Absolute Decoupling of Economic Growth and Emissions in 32 Countries

-

-

Share

-

Share via Twitter -

Share via Facebook -

Share via Email

-

The past 30 years have seen immense progress in improving the quality of life for much of humanity. Extreme poverty — the number of people living on less than $1.90 per day — has fallen by nearly two-thirds, from 1.9 billion to around 650 million. Life expectancy has risen in most of the world, along with literacy and access to education, while infant mortality has fallen. Despite perceptions to the contrary, the average person born today is likely to have access to more opportunities and have a better quality of life than at any other point in human history. Much of this increase in human wellbeing has been propelled by rapid economic growth driven largely by state-led industrial policy, particularly in poor-to-middle income countries.

However, this growth has come at a cost: between 1990 and 2019, global emissions of CO2 increased by 56%. Historically, economic growth has been closely linked to increased energy consumption — and increased CO2 emissions in particular — leading some to argue that a more prosperous world is one that necessarily has more impacts on our natural environment and climate. There is a lively academic debate about our ability to “absolutely decouple” emissions and growth — that is, the extent to which the adoption of clean energy technology can allow emissions to decline while economic growth continues.

Over the past 15 years, however, something has begun to change. Rather than a 21st century dominated by coal that energy modelers foresaw, global coal use peaked in 2013 and is now in structural decline. We have succeeded in making clean energy cheap, with solar power and battery storage costs falling 10-fold since 2009. The world produced more electricity from clean energy — solar, wind, hydro, and nuclear — than from coal over the past two years. And, according to some major oil companies, peak oil is upon us — not because we have run out of cheap oil to produce, but because demand is falling and companies expect further decline as consumers increasingly shift to electric vehicles.

The world has long been experiencing a relative decoupling between economic growth and CO2 emissions, with the emissions per unit of GDP falling for the past 60 years. This is the case even in countries like India and China that have been undergoing rapid economic growth. But relative decoupling alone is inadequate in a world where global CO2 emissions need to peak and decline in the next decade to give us any chance at limiting warming to well below 2℃, in line with Paris Agreement targets.

Thankfully, there is increasing evidence that the world is on track to absolutely decouple CO2 emissions and economic growth — with global CO2 emissions potentially having peaked in 2019 and unlikely to increase substantially in the coming decade. While an emissions peak is just the first and easiest step towards eventually reaching the net-zero emissions required to stop the world from continuing to warm, it demonstrates that linkages between emissions and economic activity are not an immutable law, but rather simply a result of our current means of energy production.

