How Much Does Big Oil Owe Californians for the LA Fires?

Climate 'Superfund' Laws Won't Cover the Costs of Climate Resilience

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

Last year, both New York and Vermont passed “climate Superfund” laws that impose financial liabilities on large carbon emitters for the damages caused by extreme weather and other climate impacts. California lawmakers introduced similar legislation last year, and are widely expected to do so again in the wake of Southern California’s recent devastating fires—the most expensive natural disasters in American history. With an estimated $250 billion in economic damages and about 30 confirmed deaths caused by the fires, there will likely be significant political support for a law like this.

So how much would large carbon emitters owe Californians if the bill becomes law?

The legislative text allows one year for the California Environmental Protection Agency to conduct a “climate cost study” determining the total amount of climate damages owed by each large emitter, defined as institutions that are “responsible for more than 1,000,000,000 metric tons of covered fossil fuel emissions, as defined, in aggregate, globally during the covered period” of 2000-2020.

According to data collected by the UK nonprofit group InfluenceMap, there are 86 eligible entities, but most of them operate outside the United States. For the purposes of this exercise we confined our analysis to the 19 eligible entities headquartered in America:

If the bill becomes law, these large emitters collectively would be, hypothetically, liable for 0.2% of the damages from the LA fires, or just under $495.27 million.

This calculation assumes that the fires were about 6% worse due to climate change effects, which is in line with a calculation on fire intensity (using the methods from Brown et al. 2025) as well as a recent calculation on the Fire Weather Index (from World Weather Attribution). It also assumes that large emitters' relative contribution to that 6% increased risk is proportional to their cumulative emissions over 2000-2020 as defined by the legislation (about 73.3 gigatons CO2) divided by all cumulative anthropogenic emissions since 1850 (about 2220 gigatons CO2).

That's certainly not a trivial amount of money, of course. And individual emitters would be saddled with large absolute financial liabilities. ExxonMobil, for instance, would be on the hook for approximately $91.35 million according to this analysis, or about .04% of the total damages from the LA fires. But these figures are small compared to both the total estimated cost of the fires and ExxonMobil’s market capitalization ($463.6 billion).

Of course, large emitters like ExxonMobil would prefer not to pay damages associated with their historic emissions, even if those damages in the event of any individual extreme weather event are modest compared to their total financial assets. A hundred million here and a hundred million there would start to add up, even for a massive conglomerate.

And lacking an unambiguous legal definition or precedent for financial climate liabilities, it’s overwhelmingly likely that claims under these climate Superfund laws will be challenged in the courts and probably adjudicated for years. Dozens of parties have already filed suits against the Vermont and New York laws. Where exactly the US judicial system ultimately falls on the validity, practicality, and constitutionality of these varied state bills is of course hard to predict with much confidence.

The upshot of it all, though, is that even under strict adherence to the letter of these laws, almost all of the costs of natural disasters will continue to be borne by the people affected, local governments, and the insurance and reinsurance markets, not the fossil fuel industries. And that’s because anthropogenic climate change simply remains a minor contributing factor in the frequency, intensity, and cost of natural disasters. The natural stochastic indifference of the Earth’s climate to human well-being remains the driving force behind all extreme weather, and the exposure of people and infrastructure remains the overwhelming determinant of disaster costs and impacts.

The math is pretty unforgiving here. Even if public administrators chose to allocate 100% of the risk behind natural disasters to large emitters, those aggregate liabilities would still only cover a few percentage points of the overall costs of the disasters. And that’s because even large emitters’ cumulative impact on carbon budgets over a twenty year period are a drop in the bucket compared to global historic cumulative emissions, which of course is the only way to quantify the driving force behind increased anthropogenic climate risk.

Even under extremely permissive assumptions about climate risk and legal liability, there are other inextricable factors that make it difficult to put a hard number on an individual emitters’ financial culpability. The LA fires, for instance, were so expensive largely because they occurred in one of the wealthiest real estate markets in the world. Much larger Western wildfires yielded far lower total economic costs simply because they occurred in poorer and more remote areas. Just compare the recent fires to the 2018 Camp Fire in California, which burned about 150,000 acres, resulting in about $16.5 billion in economic costs and the death of 85 people. That amounts to an area five times larger than the recent Los Angeles fires, with about three times the body count, and yet less than one-tenth the estimated economic cost. The exposed wealth and infrastructure that lead to such large economic losses also saves lives.

