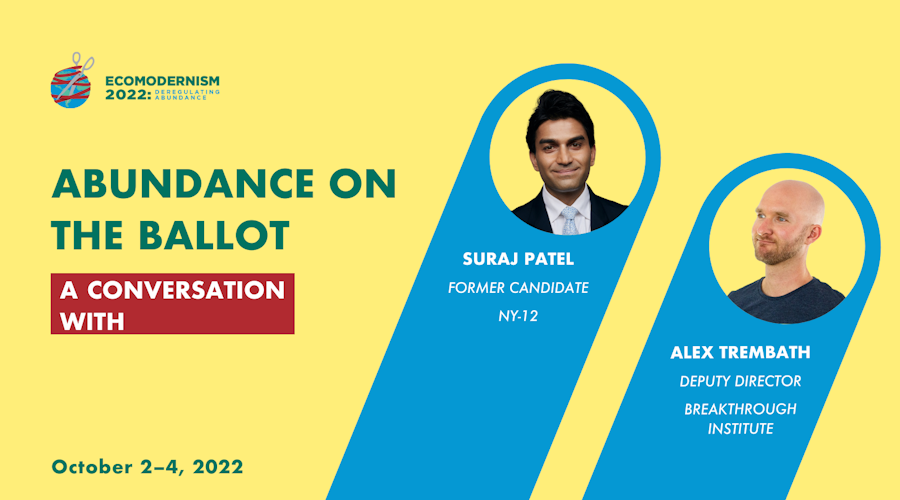

Ecomodernism 2022: Deregulating Abundance

Ecomodernism 2022: Deregulating Abundance

The material abundance that characterized 20th century American infrastructural and economic development came with major downsides.

Industrial food systems—awash in irradiated seed varieties, irrigated water, and synthetic nitrogen fertilizers—eliminated starvation for the first time in human history, but in doing so denuded forests and grasslands, leached hypoxic nitrogen runoff, and otherwise polluted the nation’s air and waterways. Continent-spanning pipes, wires, and highways allowed for the transmission of energy, goods, and people, but dissected ecosystems and neighborhoods in the process, generating extensive industrial pollution and, of course, greenhouse gas emissions. New technologies abounded, but with them came fears of previously unimaginable risks – invisible radiation from nuclear technologies, genetic drift from bioengineered crops.

The postwar regulatory state was erected, largely, to mitigate these downsides. The Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, and bureaucracies like the Environmental Protection Agency, the Food and Drug Administration, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission were created to monitor, regulate, and–often explicitly–to restrict the deployment of new infrastructure and novel technologies.

These new policies and agencies had salutary public health and environmental effects. Conventional pollution has plummeted in the 50 years since the EPA was created. Food contamination is rare. Occupational accidents and deaths from natural disasters are down. Even greenhouse gas emissions, which have never been formally regulated in the United States, have declined markedly, partially thanks to regulations against co-pollutants like particulates and sulfur oxides that are common in fossil energy combustion.

But effectively addressing climate change will require more than pruning our techno-economic systems at the margins. Instead, it will require grafting a wholly new abundance on top of the old one. And the innovation, construction, and socialization of that new abundance are in many ways being choked off by the same administrative state designed to reign in the worst excesses of the old abundance.

That the environmental challenges of the 21st century differ so much from those of the 20th century is a truth not yet universally acknowledged by the mainstream environmental movement, who owe so much to the institutions and figureheads of prior generations. The legacy organizations of conventional environmentalism may simply be incapable of assimilating a deregulatory agenda into their priorities and their culture. Yet a deregulatory environmentalism is precisely what the so-called “abundance agenda” calls for.

We may require a new set of rules and institutions to realize that agenda. And that might not only mean new environmental organizations–or, dare we say, ecomodernist ones–but also a new politics.

A decade ago, the so-called “all-of-the-above” approach to energy policy—one that embraced public policy and investment supportive of both low-carbon energy and fossil fuels—was the norm. Renewables were much more expensive than they are today, climate change was ranked relatively lower on policymakers’ list of priorities, and, not incidentally, the approach was working: the shale gas revolution that began in earnest around 2009 was lowering energy costs, creating hundreds of thousands of jobs, and driving some of the steepest emissions reductions in the world. Today, with cheaper renewables, amidst more prominent catastrophist sentiment around climate risk, and farther along the coal-to-gas bridge, one might think the usefulness of this approach had come to an end. And yet, as revealed by the recently advanced Inflation Reduction Act and the Biden Administration’s backsliding on fossil energy restrictions, “all-of-the-above” is still the modus operandi in Washington. What should we make of this? Are policymakers wise, or short-sighted, to sustain investments in oil and gas supplies amidst spiking inflation and energy prices? Can the “all-of-the-above” approach to energy abundance build support for long-term decarbonization, or does such an approach inescapably kick the can down the road?

The burgeoning urbanist movement has argued forcefully that YIMBY, or “yes in my backyard,” is not just a housing affordability agenda but a climate agenda. Denser, cheaper housing enables more people to occupy less land, making more efficient use of infrastructure and supply chains while reducing pollution associated with commuting and allowing greater access to public transit. At times, the YIMBY movement veers into active antipathy towards suburbs, exurbs, and personal vehicles. Is this the inevitable equilibrium for pro-housing, pro-transit advocacy? Might it be the case that some people will prefer cars and suburbs even in a future where exclusionary zoning is abolished? And could the YIMBY movement even take root in the suburbs, away from the dense, housing-starved corridors it thrives in today?

Pulling Up the Ladder

For all the talk about the need for an abundance agenda in the United States, it is all too easy to forget the relative abundance we already enjoy in rich countries, and the lack of anything comparable in low- and middle-income economies. Worse still, building industrial, abundant energy and agricultural infrastructure in poor countries is increasingly stifled by constraints imposed by trade and development finance policies in the United States and Western Europe. This has been called “pulling up the ladder,” an apt metaphor to describe limiting investment in fossil fuels, industrial agriculture, hydroelectric and nuclear power, and other technologies taken for granted in the wealthy world but largely out of reach for poorer countries. This panel will describe a number of ways such restrictions constrain development and growth abroad, how authoritarian regimes take advantage of the situation, and what more equitable and abundance-oriented international policy would look like.

Time to Build

As the nation’s halting attempts to build high-speed rail, nuclear power plants, high-voltage transmission lines, and solar and wind farms reveal, the obstacles to decarbonization stem less from the availability of low-carbon technology than from the capacity for siting, permitting, and building the necessary infrastructure. High-level proposals to address this problem have come from “supply-side progressivism,” “state-capacity libertarianism,” neoliberalism, and beyond. This panel will feature a variety of ideological perspectives on the policy and coalitional imperatives to be sorted out before any such supply-side agenda can be effectively pursued.