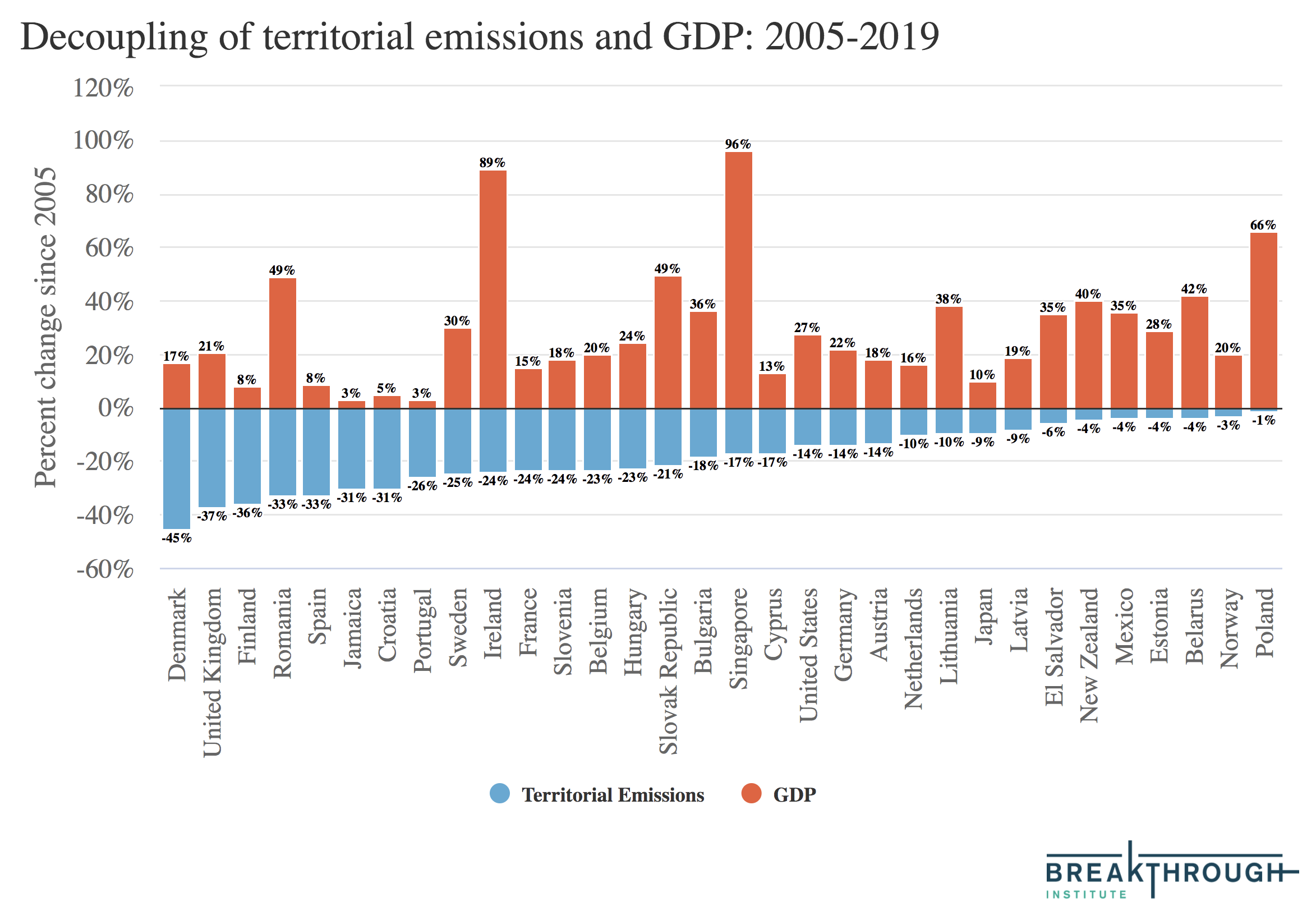

In recent years we have seen more and more examples of absolute decoupling — economic growth accompanied by falling CO2 emissions. Since 2005, 32 countries with a population of at least one million people have absolutely decoupled emissions from economic growth, both for terrestrial emissions (those within national borders) and consumption emissions (emissions embodied in the goods consumed in a country). This includes the United States, Japan, Mexico, Germany, United Kingdom, France, Spain, Poland, Romania, Netherlands, Belgium, Portugal, Sweden, Hungary, Belarus, Austria, Bulgaria, El Salvador, Singapore, Denmark, Finland, Slovakia, Norway, Ireland, New Zealand, Croatia, Jamaica, Lithuania, Slovenia, Latvia, Estonia, and Cyprus. Figure 1, below, shows the declines in territorial emissions (blue) and increases in GDP (red).

To qualify as having experienced absolute decoupling, we require countries included in this analysis to pass four separate filters: a population of at least one million (to focus the analysis on more representative cases), declining territorial emissions over the 2005-2019 period (based on a linear regression), declining consumption emissions, and increasing real GDP (on a purchasing power parity basis, using constant 2017 international $USD). We chose not to include 2020 in this analysis because it is not particularly representative of longer-term trends, and consumption and territorial emissions estimates are not yet available for many countries.

There is a wide range of rates of economic growth between 2005-2019 among countries experiencing absolute decoupling. Somewhat counterintuitively, there is no significant relationship between the rate of economic growth and the magnitude of emissions reductions within the group. While it is unlikely that there is not at least some linkage between the two factors, there are plenty of examples of countries (e.g., Singapore, Romania, and Ireland) experiencing both extremely rapid economic growth and large reductions in CO2 emissions.