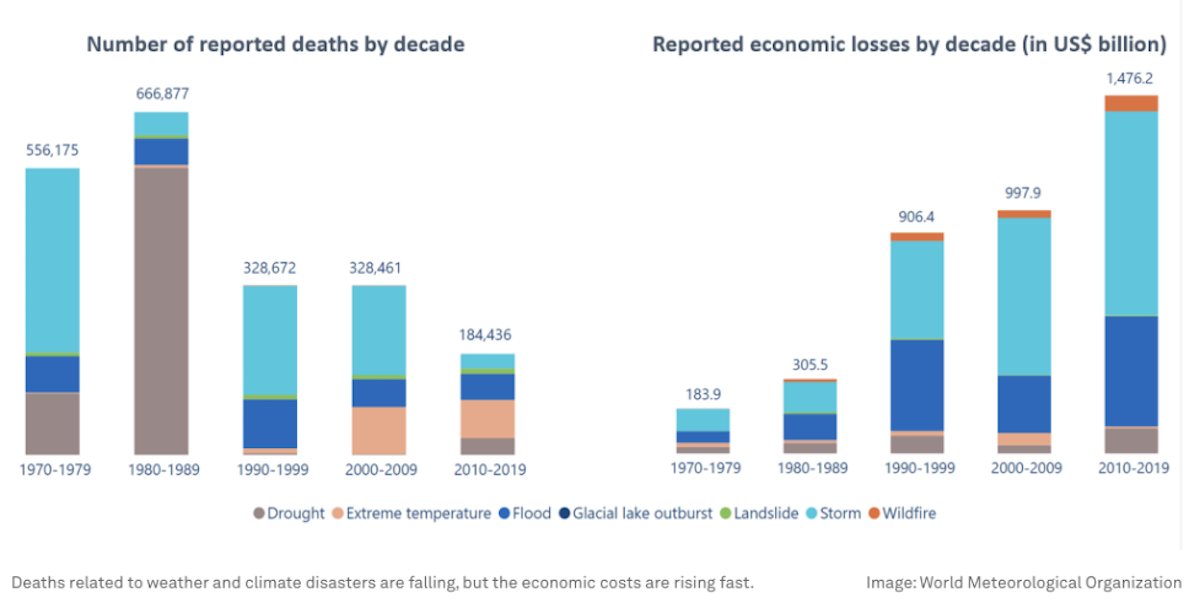

This inverse relationship, between economic cost and human mortality, is a consistent feature of dangerous weather and disasters, as these data from the World Meteorological Organization clearly show:

And all that protective wealth and infrastructure, at the end of the day, continues to rely on fossil-fueled economic activity, energy, locomotion, concrete, cement, steel, plastic, fertilizer, and much more. The reality is that fossil fuel emissions are empirically, if marginally, increasing the risk associated with some forms of extreme weather while still undergirding the modern industrial systems that allow for human societies to protect themselves from extreme weather.

The conventional method for determining net economic climate impacts has been to estimate the aggregate, discounted costs and benefits of fossil fuel exploitation, establish a general consensus on the net “social cost of carbon,” and levy that cost on emitters through a tax or cap-and-trade system.

But after the successive failures to pass a meaningful legislative carbon price in the United States and beyond, climate advocates decided to give up and attack fossil fuel industries in the court of public opinion as well as in the literal courts. Liability lawsuits and laws like these would purportedly avoid the “regressive” nature of a carbon tax, which the Sunrise Movement now calls “the fossil fuel industry’s preferred climate ‘solution.’” But it’s far from obvious why legal financial liability under the “polluter pays” principle, as opposed to the market-oriented approach epitomized by a carbon tax, would prevent the affected corporations from passing their increased costs onto consumers of fossil fuel products.

So while Big Fossil will surely fight tooth and nail against both private lawsuits and new liability laws, even if they fail, we can be sure where those new financial liabilities will ultimately land: on consumers’ gas prices and electric utility rates.

There is merit to the idea of internalizing the economic externalities created by carbon emissions. But to conclude that the conventional and straightforward method for doing so—a carbon tax—is regressive, and then try to force a Rube-Goldberg financial liability through the courts and executive agencies, is difficult to defend both intellectually and practically.

The fact of the matter is that policy penalties on fossil fuel corporations will play a minor role at most in either accelerating decarbonization or financing societal resilience to extreme weather. Moreover, while there may be worthwhile climate adaptations that could be funded through excise taxes, these state-level “climate Superfund” bills are constitutionally questionable ways to do so. And even if fossil fuel corporations do ultimately face durable legal liabilities for the impacts of their legacy emissions, these liabilities will pale in comparison to the total costs human societies suffer at the hands of both climate change and the climate itself.