splitting atoms, capturing solar photons in silicon, storing electric energy in lithium, fermenting nutritional proteins, engineering soil microbes to fix nitrogen, and the other constituent technological processes required for a low-carbon economy.

Today, electricity produced using wind turbines costs on average $50/MWh, which makes it competitive with coal- and gas-fired electricity at the margin. But in 1990, wind cost $200/MWh. And the cost of solar electricity was even more exorbitant. While solar’s average cost today is around $70/MWh, as recently as 2010 it was closer to $400/MWh. The obstacles facing nuclear power are as much the fault of regulatory sclerosis and environmentalist obstruction as economics, but it remains the case that building a nuclear plant today costs much, much more than building a natural gas plant. Aggressive penalties against fossil energy companies or consumption would not have changed this basic picture, which means that fossil fuels would still have been much cheaper.

And that’s just electricity, which accounts for less than a fifth of global carbon emissions. In the remaining sectors of the global economy, progress was not just difficult in the past—it’s difficult now, too. As a 2018 paper in Science demonstrated, the vast majority of global emissions come from activities and services for which there are no readily available low-carbon alternatives, like heavy aviation and shipping, industrial activities like fertilizer and cement production, agriculture, and land-use change.

It’s easy to blame corporations for the continuing prevalence of fossil fuels. But it is much harder to build an alternative.

ChatGPT HAS ENTERED THE CONVERSATION...

In environmentalist discussions, the term “villains” is often used to describe individuals, organizations, or corporations that are seen as responsible for environmental harm or as blocking progress on environmental issues. Environmentalists may use this term to describe those who engage in activities that damage the natural environment, such as polluting the air and water, destroying wildlife habitats, or causing climate change.

For example, an environmentalist might refer to oil companies as “villains” for their role in producing fossil fuels that contribute to climate change. Similarly, the term might be used to describe politicians who vote against environmental regulations or who deny the reality of climate change.

The use of the term “villains” is often meant to draw attention to the need for greater accountability and responsibility for environmental harm and to call for stronger action to protect the natural environment. It is also meant to inspire public activism and pressure on those seen as responsible for environmental harm, and to promote a more environmentally responsible and sustainable future.

It’s important to note that environmentalists believe in the importance of evidence-based decision-making and that the use of the term “villains” should be based on credible, peer-reviewed scientific evidence. Environmentalists also recognize the need for constructive dialogue and collaboration in addressing environmental problems, and believe that it’s important to work with all stakeholders, including corporations and governments, to create more sustainable and environmentally responsible solutions.

Why oil is still big

Challenges around invention, engineering, and infrastructure deployment were largely the problems of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Confronting humanity’s carbon emissions will look much like the planning, building, and maintaining of roads, railways, factories, sewer systems, and power lines that occurred, to a significant extent, before most of our parents were born. These endeavors were distinctly not the focus of the public interest movement and postwar New Left alliance from which institutional climate activism draws its lessons (and many of its leaders). From Ralph Nader’s war on the automobile industry, to Rachel Carson’s investigations into agri-chemicals, to the anti-smoking movement’s campaign against tobacco companies, the contemporary progressive agenda definitionally requires a corporate villain.

For climate activists and their counterparts in academia, this is not so much a conspiracy as a badge of honor. It turns out that the substantive and tactical foundations for this approach were explicitly strategized a decade ago.

In a 2012 workshop hosted by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), Harvard’s Naomi Oreskes and colleagues convened two dozen academics, advocates, and lawyers to identify lessons from the relatively recent anti-tobacco campaigns for climate activism. As the published summary from that gathering concluded, “There was widespread agreement among workshop participants that multiple, complementary strategies will be needed moving forward” that would combine “legal actions (for document procurement and accountability) with a narrative that creates public outrage.”

Prominent artifacts of this strategy include the “Exxon Knew” campaign; the Pulitzer-winning Inside Climate News investigations into the oil industry’s history of suppressing climate science research; and a series of lawsuits brought by citizen advocacy groups and state attorneys general to find oil and gas companies financially liable for economic damages caused by global climate change. (As of this writing, some of those lawsuits had been dismissed, while others are still working their way through the courts.)