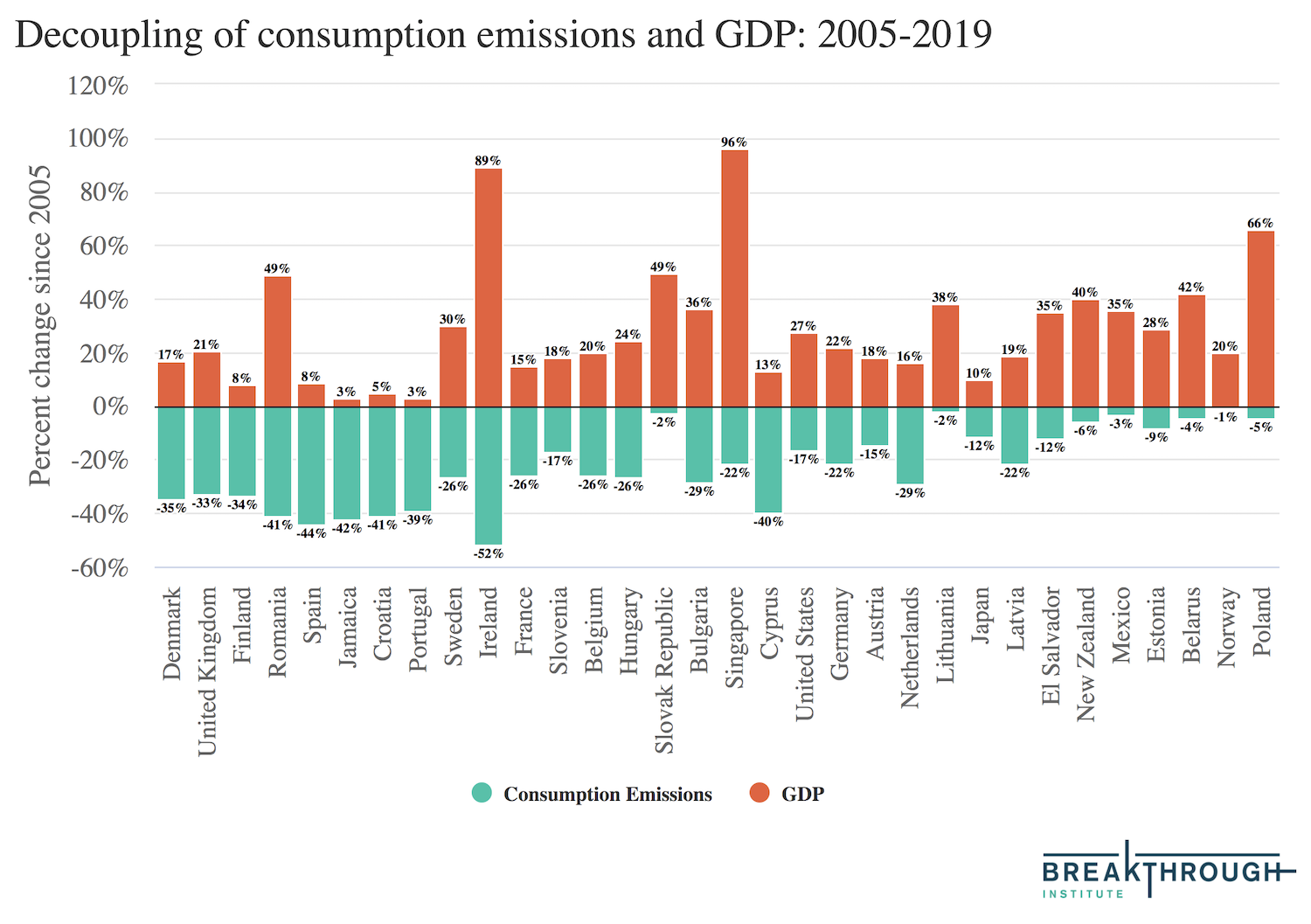

One of the primary criticisms of some prior analyses of absolute decoupling is that they ignore leakage. Specifically, the offshoring of manufacturing from high-income countries over the past three decades to countries like China has led to “illusory” drops in emissions, where the emissions associated with high-income country consumption are simply shipped overseas and no longer show up in territorial emissions accounting. There is some truth in this critique, as there was a large increase in emissions embodied in imports from developing countries between 1990 and 2005. After 2005, however, structural changes in China and a growing domestic market led to a reversal of these trends; the amount of emissions “exported” from developed countries to developing countries has actually declined over the past 15 years.

