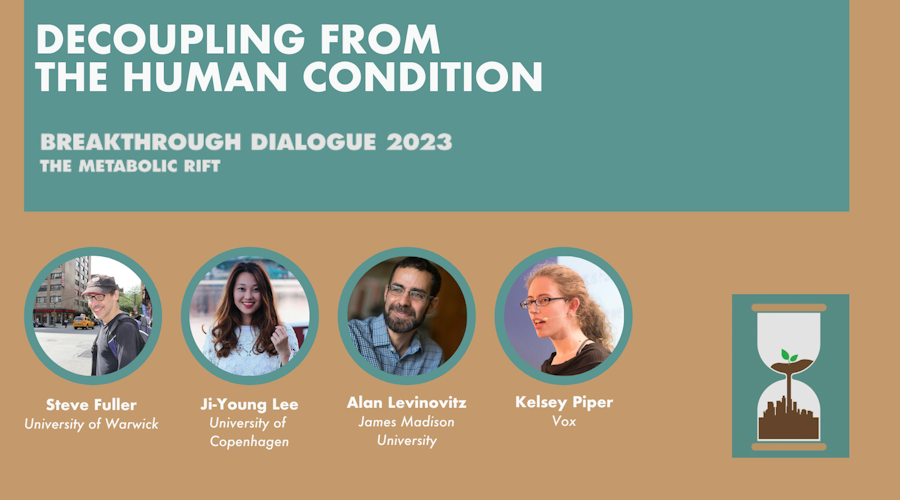

2023 San Francisco Dialogue: The Metabolic Rift

Breakthrough Dialogue 2023: The Metabolic Rift

It is not a stretch to suggest that two biogeochemical transformations have underpinned all of global modernity - the movement of enormous amounts of fossilized carbon from the terrestrial Earth into the atmosphere and enormous amounts of nitrogen from the Earth’s atmosphere into terrestrial environments.

Industrialization required the use of power at levels far beyond that which animal metabolism could provide and in locations distant from easily captured wind and water power. Urbanization concentrated large populations in numbers that could not be fed locally and from which nutrients could not be easily returned to the sites of food production. Only with fossil fuels and industrial fertilizers were such social and economic transformations possible.

Fuel and fertilizer decoupled the provision of food, energy, and materials from the biomass based economy, liberating human societies from the malthusian limits that had theretofore constrained both the size of human populations and the material conditions in which they could live and allowing for extraordinary improvements to living standards and flourishing of both individual and collective human possibilities over the last 150 years.

The notion of the metabolic rift owes its provenance to Marx, who described a disruption in the “metabolic interaction between man and the Earth.” But it speaks to foundational questions about humans and the earth that are arguably more contested today than they were in Marx’s time. Can high energy societies of billions be sustained? Can we survive the loss of biodiversity and build up of waste and pollution that industrial modernity has wrought? Does the human future depend upon maintaining fragile ecosystems or robust human capabilities to remake our environments?

That none of these debates can actually be resolved prospectively speaks to broader questions still. Are humans masters of the Earth or servants, fundamentally Earthbound beings or capable of transcending the limits of Earthly chemistry, biology, and physics? Must we colonize other worlds to assure the survival of the species? Might we transform ourselves, our anatomy, biology, and cognition into higher, perhaps eternal forms? Are we already doing so or do such claims reflect a denial of the fundamental human condition?

The edge cases frame the underlying political and philosophical commitments, how we orient ourselves towards change, uncertainty, human nature and human possibility. To celebrate the metabolic rift is to believe in material abundance as a normative end, a practical possibility, and a necessary precondition for humans to reach their full potential. To condemn it is to believe that the human spirit can only be authentically expressed when it is grounded, constrained, and tied to the Earth. In this Breakthrough Dialogue we explore the outer edge of these debates in order to sharpen our thinking about the central arguments and use the reductive and ad absurdum to help us think about how to navigate the emergent complexity that is the human present and future.