There is nothing untoward about the La Jolla Conference or any of the downstream activities. Those attending the workshop did so openly and published their conclusions, including a discussion of disagreements among the participants. The United States’ free press, functioning court system, and a commitment to academic freedom make all of this more than fair game for activists and intellectuals alike.

But that doesn’t mean it hasn’t caused harm to environmentalists’ own cause. First, there’s the issue that, politically, their attempts to lay the blame squarely with the fossil fuel industry and Republican politicians did not prevent Americans from regularly electing Republicans or buying gasoline from Exxon.

Second, there is the complication that, just as Exxon and BP were supposedly asserting their powerful denialist claims in the 1990s and 2000s, emissions in the wealthy world did actually begin to plateau and decline—less out of consumer concern for the environment than because of technological change. That was the same time that emissions in China, India, and other emerging economies skyrocketed. There, fossil fuels helped lift billions out of poverty and the influence of private oil companies was barely present.

Third, as political economists Dominik Stecula and Erik Merkley have documented, messaging by the fossil fuel industries has had very little demonstrable impact on public opinion on climate change:

…there is relatively little evidence that this misinformation campaign directly reached or influenced the public in a meaningful way. The denialist media campaign peaked in the late 1990s and has been on the wane ever since. …The mainstream news media have generally been allies in disseminating mostly accurate—if too infrequent—information about scientific consensus and have rarely given space to contrarian analysts. Even the record in mainstream conservative outlets is much more mixed than the dominant narrative suggests.

As Stecula and Merkley write, “This organized and well-funded climate denial campaign may well have had an important influence on the actions of Republican office holders.” Less clear is what that influence bought the denialists in terms of demonstrable impact on fossil energy production or carbon emissions. And since climate change has become a matter of widespread public concern, the fossil fuel industry has adjusted.

For example, Exxon—the focus of activist campaigning—did support messaging and lobbying that cast doubt on the connection between carbon emissions and atmospheric warming in the 1990s. “The scientific evidence is inconclusive,” then-Exxon CEO Lee Raymond told the Detroit Economic Club in 1997, “as to whether human activities are having a significant effect on the global climate.” The company lobbied to emphasize uncertainty in scientific inquiries into climate change and funded denialist scientists and think tanks in the 1990s and early 2000s.

But the lion’s share of the company’s funding went not to marginal denialist outfits but to mainstream business organizations like the American Petroleum Institute, the American Enterprise Institute, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which did not question mainstream climate science. And more often than it supported denialism, the company acknowledged that the planet was warming, that anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions were a significant cause, and that continued warming could bring significant impacts to human societies.

Today, all the major oil companies are nominally in favor of climate policy, including policies to put a price on carbon emissions. In the early 2000s, British Petroleum renamed itself “BP” under the marketing slogan “Beyond Petroleum” and has become a reliable provider of energy consumption and production data across the energy technology portfolio. Additionally, Shell Oil has committed to reducing corporate emissions by 100% by 2050 and to spending as much as 25% of its budget on low-carbon technologies by 2025. The oil and gas industry at large is chiefly responsible for the decline of the other major fossil fuel, coal, thanks to its decades of investments in extracting natural gas from shale.

These commitments might ring hollow or appear to be greenwashing, and none of this is to say that technological innovation in low-carbon technologies could not have occurred earlier and faster. But the facts do complicate the notion that the fossil fuels industry has been engaged in a coordinated and powerful campaign of climate denial.

From conspiracy to progress

Given the lack of evidence for the villain story, the climate community has been left grasping at straws for evidence of corporate conspiracy. One is the idea that the very concept of personal ecological responsibility is fossil industry propaganda. In one recent paper, for example, Supran and Oreskes write:

A dominant public narrative about climate change is that “we are all to blame.” Another is that society must inevitably rely on fossil fuels for the foreseeable future. How did these become conventional wisdom? We show that one source of these arguments is fossil fuel industry propaganda.