This means that, for many countries, both territorial emissions and consumption emissions (which include any emissions “exported” to other countries) have jointly declined. In fact, on average, consumption emissions have been declining slightly faster than territorial emissions since 2005 in the 32 countries we identify as experiencing absolute decoupling. Figure 2, below, shows the change in consumption emissions (teal) and GDP (red) between 2005 and 2019.

There is a pretty wide variation in the extent to which these countries have reduced their territorial and consumption emissions since 2005. Some countries — such as the UK, Denmark, Finland, and Singapore – have seen territorial emissions fall faster than consumption emissions, while the US, Japan, Germany, and Spain (among others) have seen consumption emissions fall faster. Figure 3 shows reductions in consumption and territorial emissions for each country, with the size of the dot representing the size of the population in 2019.

Absolute decoupling is possible. There is no physical law requiring economic growth — and broader increases in human wellbeing — to necessarily be linked to CO2 emissions. All of the services that we rely on today that emit fossil fuels — electricity, transportation, heating, food — can in principle be replaced by near-zero carbon alternatives, though these are more mature in some sectors (electricity, transportation, buildings) than in others (industrial processes, agriculture).

This is not to say that infinite economic growth is desirable (or even possible), particularly given that the global population is expected to start to shrink by the end of the 21st century (and well before that in most currently wealthy countries). There will be some tradeoffs between economic growth and climate mitigation — particularly if the world is to meet ambitious mitigation targets. But it is possible to envision a world that is prosperous, equal, and at net-zero emissions; indeed, all of the future emissions scenarios used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) do just that.

It is also useful to look at a few specific cases of larger countries that have absolutely decoupled emissions and GDP over the past 15 years.

Emissions reductions in the US have been a result of a wide variety of factors; this includes the switch from coal generation to lower-carbon natural gas, the rapid expansion of wind and solar generation, reduced industrial energy consumption, reduced electricity use in buildings, and reductions in transportation emissions — particularly as a result of increased vehicle fuel economy and reduced miles driven per-capita. Since 2005, US territorial emissions have fallen around 15%, with consumption emissions falling around 18% (much larger reductions were seen in 2020, and some of this is expected to persist). At the same time, GDP has increased by around 29%.

In the UK, territorial emissions have fallen by nearly 40% and consumption emissions have fallen by around 30%, while GDP has increased by 22%. Similar to the US, there are a wide variety of drivers of UK emissions reductions, though renewable energy generation, reductions in electricity use, and reductions in industrial and residential energy use are the largest contributors.

In Germany, territorial emissions have fallen around 15%, and consumption emissions have fallen by around 20%, while GDP has increased by 24%.

In France, territorial emissions have fallen by around 25%, and consumption emissions have fallen by a similar amount, while GDP has increased by 16%. It is a bit notable that France has seen larger emission reductions — as a percentage of total emissions — than Germany over this period, likely due in part to Germany’s choice to prioritize shutting down nuclear power plants over coal ones.

The Japanese emissions trajectory has been a bit more variable since 2005 than the prior countries we have examined, decreasing during the financial crisis, rebounding during the recovery and in the aftermath of the Fukushima disaster as a sizable portion of its clean electricity generation was shut down, before decreasing in more recent years. Over the full period, territorial emissions have fallen by a bit over 10%, while consumption emissions have fallen by around 13%.

These 32 countries show that it is possible to have economic growth at the same time that CO2 emissions decline, even accounting for embodied emissions in goods imported from overseas. However, these are mostly relatively wealthy countries whose economies tend to be increasingly driven by lower-energy information technology and service sectors. We have relatively few examples of low- or middle-income countries with a focus on energy-intensive manufacturing experiencing absolute decoupling to date.

That said, with the rapid cost reductions of clean energy and an expected peak in Chinese emissions in the next five to ten years, it is only a matter of time before absolute decoupling becomes the norm. The extent to which this will occur rapidly enough to avoid dangerous levels of warming depends on both the degree of technological progress and the willingness of governments worldwide to invest in mitigating climate change.