In writing about the increasingly intensive use of mined and imported guano fertilizer, Karl Marx described a rift in the “metabolic interaction between man and the Earth.” Ecomodernists readily recognize this as an anticipation of our modern understanding of ecological decoupling, while other scholars have retconned modern Western environmentalist metaphysics onto the Marxist project. Marx, of course, is not here. But we are. What are we to make of this rift? How does humanity’s loosening entanglement with Earth’s metabolism align with the type of societies we imagine ourselves building, whether ones built on regenerative and nature-based practices, highly urbanized industrial ones, or an interwoven mixture of approaches? Does industrial “extractivism” alienate human societies from a more sustainable and satisfying harmony with nature?

Even ancient cultures understood there was something especially distant, even otherworldly, about the stars. Today, though it has never felt more feasible, space exploration might still represent a rift too far. Must humans colonize the galaxy to ensure the long-term survival of our species? Is that even practically possible, given the immense thermodynamic demands of Earth’s gravity well and the degree to which we evolved into creatures of this planet, and no others? Is the Earth itself the one truly non-negotiable planetary boundary, our adaptedness to Earth systems the hard limit on our potential as explorers? How we answer these questions necessarily informs our understanding of society’s ability to adapt to physical danger, and humans’ ability to alter our own nature to explore the future.

The classic ecomodernist examples of decoupling are technologies that have reduced human dependence on the natural world. Modern energy technologies displace bioenergy; intensive farms allow us to grow more food on less land; dense settlements reduce the total footprint of humanity on wild nature. But has technology also decoupled us from the natural human condition? Antibiotics, vaccines, in-vitro fertilization, organ transplantation, cosmetic and prosthetic surgeries, SSRIs, and even the Internet—to name just a sampling—have already extended and expanded our physiological reality far beyond what our ancestors experienced. Looking into the future, humans must reckon with the implications of dramatic life extension therapies, artificial womb technologies, targeted CRISPR-based hacking of our genetic code, cognition merged with artificial intelligence, and much more. What will we learn about our species, our moral frameworks, and our relationship to the “natural” world, whatever that will come to mean?

In decoupling human well-being from destruction of nature, do human societies become less vulnerable to the vagaries of the natural world? How far can that relationship be pushed? Ecomodernists have long debated whether technology will allow humans to transcend planetary boundaries, or simply to thrive within them. In this panel, we return to that debate. What does modern Earth science tell us about biophysical constraints in Earth systems? How does their presence, and the threat of breaching them, inform humanity’s efforts to innovate and build just, abundant societies?

Most of the vertebrate animals on the Earth’s surface today were domesticated by humans, as livestock, companions, or both. Of what we call “wild” animal life, some provide putative ecosystem services, like the ducks that fertilize the wetlands that prevent coastal erosion. Still others offer less that could defensibly be called economic value but, arguably, have “intrinsic” or “existence” value for human societies, such as the tigers in Rajasthan or the grizzly bears in Yellowstone. What duties do we have towards cats and cows, squirrels and sparrows, walruses and wolverines? How do, and how should, we discern their interests? Do animals play an essential role in mediating our relationship with nature, or do they deserve a kind of citizenship with agency independent of our own? And as we celebrate the animal life in protected habitats and wilderness areas, do we not also inherit the moral responsibility for the animals suffering in those places?

The alleged paradox of climate change is that economic damages have risen while mortality from climate impacts has declined. Of course the paradox is easily solved: modern societies put more wealth and infrastructure “in harm’s way,” and that same wealth and infrastructure protect humans from the vagaries of Earth’s climate. We have, to a significant degree, walled our cities, farms, and transit systems off from the vagaries of nature. But how strong are the walls? Do future climate risks, like wildfires on a hotter and drier planet or hurricanes hitting coastlines with climbing sea levels, pose fundamentally different threats than humans have encountered historically?

Human societies have improved food security and made agriculture more sustainable through innovations in mechanization, fertilization, irrigation, and more. But they have also done so by innovating in the food products themselves. For centuries, farmers and ranchers have bred crops and livestock to make them more appealing, resilient, and productive. Today, farmers and scientists are using CRISPR, cell-cultured proteins, value-chain innovation, and other techniques and practices to design the food systems of the future. This panel will showcase some of the cutting-edge innovations taking place in the food-tech space.