According to Supran and Oreskes, and a growing consensus on the climate left, any discussion of personal environmental responsibility and carbon footprints bears the imprint of fossil industry propaganda and manipulation. Believe whatever you want about the value of personal environmental responsibility, but the theory itself can be traced back far beyond recent fossil industry messaging to foundational environmental texts including Aldo Leopold’s “A Sand County Almanac” and the “Whole Earth Catalog,” the “personal as political” ethos of postwar New Left politics, and the “leave no trace” environmental maxim still widely embraced by the outdoor advocacy community.

Another straw has been expanding the definition of “climate denial” to include all manner of ideological sins. Where once “climate denial” meant the literal rejection of mainstream climate science, the term has more recently been invoked against climate scientists who make less catastrophic conclusions out of rising emissions, politicians like Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, who weren’t opposed enough to the construction of the Keystone XL oil pipeline, and pro-nuclear environmentalists.

None of this has assured victory for the climate movement. Instead, it has led the movement toward fights that are at best internecine, and at worst wholly counterproductive. A movement that cannot decide whether personal behavior is important or not devotes endless energy to debating whether driving an electric vehicle or buying fake meat are virtuous endeavors. It works furiously to replace operating nuclear power plants with coal and gas plants and to strangle the advanced nuclear industry in its crib with miles of red tape, while looking past the horrifying human rights abuses in the solar supply chain, because the latter technology is “renewable” and the former is not. It throws itself on the gears of particular pipeline projects, neglecting that pipelines of some sort will be part of modern civilization forever, even if they carry hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and ammonia instead of oil and gas. It generates traffic-blocking and paint-throwing stunts that contribute nothing to the efforts to make low-carbon technologies scalable—and disenchant the broader public from the cause of environmental sustainability.

Climate change is simply a different kind of problem than the leaders of institutional climate activism want to fight, or that a modern progressive movement needs in order to justify its existence. In the age of industrial, fossil-fueled modernity, such a movement will not have a difficult time constructing narratives with nefarious-sounding actors and devious conspiracies to explain the broader environmental crisis. But these narratives are incidental, not central, to the goal of reducing carbon emissions and slowing global warming.

For all the reasons spelled out above, it would be a mistake to identify even a damning set of grievances against the fossil energy corporations as the primary cause of our collective climate challenge. The truth is much more complicated and, unfortunately, less amenable to political or social solutions than problems like smoking and marriage inequality proved to be.

Carbon is the keystone of the industrial world. The steam engine, the internal combustion and diesel engines, the Haber-Bosch process, and inherently fossil-intensive cement and steel production are the fundamental building blocks of modern society. Transitioning away from them is hard. Despite heightening concern about climate change and decades of progress on decarbonization, fossil fuels today still supply over 80% of global energy consumption. To this day, billions of people around the world live without sufficient modern energy, and fossil fuels remain necessary, if not comprehensively so, to address that enduring energy poverty.

Creating a new world in which comfort, security, freedom, and prosperity are possible with low-carbon technologies and infrastructure is the gargantuan task humanity faces this century. Fossil fuel companies will sometimes adapt and contribute, perhaps especially in the fields of alternative liquid fuels, carbon dioxide pipelines, and other technical and infrastructural endeavors at which they already excel. They will sometimes suffer and collapse, as has the American coal industry, which now stumbles toward its grave thanks largely to cheap natural gas and renewable energy technologies. And they will sometimes try to obstruct policy and technological progress—actions that should be uncovered, condemned, and punished.

As such, there will always be a role for muckraking environmental journalists, public interest litigators, and scholarly criticism of the fossil fuel industry. But even if we villainized, taxed, or litigated the fossil fuel companies out of existence, that would not address the majority of global emissions that governments, not industry, are responsible for, nor would it magic into existence the low-carbon electric power generation, transportation and aviation, industrial, and agricultural technologies necessary to enable modern existence without carbon emissions. That doesn’t mean, however, that the industry should not be regulated, taxed, or litigated against. In many contexts, they certainly should be.

But effectively addressing climate change requires an understanding of what causes it in the first place. If we focus myopically on any one bad guy, we are sure to fail.